US Pharm.

2006;31(9):20-34.

Urinary

incontinence (UI) can have a negative impact on an individual's quality

of life by lowering self-esteem and affecting psychological and physical

well-being. According to a study supported in part by the Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality, elderly Americans who are incontinent often

experience shame, disgust, embarrassment, and a less active social life, all

of which can lead to depression.1 Furthermore, elderly individuals

with UI are more likely than those without it to have symptoms of depression.

1

According to a recent survey,

called What Older Women Want, women ages 55 to 95 rated UI as number 5

among the top 10 unmet health priorities.2 This finding is

consistent with previous data showing that elderly women express more concerns

about living with disabilities than developing common illnesses.2

Despite these findings, UI is underdiagnosed and often underreported by

patients due to embarrassment or acceptance of the condition as a consequence

of aging, although it is not actually caused by aging.3,4

This article encourages

pharmacists to raise awareness of UI, educate patients about the condition,

and provide appropriate recommendations for treatment. By approaching UI as a

condition with underlying, though sometimes irreversible causes, pharmacists

can help manage patients well enough to improve symptoms and minimize

complications.5

Prevalence

UI affects

approximately 17 million Americans, including more than 50% of seniors in

hospitals or nursing facilities and 8% to 34% of community-dwelling seniors.

6,7 It is especially prevalent in women, with a greater than 45%

occurrence in those ages 50 to 59.8 Overall, data show that 17% to

55% of elderly women versus 11% to 34% of elderly men are affected.9

UI leads to decreased quality of life in up to 44% of affected women.2

Furthermore, the presence of UI is a predictive factor for nursing home

admission.9,10 One study found that the prevalence of depression

was 15.5% in women with UI, compared with only 9.2% in women without UI.11

Management of UI presents a significant financial strain on patients, health

care facilities, and industry and government agencies providing health care

funding, incurring a direct annual cost of $26.5 billion.12

Continence and UI Complications

Normal urination is

a complex process, requiring both a bladder that can store and expel urine and

a urethra that can close and open appropriately. Normal micturition occurs

when bladder contraction is coordinated with urethral sphincter relaxation.

Additional factors necessary for continence are related to a patient's

cognitive function, dexterity, social awareness, motivation, and locomotive

ability. The central nervous system integrates control of the urinary tract.

The inability to control urination in a socially appropriate manner is known

as UI.

Complications associated with

UI include skin rashes, pressure ulcers, and indirectly, falls and fractures.

Use of an indwelling catheter is associated with patient discomfort, use of

drugs for bladder spasms, and an increased risk of life-threatening

infections, bladder stones, and cancer.13 Decreases in sleep,

social interaction, and self-esteem can affect psychological well-being. In

addition, family members and health care facility staff who care for a

functionally dependent patients with UI may experience increased levels of

stress.

Diagnostic Assessment

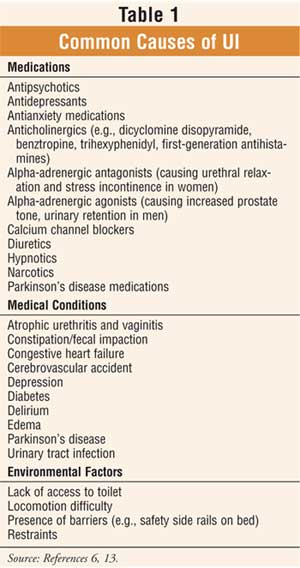

Distinguishing

which type of UI a patient has is critical for prescribing the appropriate

treatment; this begins with determining the cause of UI (TABLE 1). This

process comprises a thorough physical examination as well as an evaluation of

the patient's medical history. This would include an evaluation of the

patient's medication history to rule out reversible medication-related causes

of UI. Pharmacists should have an active role in the assessment process, since

UI due to anticholinergic, narcotic, and beta-adrenergic drugs can be improved

by switching or discontinuing medication or modifying the dosage schedule when

appropriate.3 The pharmacist's expertise can prove to be a valuable

addition to the team approach of increasing quality of life and decreasing

cost of care.14

The physical exam should

assess the patient's medical condition as well as cognition, dexterity, and

mobility. An examination of the abdomen, genitals, pelvis, and rectum should

also be conducted. Edema and neurologic abnormalities may contribute to UI

and, therefore, should be ruled out. Since it may be difficult to correctly

diagnose UI, patients should also be examined for urinary tract infection,

post-void residual volume, and simple cystometry measures of bladder capacity

and stability.3 Detecting potentially reversible causes of UI

should always be a priority. Urodynamic instruments such as a uroflowmeter and

cystometer should not be used as screening tools, because results of these

tests do not differ significantly for continent and incontinent patients;

