UNDERSTANDING DRY EYE, 2017 UPDATE

By Linda Conlin, ABOC, NCLEC

Release Date: July 1, 2017

Expiration Date: May 3, 2019

Learning Objectives:

- Gain knowledge of ocular anatomy and physiology through an understanding of dry eye syndrome and its causes and symptoms.

- Understand how to manage dry eye syndrome using a range of options from over-thecounter treatments to surgical intervention.

- Learn about contact lens fitting considerations for patients with dry eye syndrome to increase comfort and wearing time.

Description:

The view of the world through a child's eye is much different than that of an adult, both literally and figuratively. With that in mind, imagine how a child perceives an exam room or a dispensary, especially if it is their first experience visiting an optical practice. This course will create awareness around the importance of providing a welcoming environment for children's eye exams, the selection of kid's frames, lens materials and lens enhancements, as well as provide tips on how to dispense glasses to children.

Credit Statement:

This course is approved for one (1) hour of CE credit by the National Contact Lens Examiners (NCLE). 1 hour, Technical, Level I Course CTWJHI001-1.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

With over 30 years of experience and licensed in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, Linda Conlin is a writer and lecturer for regional and national meetings. She is chair of the Connecticut Board of Examiners for Opticians and is a manager for OptiCare Eye Health and Vision Centers, a multidisciplinary ophthalmic practice in Connecticut.

You may be able to “Cry Me a River” but still have dry eye syndrome. Multiple factors in addition to quantity of tears contribute to the syndrome. Knowing the causes, symptoms and treatments for dry eye provides the tools for increased patient comfort and contact lens wear success.

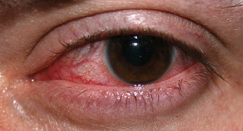

FIGURE 1 |

| Keratitis |

Dry eye syndrome is the lack of sufficient lubrication and moisture on the surface of the eye because of decreased quality or quantity of tears. As a result, patients suffer constant discomfort from eye irritation and longer healing time if they have had refractive surgery. Symptoms include persistent dryness, scratchiness, burning, foreign body sensation, blurred vision, light sensitivity and surprisingly, tear overproduction (Fig. 1).

Fifty percent of contact lens dropouts are associated with discomfort from dry eye. The syndrome is more common in smokers and women, especially following blepharoplasty that resulted in incomplete lid closure. Dry eye affects an estimated 10 to 30 percent of the population, although the actual percentage may be much higher because not everyone who may have the syndrome seeks professional attention. What’s more, the incidence of dry eye is increasing due to an aging population as well as increased computer use. When using computers, people blink at a rate that is about one-third the normal blink rate, decreasing lubrication of the eye.

CLIDE

With the prevalence of the syndrome an acronym developed, but unlike most acronyms, this one–CLIDE—describes two issues. The first is for the condition known as Contact LensInduced Dry Eye, and the second is for the causes of dry eye: Climate, Drugs, Environment. The acronym becomes a handy tool when we understand the causes of dry eye.

The incidence of dry eye increases in dry, dusty, windy and cold climates. Of the top 20 U.S. cities for dry eye, Las Vegas ranks first, and five Texas cities are included in the group as one might expect, but so are Boston and Newark, N.J. In these cities, the effects of drying can take dramatic turns, especially for individuals working outside. In Arizona, another “dry eye state,” the Arizona Fall League is a training ground for promising baseball players, in addition to various spring training sites. To combat dry eye, some players take dietary supplements. The supplements contain anti-inflammatory compounds which help stimulate tear production.

Drugs such as antihistamines, antidepressants, antihypertensives which are frequently diuretics, Parkinson’s medications and oral contraceptives can include dry eye as a side effect. Aside from climate, environments with dry heat or air conditioning can contribute to dry eye. Other factors that contribute to dry eye include insufficient blinking as can occur with computer use, long-term contact lens wear, eyelid disease, tear gland deficiency, aging, menopause and diseases such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, ocular rosacea and Sjögren’s syndrome. (See Fig. 2)

FIGURE 2 |

| Causes of dry eye |

Sjögren’s syndrome is a disorder of the immune system characterized by dry eyes, dry mouth and fatigue. It is commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, and results in a decreased production of tears, saliva and sweat. It occurs more often in women over age 40 and is treated with increased water intake, eye drops and drugs.

