NUTRITION AND VISION

By Linda Conlin, ABOC/NCLEC

Release Date: February 1, 2019

Expiration Date: December 1, 2021

Learning Objectives:

Upon completion of this program, the participant should:

- Review age-related eye diseases and how nutrients can aid in postponing and minimizing their effects.

- Learn the sources of eye health promoting nutrients.

- Learn about herbal supplements and their link to vision health.

- Understand patients' personal health and perceptions.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

Linda Conlin, ABOC/NCLEC

Credit Statement:

This course is a Technical Level II course approved for one (1) hour of CE credit by the National Contact Lens Examiners (NCLE).

We've all heard that "you are what you eat;" it could also be that "we see what we eat."

To understand the biological effects of nutrients on our visual system, we must first gain knowledge of eye anatomy and physiology, and learn how cells produce oxidants and subsequent oxidative damage. The effects of oxidation in the development of cataract, glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration will be explored. We will learn about how antioxidants and nutrients work, and the mechanisms through which they can delay onset, and/or reduce the effects of those diseases.

PHYSIOLOGY

When we look into today's nutrition and health, we hear quite a bit about antioxidants, but what are they? And if there are ANTIoxidants, then there must be oxidants. What are they?

OXIDANTS AND ANTIOXIDANTS

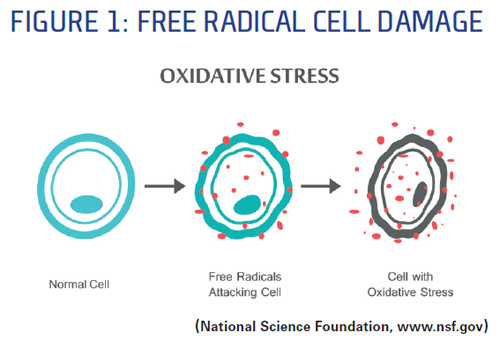

An antioxidant is a molecule capable of slowing or preventing the oxidation of another molecule. As for oxidation, we're all familiar with the oxidation of metal resulting in rust. So are our cells rusting? It's not quite the same. Oxidation is the process by which cells metabolize oxygen to produce energy. That's a good thing. In cells, as with rust, oxidants are the byproducts of oxidation. Largely as a result of external factors like UV exposure, smoking and diets high in fat and sugar, some of these oxidants are in the form of free radicals—not a good thing. Free radicals are molecules that contain unpaired electrons. They are highly reactive with cell structures to gain the missing electrons, causing oxidative damage to cells and proteins as illustrated in Fig. 1.

How do our bodies cope with the damage? Young cells can recognize and break down damaged proteins using protease enzymes. As we age, this damaged protein removal system diminishes. By donating electrons to free radicals, which neutralizes them and prevents them from causing harm, antioxidants help do the work that the cells are no longer efficient at doing to protect against damage from free radicals.

IMPACT ON VISION

Damage from oxidation plays a role in the development of cataract, glaucoma, agerelated macular degeneration and dry eye. Let's look at cataract first.

Cataract is an opacity of the crystalline lens resulting from the accumulation of damaged cell protein. Cataracts are classified by the location of the opacity, generally nuclear (central) or cortical (peripheral). Cataract extraction is the most common surgical procedure in the U.S. at more than 3.5 million procedures per year.

Lens oxidants are smoking, hard alcohol consumption, elevated levels of carbohydrates and fats, Body Mass Index (BMI) over 30 (calculated as: weight in pounds x 703/height in inches) and UV and blue light exposure.

Exposure to blue light, the region of the electromagnetic spectrum closest to UV, has been shown to exacerbate cataract development because of damage to cell proteins. Although the crystalline lens has naturally occurring substances that absorb blue light, exposure to blue light over time diminishes the lens' natural defense. Those naturally occurring substances are carotenoids, which are organic pigments ranging from yellow to red, and they function as antioxidants. Lutein and zeaxanthin are carotenoids that not only occur naturally in the crystalline lens, but are recommended as vision preserving supplements. People who have a diet rich in carotenoids have been shown to have an 81 percent decrease in the odds for posterior subcapsular cataract (which forms on the back of the lens beneath the lens capsule), however, diabetes increases the odds for posterior subcapsular cataract fourfold.

Lens antioxidants include vitamin C (more than 300 mg/day for 10 years), vitamin E, riboflavin, folate (naturally occurring folic acid) a-carotene, niacin, thiamin, lutein, zeaxanthin and protein. Antioxidants have been shown to protect against nuclear and cortical opacities especially in the elderly, and use of vitamin C supplements for more than 10 years was associated with 33 percent decreased odds for cortical cataract based on a UK study. What's more, people with diets rich in aor b-carotene, carotenoids that provide about 50 percent of the dietary recommendation for vitamin A, have been shown to have a decrease in the odds for cataracts, although it is still under study. As with vitamin C, people with diets rich in vitamin E for more than 10 years have been shown to have a decrease in the onset and progression of cataracts. This indicates that taking antioxidants isn't short term; it must be a continuous nutritional habit.