however, using these tools as confirmatory tests may help to determine a

therapeutic approach.3

Classifications

There are a number

of different types of UI, and more than one type may be present simultaneously

or overlap with one another.

Stress Incontinence

Stress incontinence

is common among senior women, especially in ambulatory clinic settings.

15,16 It is usually associated with weakened supporting tissue, which

results in hypermotility of the urethra and bladder outlet.15

Coughing, sneezing, laughing, exercising, or any other physical activity that

increases intra-abdominal pressure may cause uncontrolled urination.15,17

Symptoms can be infrequent, with small amounts of urine and no need for

specific treatment, to severe and bothersome, necessitating surgical

correction.16 Vaginal childbirth, estrogen de ficiency, obesity,

and/or surgery can contribute to stress incontinence. While stress

incontinence is rare in men, it can occur in such patients after transurethral

surgery and/or radiation therapy for lower urinary tract malignancy (e.g.,

prostate cancer) when the anatomic sphincters are damaged.16

Urge Incontinence

The most common

type of UI among those age 85 or older is urge incontinence, which is caused

by abnormal involuntary detrusor muscle contractions (i.e., detrusor

overactivity).18,19 It is characterized by an abrupt, strong desire

to urinate as well as frequent urination (e.g., more than every two hours) and

nocturia.16 Patients may lose urine on their way to the toilet, and

some may experience a degree of urinary retention. Causes of urge incontinence

include central nervous system disorders (e.g., stroke, dementia,

parkinsonism, spinal cord injury) and lower genitourinary conditions (e.g.,

tumors, stones, diverticula, outflow obstruction).16 It is possible

that symptoms of urge incontinence among the el derly may be misinterpreted

as agitation related to a behavioral disturbance secondary to dementia.

Overflow Incontinence

Overflow incontinence occurs from distention of the bladder as a result of an inability to empty normally. It is the most common form of incontinence among elderly men. Symptoms include frequent urination, urgency, dribbling, urge incontinence, and stress incontinence. Causes of overflow incontinence vary and include uterine prolapse, urethral strictures, prostate enlargement, diabetes, and spinal cord injury.18

Mixed Incontinence

Mixed incontinence

occurs in 50% to 60% of patients with UI and is characterized by symptoms of

both urge incontinence and stress incontinence.20 It is most

commonly seen among older women. Mixed incontinence is also commonly seen as a

combination of urge and functional incontinence among nursing home residents.

15

Functional Incontinence

Functional

incontinence may be caused by cognitive impairment, psychological impairment,

impaired mobility, medications, or dexterity problems that render the patient

unable or unwilling to toilet properly.6,17 For example, delirium

promotes incontinence by increasing disorientation and decreasing patient

awareness of the need to void. Mobility impairment affects the ability to

reach the toilet in time.3 Functional UI may exacerbate other types

of persistent incontinence.15

Complex History of UI

Incontinence

associated with pain, hematuria, recurrent infection, pelvic complications

(e.g., bladder cancer, bladder stones, prostate cancer), herniated disks, and

metastatic tumors is classified as complex history of UI. This type of UI

usually requires a specialized management approach.13,21

Management of UI

Treatment options

for the management of UI include both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic

therapy.3

Nonpharmacologic

Intervention

Nonpharmacologic

therapy is recommended in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. Nonpharmacologic

interventions that are helpful in the management of UI include--but are not

limited to--behavior modifications such as bladder control training and dietary

modification, prompted voiding, and use of absorbent products and catheters.

