The form of a given lens is determined by "base curve selection." The base curve of a lens is the surface curve that serves as the basis or starting point from which the remaining curves will be calculated. For semi-finished lens blanks, the base curve will be the factory-finished curve, which is generally located on the front of the blank. The surfacing laboratory is ultimately responsible for choosing the appropriate base curve for a given prescription (or focal power) before surfacing the lens. For finished lens blanks, which have already been fabricated to the desired power, the manufacturer chooses the curves beforehand.

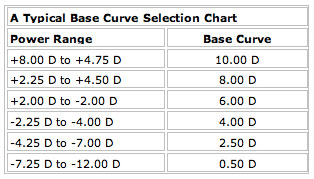

Manufacturers typically produce a series of semi-finished lens blanks, each with its own base curve. This "base curve series" is a system of lens blanks that increases incrementally in surface power (e.g., +0.50 D, +2.00 D, +4.00 D, and so on). Each base curve in the series is used for producing a small range of prescriptions, as specified by the manufacturer. Consequently, the more base curves available in the series, the broader the prescription range of the product. Manufacturers make base curve selection charts available that provide the recommended prescription ranges for each base curve in the series.

The base curve of a lens may affect certain aspects of vision, such as distortion and magnification, and wearers may notice perceptual differences between lenses with different base curves. Consequently, some practitioners may specify "match base curves" on a new prescription. Some feel that these perceptual differences should be minimized by employing the same base curves when the wearer obtains new eyewear. This would conceivably make it easier for particularly sensitive wearers to "adapt" to their new eyewear.

However, changes in the spectacle prescription will also create unavoidable perceptual differences. Moreover, the wearer will generally adjust to these perceptual differences within a week or so. If the same base curve is continually used as the wearer's prescription changes, which might necessitate a change in the manufacturer's recommended base curve, the peripheral optical performance of the lens may suffer as a consequence. When duplicating lenses of the same lens material, design, and power, matching base curves should not pose a problem—and is a recommended practice. Otherwise, unless the wearer has shown a previous sensitivity to base curve changes, you should use the manufacturer's recommended base curve when changing the prescription, or when using different lens materials and/or designs.

There are some exceptions to this rule, though they are rare. Some wearers with particularly long eyelashes may have been given steeper base curves at some point in order to prevent their lashes from rubbing against the back lens surface when their vertex distance—or the distance between the lens and the eye—is small, though this practice is very uncommon. Additionally, some wearers with a significant difference in prescription between the right and left eyes may suffer from aniseikonia, or unequal retinal image sizes, and require unusual base curve combinations in order to minimize the magnification disparity produced by the difference in lens powers. In these situations, a discussion with the prescriber may be in order before changing base curves.

Since an almost infinite range of lens forms can produce the power of a lens, why choose one base curve over another? There are two principal factors that influence the selection of base curves (and their resulting lens forms):

- Mechanical factors

- Optical factors