Color vision perception is an amazing and complex process involving the eye and the brain, and recently, researchers at the National Eye Institute (NEI) have decoded brain maps of human color perception. The brain uses light signals detected by the retina’s cone photoreceptors as the building blocks for color perception. Three types of cone photoreceptors detect light over a range of wavelengths. The brain mixes and categorizes these signals to perceive color in a process that is not well understood. However, a recent study opens a window into how color processing is organized in the brain, and how the brain recognizes and groups colors in the environment.

To examine this process, researchers used magnetoencephalography or “MEG,” a 50-year-old technology that noninvasively records the tiny magnetic fields that accompany brain activity. The technique provides a direct measurement of brain cell activity and reveals the millisecond-by-millisecond changes that happen in the brain to enable vision. The researchers recorded patterns of activity as volunteers viewed specially designed color images and reported the colors they saw.

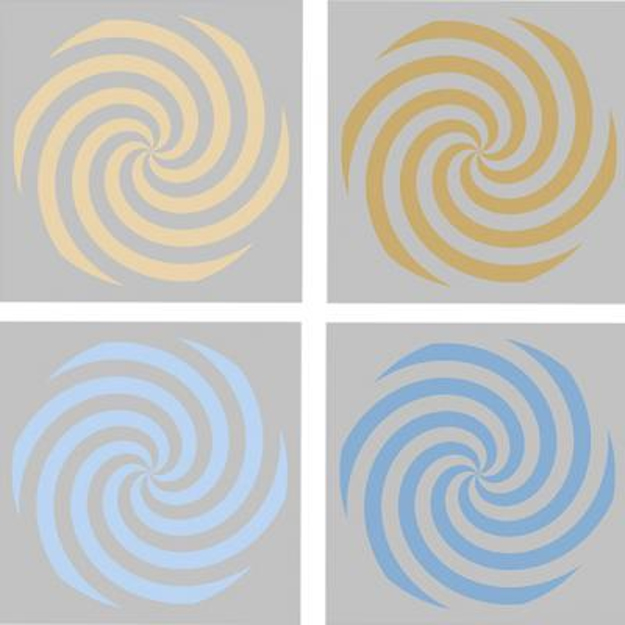

The researchers worked with pink, blue, green, and orange hues so that they could activate the different classes of photoreceptors in similar ways. These colors were presented at two luminance levels – light and dark. They used a spiral stimulus shape, which produces a strong brain response. The researchers found that study participants had unique patterns of brain activity for each color. With enough data, the researchers could predict from MEG recordings what color a volunteer was looking at – essentially decoding the brain map of color processing, or “mind-reading.”

|

| Colored stimuli in yellow (top) and blue (bottom). Light luminance level versions are on the left, dark versions on the right. Volunteers used a variety of names for the upper stimuli, such as “yellow” for the left and “brown” for the right, but consistently used “blue” for both the lower stimuli. Courtesy: National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health (NEI/NIH) |

In a variety of languages and cultures, humans have more distinct names for warm colors (yellows, reds, oranges, browns) than for cool colors (blues, greens). It’s long been known that people consistently use a wider variety of names for the warm hues at different luminance levels (e.g. “yellow” versus “brown”) than for cool hues (e.g. “blue” is used for both light and dark). The new discovery shows that brain activity patterns vary more between light and dark warm hues than for light and dark cool hues. The findings suggest that our universal propensity to have more names for warm hues may actually be rooted in how the human brain processes color, not in language or culture.

Bevil Conway, Ph.D., chief of NEI’s Unit on Sensation, Cognition and Action, who led the study, notes, “color is a powerful model system that reveals clues to how the mind and brain work. … Using this new approach, we can use the brain to decode how color perception works – and in the process, hopefully uncover how the brain turns sense data into perceptions, thoughts, and ultimately actions.”

For more information about how the eye processes and perceives color, go to our CE, Achromatopsia, at 2020mag.com/ce.