Behavior modification, used

alone or in combination with other treatment modalities, is safe, effective,

and the least invasive treatment for UI.17,22,23 Bladder control

training can be useful for managing UI. Kegel exercises, which involve

alternating contraction and relaxation of the pubococcygeus muscle, improve

pelvic floor muscle tone and help the bladder store urine for longer periods

of time. Patients should begin by performing 10 alternating three-second

contractions and relaxations per day and gradually increase to 80 to 150

10-second contractions and relaxations per day.2 In some cases,

biofeedback and electrical stimulation may be recommended in conjunction with

pelvic floor exercises to help control urge and overflow incontinence.24

Another method of bladder control training, known as bladder retraining

, involves gradually increasing the time between voiding by 15-minute

increments each week until voiding occurs every three to four hours.2

Dietary modifications can also

be useful for managing UI. Patients should avoid certain foods known to

irritate the bladder. These include carbonated or caffeinated drinks, spicy

foods, citrus fruits and juices, artificial sweeteners, and diuretics.

However, avoiding fluid is not advised, as this may worsen symptoms by

irritating the bladder.

Functional incontinence should

be managed by using environmental manipulations, scheduled toileting, prompted

voiding (e.g., asking the patient "Do you want to use the toilet?"), toilet

substitutes (e.g., portable commode), absorbent pads and undergarments, and

attention to skin care (e.g., cleansing and drying thoroughly).3

Absorbent products may not only provide overnight protection but also allow

residents to resume social activities.17

In the nursing facility

environment, easing restriction on movement while monitoring patient safety

may be all the intervention necessary to improve symptoms of UI in some

patients.22 For other patients, the use of pessaries, intermittent

catheters, or chronic indwelling catheters may be necessary. On June 28, 2005,

the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued interpretive guidelines

for the use of indwelling catheters in the treatment of UI. The guidelines

redefined UI as any wetness on the skin.25 The new guidance for

nursing homes is labeled Tag F315 and contains interpretive guidelines, a new

investigative protocol, and compliance and severity guidance.25

Only after other treatments

have been tried should surgical intervention (e.g., sling procedure or bladder

neck suspension) be recommended to alleviate UI.3

Pharmacologic Intervention

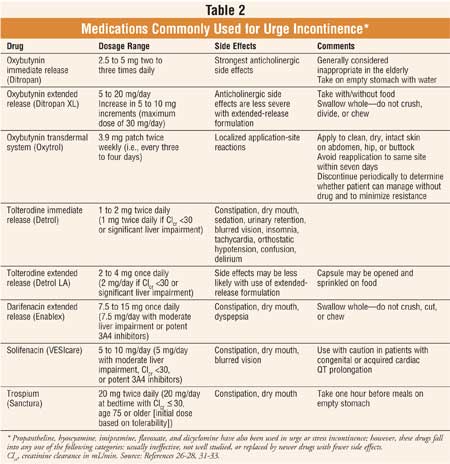

Anticholinergic Agents:

Anticholinergic agents (Table 2) are first-line pharmacotherapy for

urge incontinence, with recommended titration to tolerability and efficacy.

They are associated with adverse reactions (e.g., sedation, constipation, dry

mouth, blurred vision, tachycardia, confusion, delirium, an increased risk of

heat prostration) and should be used with caution in the elderly when benefit

outweighs risk.26 These agents should also be used with caution in

patients with urinary obstruction, angle-closure glaucoma (treated),

hyperthyroidism, reflux esophagitis, hiatal hernia, heart disease,

hypertension, renal or hepatic disease, prostatic hyperplasia, autonomic

neuropathy, ulcerative colitis, or intestinal atony.

Alpha-Adrenergic

Agonists:

Alpha-adrenergic agonists (e.g., pseudoephedrine) are used for stress

incontinence, often in combination with estrogen.15 Although well

tolerated, they may precipitate anxiety, agitation, hypertension, and cardiac

arrhythmias and should be used with caution in patients with hyperthyroidism,

angina, hypertension, or cardiac arrhythmias.18,22

Duloxetine: Duloxetine increases

urinary sphincter striated muscle tone. While experience with this agent is

limited, it appears to be effective for outlet incompetence in stress

incontinence.27

Alpha-Adrenergic

Antagonists:

Alpha-adrenergic antagonists (e.g., prazosin 0.5 to 2 mg twice daily,

doxazosin 1 to 8 mg once daily, terazosin 1 to 10 mg once daily, tamsulosin

0.4 to 0.8 mg once daily) are used in conjunction with nonpharmacologic

treatments, catheterization, and surgery for patients with overflow

incontinence.6 Bedtime administration is recommended to minimize

the risk of orthostatic hypotension associated with these agents.