Sjögren’s syndrome gained national attention in the late summer of 2011 when tennis pro Venus Williams, then 31, announced she suffered from the syndrome and its symptoms. Williams cited fatigue as the reason she withdrew from her 13th U.S. Open. Williams has since come back to competition and currently ranks 11th in the WTA.

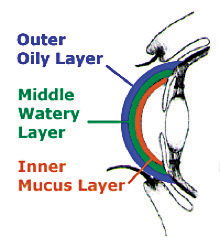

FIGURE 3 |

| Layers of tear film |

TEARS

The quality and quantity of tears are the critical factors in dry eye syndrome, so let’s look at the source and composition of tears. The tear film consists of three layers: lipid, aqueous and mucin (Fig. 3). The outer lipid layer is oily and prevents the evaporation of tears. It is manufactured by the meibomean glands located on the lid margins. The middle aqueous layer is the largest portion of the tear film, contains dissolved sticky proteins or mucins and supplies oxygen to the cornea. The lacrimal glands above the outer canthus secrete this layer of the tear film. The inner mucin layer produced by the goblet cells in the conjunctiva keeps the highest concentration of mucins at the surface of the eye. Mucins help stabilize and spread tear film, which prolongs break up time. It’s easy to see how poor composition or inadequate production of any layer of the tears could lead to insufficient lubrication and moisture on the surface of the eye.

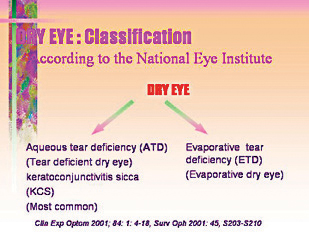

DRY EYE CLASSIFICATION

The National Eye Institute has identified two classifications of dry eye syndrome based on the type of tear deficiency: aqueous tear deficiency (ATD) and evaporative tear deficiency (ETD) (Fig. 4). Aqueous tear deficiency, also called keratitis sicca, is an insufficiency in the aqueous or watery layer of tears and is the most common type of dry eye. Causes include lacrimal deficiency, lacrimal gland duct obstruction, reflex block and systemic drugs. Evaporative tear deficiency is an insufficiency of the lipid or oily tear layer which functions to slow tear evaporation. Causes include meibomian oil deficiency, disorders of the lids, low blink rate, drug side effects, vitamin A deficiency, contact lens wear and ocular surface disease such as occurs from allergies. In addition, patients can suffer from a combination of both ATD and ETD.

FIGURE 4 |

| Dry eye classification |

TESTING

Eyecare practitioners (ECPs) commonly use two tests to classify dry eye syndrome: the Schirmer test and the Break Up Time test. The Schirmer test evaluates the quantity of tears. The practitioner places the folded end of a thin strip of filter paper inside the lower lids of both eyes. One can perform the test without an anesthetic. However, the test is more accurate with an anesthetic because irritation from the paper may temporarily increase tear production. After five minutes, the practitioner evaluates the moisture of the eye by observing how much of the filter paper became wet through capillary action. Fifteen millimeters or more is considered normal, nine to 14 millimeters indicates mild insufficiency, four to eight millimeters indicates moderate insufficiency, and less than four millimeters indicates a severe condition. In conjunction with the Schirmer test, applying fluorescein drops will indicate whether tears can drain through the lacrimal duct into the nose. A similar procedure is the cotton thread test. The practitioner uses a chemically treated cotton thread instead of filter paper. The thread changes color as it moistens. The practitioner then measures the length of the color change on the thread. Lengths of less than 10 millimeters indicate dryness. The advantages of the cotton thread test are that it indicates results in 15 seconds as opposed to five minutes, and it does not require anesthetic drops.

The B.U.T. (Break Up Time) test evaluates tear quality by measuring how long it takes for dry spots to appear on the cornea after a blink. The ECP applies fluorescein to the patient’s eye and then observes the tear film after a blink while the patient tries to avoid the next blink. The practitioner counts by seconds until a dry spot appears. A break up time of more than 10 seconds is normal, from five to 10 seconds is marginal, and less than five seconds is low.

