Estimates are that 12.7 million people worldwide are blind due to corneal disease, yet only one in 70 who need corneal transplants from a human donor receives them, most likely because donated human corneas are scarce in countries where the need for them is greatest. A recent study had promising results, however, using a bioengineered implant as an alternative to the transplantation of donated human corneas. (Linköping University. "Bioengineered cornea can restore sight to the blind and visually impaired: Bioengineered corneal tissue for minimally invasive vision restoration in advanced keratoconus in two clinical cohorts." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 11 August 2022. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/08/220811135339.htm>.)

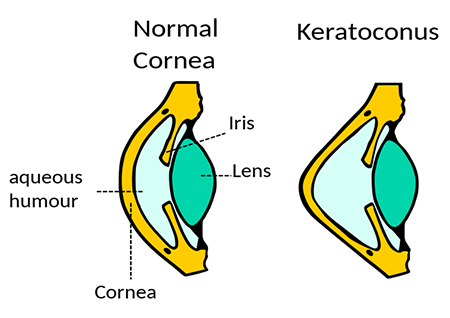

The researchers have developed a new, minimally invasive method for treating keratoconus and other corneal diseases. Keratoconus occurs when the cornea thins and gradually bulges outward into a cone shape, causing blurred vision and sensitivity to light and glare. In the early stages, keratoconus vision problems may be corrected with glasses or soft contact lenses. Later, rigid, gas permeable contact lenses or scleral lenses may be used. In advanced stages, a corneal transplant may be needed. Corneal collagen cross-linking, a procedure that combines prescription eye drops and UVA light to stiffen the cornea, also may help to slow or stop keratoconus from progressing. However, access to these treatments, transplants in particular, may be limited in low and middle-income countries.

| |

Twenty people who were either blind or on the verge of losing sight due to advanced keratoconus participated in the pilot clinical study and received the biomaterial implant. The surgeries had no complications, healing was quick, and an eight-week treatment with immunosuppressive eye drops was enough to prevent rejection of the implant. With conventional corneal transplants, the drops must be taken for a much longer time. The patients were followed for two years, and no complications were noted during that time.

What the researchers didn’t see coming were results beyond their expectations. The cornea's thickness and curvature were restored to normal, and participants' sight improved as much as it would have after a corneal transplant with donated tissue. Before the operation, 14 of the 20 participants were blind. After two years, none of them was blind, and three of the participants who had been blind prior to the study had perfect (20/20) vision after the operation.

Other benefits to this method are that the pig skin used is a byproduct of the food industry, making it easy to access and economical. What’s more, while donated human corneas must be used within two weeks, the bioengineered corneas can be stored for up to two years. And because the procedure is less invasive, it could be used in more hospitals to help more people. While additional study is needed on larger groups for regulatory approval and availability, researchers believe that the technology can be expanded to treat more eye diseases.

Learn about the unique structure and function of the cornea with our CE, Explore the Cornea, at 2020mag.com/ce.