Estrogen:

Studies have shown that oral estrogen in hormone replacement dosages has no

effect on stress incontinence episodes in hypoestrogenemic incontinent women.

15 In combination with an alpha-agonist, however, estrogen appears to be

effective for stress incontinence.15 Topical estrogen, applied

chronically or intermittently (i.e., one- to two-month course), is used to

treat urge incontinence or irritative voiding symptoms in women with atrophic

vaginitis and urethritis.15 Therapy usually consists of 0.5 to 1 g

of vaginal cream applied nightly for one to two months and then two to three

times per week, thereafter. Several months of therapy is usually required to

elicit therapeutic benefit.15 Estrogen delivered via a vaginal ring

(inserted every three months), vaginal tablet (inserted two times per week),

or transdermal system (e.g., a patch applied two times per week) are also

available; however, use of these treatments is generally not preferred in

patients with only local symptoms.28 These agents should be used

for the shortest duration possible.28 In patients with an intact

uterus who are using estrogen, progestin is recommended for 10 to 14 days

every four weeks.

Tailored Therapy:

Therapeutic interventions for mixed incontinence are focused on the most

troublesome symptoms. Treatment for functional incontinence concentrates on

improving functional status by discontinuing medications causing UI, treating

comorbid medical conditions, and reducing environmental restrictions. If these

measures fail, anticholinergics may be effective. Even in patients with severe

dementia, bladder training and medications have been shown to improve

incontinence.13

Botulinum-A Toxin:

Studies are reporting the use of botulinum-A toxin injected into the detrusor

muscle as a possible treatment option for patients with severe overactive

bladder (e.g., traumatic spinal cord injury) resistant to maximal doses of

anticholinergic agents and all conventional treatments.29,30

Conclusion

While UI is common

in women, it can be treated and controlled. Inadequate recognition and

management of UI can have a significant impact on a patient's quality of life

and cost of care. Appropriate treatment can assist with the avoidance of

complications and consequences including depression, pressure ulcers, falls,

and fractures. Additionally, pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions

can help avoid functional dependence associated with UI. The pharmacist's

expertise proves a valuable addition to the team approach of decreasing cost

of care while increasing quality of life for patients with UI. Pharmacists can

help rule out medication-related causes of UI, recommend appropriate

medication therapy, and help patients avoid adverse drug reactions.

REFERENCES

1. Dugan E, Cohen

SJ, Bland DR, et al. The association of depressive symptoms and urinary

incontinence among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:413-416.

2. Radcliffe-Branch D, Tannenbaum C. A review of older women's health

priorities. Geriatrics Aging. 2006;9:124-128.

3. Rawlins S, Tillmanns AK. Menopause and current management. In: Youngkin EQ,

Sawin KJ, Kissinger JF, et al. Pharmacotherapeutics: A Primary Care

Clinical Guide. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall;

2005:281.

4. Johnson TM 2nd, Busby-Whitehead J. Diagnostic assessment of geriatric

urinary incontinence. Am J Med Sci. 1997;314:250-256.

5. Levenson S. A tool for managing urinary incontinence. Caring for the Ages

. 2006;July:18-19.

6. Beers MH, Berkow R. The Merck Manual of Geriatrics. 3rd ed.

Whitehouse Station, NJ; Merck & Co. 2000: 965-980.

7. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Advisory Board. Barriers to

Rehabilitation of Persons with End-stage Renal Disease. Workshop Summary

Report. March 7-9, 1994; Bethesda, MD.

8. Ouslander JG, Shih YT, Malone-Lee J, Luber K. Overactive bladder: special

considerations in the geriatric population. Am J Manag Care.

2000;6:S599-S606.