A 2012 study by Isabelle Jabert, OD, and colleagues at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, found that increased lower lid margin sensitivity was related to more concentrated tears and meibomian gland dysfunction, both of which contribute to dry eye symptoms. ECPs can conduct the sensitivity test, called esthesiometry, in the office using an esthesiometer or a cotton tipped applicator applied to the lower lid margin. The patient’s reaction to the least amount of pressure indicates sensitivity that is normal, reduced or absent. Interestingly, the study’s finding of a higher concentration of tears indicates an aqueous deficiency, while the additional finding of meibomian gland dysfunction indicates an evaporative deficiency. Patients with reduced lower lid margin sensitivity, therefore, are likely to have a combination of the two classifications of dry eye syndrome. The relationship between lid margin sensitivity and dry eye has been born out in subsequent studies.

Other diagnostic tests for dry eye include: tear film osmolarity (tests the saltiness of tears) and tear meniscus height. The tear meniscus is the thin strip of tear fluid at the upper and lower lid margins. A low or absent meniscus is an indication of dry eye.

TREATMENTS

While no cure for dry eye syndrome presently exists, ECPs can help patients manage the symptoms. For mild cases, this can be as simple as encouraging the patient to drink more water. Adult women should have 91 ounces or about 12 glasses of water a day, while men should have 125 ounces or 16 glasses. Studies have shown that increasing omega-3 and vitamin A intake is beneficial. Both of those nutrients are found in some fish oils and maintain mucous membranes. Severe or prolonged vitamin A deficiency is characterized by dry eye and changes to the cornea that can result in corneal ulcers, scarring and blindness. (This is why Mom told you to eat your carrots!) Patients should also avoid caffeine because it is a diuretic.

Other things patients can do to alleviate dry eye symptoms include wraparound sunglasses with side shields, indoor air filters and humidifiers, checking with their doctors to change medications that have dry eye as a side effect, and resting their eyes during visually demanding tasks. Remind patients of the 20/20/20 rule. After 20 minutes of a visually demanding task such as reading or computer work, rest the eyes for 20 seconds by gazing at a point 20 feet away.

Blinking is an important part of keeping the eye moist and lubricated. Blinking facilitates tear drainage, eliminates debris, spreads lipids across the tear film and nourishes the cornea. Research indicates that patients with dry eye have a higher blink rate, and a higher blink rate is associated with a shorter tear break up time. The chicken-or-the-egg question remains, however. Does a higher blink rate result in a shorter break up time or is it due to the irritation from the dry eye itself? When medications are used to treat dry eye, the blink rate usually slows.

Artificial tears or contact lens rewetting drops may be all that is needed to alleviate the symptoms of mild dry eye. However, drops containing preservatives may cause irritation and patients shouldn’t use them more than four times a day. Patients can use non-preserved drops in single use vials more often. When contact lens wearers use artificial tears, they should remove their lenses and wait 15 minutes before re-inserting them. Patients can also use ointments applied before sleeping. Instruct patients that drops to “get the red out” are vasoconstrictors and may not lubricate the eye. What’s more, a tolerance to the drops can build up and result in more redness.

For some dry eye patients, such home and OTC remedies will mask the problem for a short time, and other measures need to be taken. For instance, blepharitis, an inflammation of the lid follicles, blocks production of the oily component of tears. One way to reduce the inflammation is to gently rub the lids with a warm washcloth, then massage the lids near the base of the lashes with baby shampoo or lid scrubs. Taking a different aim at inflammation, Allergan introduced Restasis cyclosporine emulsion in 2003 to treat dry eye symptoms. It is an immunosuppressant that reduces inflammation, and in this way, it helps increase natural tear production. Patients need to administer the drops only twice a day, and it can be used in conjunction with artificial tears.

A 1998 study at the University of Iowa found that androgen levels in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction were abnormally low. Then in 2002, Charles Connor, OD, and Charles Haine, OD, of the Southern College of Optometry presented research showing that transdermal testosterone cream applied to the upper eyelids improved tear production and meibomian gland secretion in subjects after three weeks. Post-menopausal women showed the greatest improvement while men showed the least improvement. Since then, testosterone drops have come into use. These off-label uses of testosterone cream and drops are not yet FDA approved.

