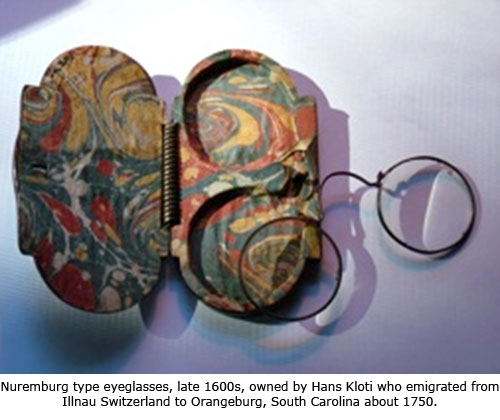

As bizarre as it sounds, the earliest eyeglasses-dating to the Middle Ages – were designed without temple pieces. Instead, the wearer – or, more aptly, holder – had to dangle the glasses (shaped like a scissors handle) in front of his or her face.

The question of how to make eyeglasses more functionally sound puzzled designers and engineers for some time, with most solutions involving somehow tying glasses to an individual's head. It wasn't until the 1700s – nearly 500 years after the invention of eyeglasses – that a British optician named Edward Scarlett invented temple pieces, thus perfecting the design of eyeglasses for the ages – or so it seemed.

|

During the American Civil War, the optical world faced a problem: Military blockades meant an end to the import of foreign made spectacles, while metal rationing on either side of the conflict meant that American opticians had little to use for making their own glasse – and that the products they could produce would be even more expensive than usual. Unpredictably, a solution arose in the form of an unpopular style of French eyeglasses called the pince-nez (literally "pinch nose"), which lacked temple pieces and were secured to the wearer's nose through a variety of means. Seizing upon this design, American optician John Jacob Bausch (half of the founding team of Basuch and Lomb) began marketing his own style of pince-nez, crafted out of vulcanized rubber. Quickly, the glasses – easier and cheaper to manufacture than metal glasses with temples – became a runaway sensation for the duration of the war.

|

With the end of the Civil War and a return to relative normalcy for the United States, pince-nez may have slipped into obscurity as a wartime phenomenon if not for the negative connotations of eyeglasses and the vanity of their wearers. In late 18th century America, most eyeglass wearers were presbyopes, and literacy was still at its highest among leaders of religious groups. This led to the stereotype that eyeglass wearers were elderly clergymen, an image directly opposed to the ideal of the young, strapping frontiersman-taking shape in the American imagination.

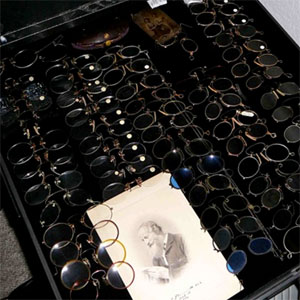

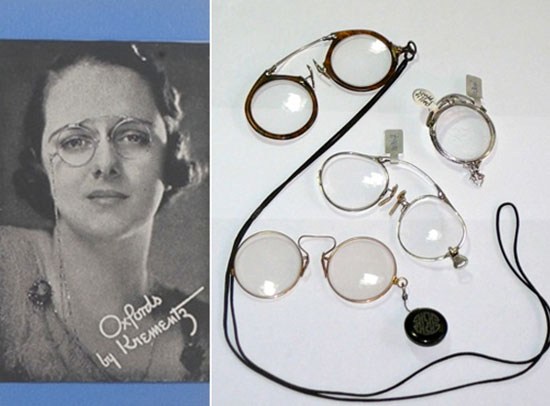

Thus, the pince-nez became the ideal piece of eyewear for individuals who wanted to downplay their need for glasses; and, as with many other trends, this was quickly caught upon by the wealthy, who turned pince-nez into a status symbol by having pairs custom-crafted to fit their noses in such materials as gold and silver. Although glasses with temples remained in production, pince-nez became the defining piece of eyewear at the turn of the century.

Technology must remain functional in order to stay relevant, though, and while pince-nez satisfied wearer's vanities, they could not satisfy the desire for a practical piece of eyewear. Advances in optometry in the early 1900s led to a rise in the diagnosis of myopia – and with it, astigmatism. While pince-nez could be attached to the nose, they could not be attached securely, and the constantly shifting nature of the lenses rendered them largely unfeasible.

Though solutions were offered – such as a spring apparatus that was meant to hold the glasses more firmly in place – pince-nez began to fade from popularity in the early part of the 1900s as the maligned temple was rediscovered. Ironically, while pince-nez retained a few aficionados, the style became synonymous with being elderly and out of touch – two of the very associations their first wearers had sought to avoid. By the 1940s, pince-nez were almost exclusively available through Shuron Optical, which filled about 200 orders a month to satisfy demand from elderly wearers.

Despite passing from popular consciousness, the effects of pince-nez were long lasting. While they rose to popularity as a way to avoid the stigma of glasses wearing, they played a role in making it socially acceptable to be visually challenged. Come back next time to learn how pince-nez and rimless glasses laid the foundation for eyewear becoming cool.