9. Thom DH, Haan MN, Van Den Eeden SK. Medically recognized urinary

incontinence and risks of hospitalization, nursing home admission and

mortality. Age Ageing.1997;26:367-374.

10. Nuotio M, Tammela TL, Luukkaala T, Jylha M. Predictors of

institutionalization in an older population during a 13-year period: the

effect of urge incontinence. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.

2003;58:756-762.

11. Vigod SM, Stewart DE. Major depression in female urinary incontinence.

Psychosomatics. 2006;47:147-151.

12. Lawrence M, Guay DR, Benson SR, Anderson MJ. Immediate-release oxybutynin

versus tolterodine in detrusor overactivity: a population analysis.

Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:470-475.

13. Klusch L. Understanding RAPS. Des Moines, IA: Briggs Corporation;

1998:23-29.

14. Wade WE. Managing dosage alteration needs in the elderly. Clinical Consult

Newsletter-American Society of Consultant Pharmacists Vol. 11, No. 10 October

1992.

15. Ouslander JG, Johnson II TM. Incontinence. In: Hazzard WR, Blass JP,

Halter JB, et al. Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 5th

ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 2003:1571-1586.

16. Kane RL, Ouslander JG, Abrass IB. Essentials of Clinical Geriatrics

. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 1999:181-230.

17. Couture JA, Valiquette L. Urinary incontinence. Ann Pharmacother.

2000;34:646-655.

18. Nasr SZ, Ouslander JG. Urinary incontinence in the elderly. Causes and

treatment options. Drugs Aging.1998;12:349-360.

19. Weinberger MW. Conservative treatment of urinary incontinence. Clin

Obstet Gynecol. 1995;38:175-188.

20. Rackley R, Kursh ED. Evaluation and medical management of female urinary

incontinence. Compr Ther. 1996;22:547-553.

21. Scientific Committee of the First International Consultation on

Incontinence. Assessment and treatment of urinary incontinence. Lancet.

2000;355:2153-2158.

22. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Urinary incontinence in

adults: acute and chronic management. Clinical practice guidelines number 2

(1996 update). March 1996. AHCPR Pub. No. 96-0682.

23. Burgio KL, Locher

MA, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs. drug treatment for urge urinary

incontinence in older women. JAMA. 1998;280:1995-2000.

24. National Institute on Aging. Urinary Incontinence. Available at:

www.niapublications.org/ agepages/urinary.asp. Accessed August 2, 2006.

25. Department of Health & Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services. CMS Manual System. Pub. 100-07 State Operations Provider

Certification. Transmittal 8. June 28, 2005. Available

at:www.cms.hhs.gov/transmittals/downloads/R8SOM.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2006.

26. Semla TP, Beizer JL, Higbee MD. Geriatric Dosage Handbook. 10th ed.

Cleveland: Lexi-Comp, Inc.; 2005.

27. Beers MH, Porter RS, Jones TV. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy

. 18th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories; 2006:1951-1960.

28. My Epocrates Version 8.00. Available at: www.epocrates.com. Accessed

August 23, 2006.

29. Schmid DM, Sauermann P, Werner M, et al. Experience with 100 cases treated

with botulinum-A toxin injections in the detrusor muscle for idiopathic

overactive bladder syndrome refractory to anticholinergics. J Urol.

2006;176:177-185.

30. Patki PS, Hamid R, Arumugam K, et al. Botulinum toxin-type A in the

treatment of drug-resistant neurogenic detrusor overactivity secondary to

traumatic spinal cord injury. BJU Int. 2006;98:77-82.

31. Cafiero AC, Rosenberger M, Hajjar ER. Treating urge incontinence: the role

of the new pharmacologic agents. Assisted Living Consult. 2006;2:20-23,

30.

32. Urinary Incontinence. Table 6: Potential Medication Interventions by Type

of Incontinence. American Medical Directors Association Web site. Available

at: www.cpgnews.org/UI/images/table6.jpg. Accessed August 2, 2006.

33. DeMaagd G, Geibig J. An Overview of Overactive Bladder and Its

Pharmacological Management with a Focus on Anticholinergic Drugs. P&T.

2006:462-474.

To comment on this article, contact

[email protected].