Punctal plugs are another common inoffice treatment for dry eye. Biocompatible plugs are inserted into the upper, lower or both puncta of the tear ducts to block drainage, and thereby increase tear film and surface moisture on the eye. There are two types of plugs. Semi-permanent plugs are durable and made from soft plastic materials such as silicone. Dissolvable plugs, made from materials that the body can absorb such as collagen, last anywhere from a few days to several months. Frequently they are used to prevent dry eye after refractive surgery. Both types of plugs can be removed by flushing with saline. Other punctal occlusion methods are more invasive. Those include punctal patching in which a tiny patch from the sclera is sutured over the punctum, cauterization of the punctum and ligation, adhesion, or excision of the tear duct.

CONTACT LENS OPTIONS

As you recall, CLIDE also is an acronym for Contact Lens-Induced Dry Eye. In this condition, the presence of the contact lens, as well as decreased corneal sensitivity from long-term contact lens wear, disrupts normal tear film, resulting in a shorter break up time. While the practitioner must have special consideration for these patients, there are a variety of contact lens options within the categories of rigid and soft lenses.

Rigid lenses are less susceptible to dehydration on the eye, but dry eye patients may have a longer adjustment time due to edge awareness. These lenses may not work well in dry environments if the tear film is compromised. Consider corneal refractive therapy for dry eye patients, especially those who have worn rigid lenses. With CRT, the patient wears rigid lenses overnight to reshape the cornea and eliminate the need for corrective lenses. Wearing the lenses only overnight reduces tear evaporation and the risk of drying during the day. For severe dry eye cases, rigid scleral lenses can become a prosthetic ocular surface. The lens is designed with computer-assisted lathe cut back curves to vault the cornea. Saline in the dome continually bathes the cornea to provide relief.

High water content soft lenses can be problematic for dry eye patients. The lenses themselves may draw moisture from tears to maintain hydration. Silicone hydrogel lenses are a better choice because they have high oxygen transmission but low water content. Some silicone hydrogel lenses have on-eye wettability. It is a surface treatment that accommodates tear film behind the lens and reduces the friction between the lids and the lens for better comfort. Oneday disposable lenses are another good option. Some of the new lenses have a water and oxygen content similar to that of the cornea, and a surface treatment designed to mimic the lipid layer of the tear film. What’s more, contact lenses with molecular imprinting are becoming available. CooperVision Proclear lenses contain molecules that attract and surround themselves with water, and are the only lenses with FDA approval to label them as possibly improving comfort for wearers who experience dryness. In addition, researchers are developing daily disposable and silicone hydrogel lenses imprinted with an adjustable release comfort agent.

Contact lens solutions also are an important consideration for dry eye patients. Some solutions work better with certain contact lens materials than others. Check with the lens manufacturer for solution recommendations. Advise patients against using generic solutions which can vary from purchase to purchase. Because proteins build up more quickly on lenses for dry eye patients, recommend rub and rinse types of solutions to provide better cleaning. Intolerance to preservatives in solutions can result in dry eye. Peroxide disinfection systems eliminate preservative intolerance problems as well as the variations in generics, but make sure the patient knows how to use them.

Fit dry eye patients for contact lenses only after symptoms subside. Any treatment with topical steroids must be completed before the fit. Be sure that the base curve, diameter and lens material allow for appropriate tear exchange. Patients should avoid overnight wear, and patients who wear their lenses more than 10 hours per day should make time to remove, clean and reinsert the lenses at some point. Recommend a frequent lens replacement schedule to reduce the risk of irritation from protein buildup, as well as more frequent follow-up visits.

CONCLUSION

Dry eye is already a prevalent condition but in all probability more Americans will suffer from the condition than ever before as Baby Boomers get older. As a result, ECPs will hear more patients complain about dry eyes. Baby Boomers grew up wearing contact lenses, and ECPs should anticipate helping them deal with dry eye effectively so they can continue enjoying the advantages of contact lenses. Lens materials are improving. There are solutions and artificial tears in the research pipeline to help dry eye patients achieve the comfort and convenience other contact lens wearers have come to expect.