Let's take a look at glaucoma. Glaucoma isn't increased intraocular pressure in and of itself, it's the damage to the optic nerve caused by that pressure. It is possible to have elevated intraocular pressure without it being considered glaucoma. There are two forms of glaucoma: open angle, which is slow onset, painless, reduced drainage through trabecular meshwork, and closed angle, which is sudden onset and painful, where the iris is pushed forward and blocks the trabecular meshwork. (The trabecular meshwork is tissue located around the base of the cornea which drains aqueous fluid.)

While the connection between glaucoma and nutrition hasn't been firmly established, some evidence points that way. Several studies have shown decreased risk of glaucoma among people who consumed more vitamin A, folate, a-carotene, b-carotene, lutein and zeaxanthin (antioxidants). What's more, when neuronal cells such as those in the retina are damaged, they release glutamate which aids neural transmission, again, a good thing, but in excess kills the cell. The excess glutamate is also taken up by surrounding cells causing more damage and is a major cause of loss of retinal ganglion cells in glaucoma. Nutrition comes in because magnesium minimizes the damage from excess glutamate. Good food sources of magnesium are: whole wheat, spinach, quinoa, almonds, cashews, peanuts, dark chocolate, black beans, edamame and avocado. Reducing glutamate intake may help, too. Many processed foods contain glutamates, and monosodium glutamate (MSG) can be found in many fast foods and snack foods.

Next is age-related macular degeneration (AMD). There are two types of AMD: Dry AMD in which cellular debris (drusen) accumulates between the retina and the choroid, which supplies blood to the retina, and the retina becomes detached; and wet AMD in which blood vessels grow from the choroid behind the retina and can detach the retina. The macula contains organic pigment which is depleted by free radicals, but antioxidants (carotenoids) can build and maintain the thickness of the retinal pigment layer.

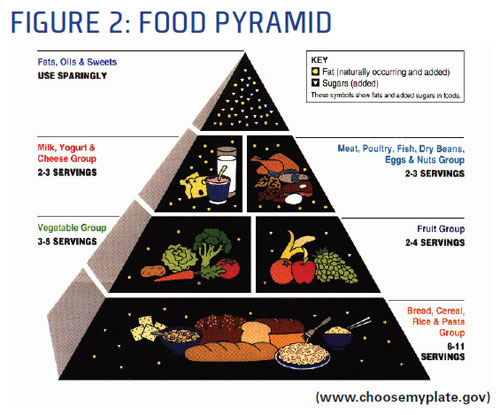

Here's more to the nutrition connection to AMD. An Australian study in conjunction with the Laboratory for Nutrition and Vision Research predicted that reducing the glycemic index 10 percent through decreased carbohydrate intake would reduce the risk for AMD by 20 percent. The glycemic index (GI) is a ranking of how quickly food is metabolized into glucose when digested. It compares available carbohydrates gram for gram in individual foods. Foods that are metabolized quickly have a higher GI, and foods that are metabolized more slowly have a lower GI. Foods with a lower GI are better because they are more slowly digested and absorbed, causing a lower and slower rise in blood glucose levels. We know that higher blood glucose levels, like those of diabetics, cause retinal damage. Vegetables, proteins and many dairy products have a lower GI, while fruits and starches are higher.

The National Eye Institute Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) showed that antioxidant supplements can reduce the risk of vision loss from advanced AMD by 25 to 30 percent, although less benefit was shown for preventing cataracts. The study also showed that the ability of lutein and zeaxanthin to absorb blue light helps to protect the retina and prevent free radical damage to the macula.

In 2001, the results of the AREDS study produced the AREDS formula for nutritional supplements to prevent or minimize eye disease. That formula consisted of:

- 500 milligrams (mg) of vitamin C

- 400 international units of vitamin E

- 15 mg b-carotene

- 80 mg zinc as zinc oxide

- 2 mg copper as cupric oxide

However, that formula was modified in 2006 to:

- 10 mg lutein

- 2 mg zeaxanthin

- 1,000 mg of omega-3 fatty acids (350 mg DHA and 650 mg EPA)

- No beta-carotene

- 25 mg zinc

As you can see, lutein and zeaxanthin replaced vitamins C and E, omega-3 fatty acids replaced copper, the amount of zinc was reduced, and b-carotene was eliminated. High levels of b-carotene were found to be associated with an increased incidence of lung cancer, especially in smokers, and high levels of zinc (the current recommended daily allowance is 8 mg) can result in abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and stomach irritation. Other possible symptoms include headache, irritability, fatigue and dizziness. High doses of zinc over a long period of time have more serious health consequences. Copper was eliminated from the AREDS formula when zinc was eliminated because excess intake of zinc reduces levels of copper, a necessary nutrient.

Riboflavin, vitamin B2, in addition to being a lens antioxidant, has been used in combination with UV-A light in collagen cross-linking to treat keratoconus. Cross-linking strengthens the bonds between the collagen fibers of the cornea, stabilizing the progression of keratoconus. But we thought UV exposure was damaging to the eye! While UV-A exposure results in stronger corneal fiber bonds, riboflavin has a dual function of acting as a photosensitizer to induce the physical cross linking of collagen, and it also absorbs the UV-A irradiation (90 percent), thereby preventing damage to deeper ocular structures.

SOURCES OF NUTRIENTS

How do we identify the nutrients that are most important to eye health including lutein, zeaxanthin, and vitamins A, C and E, and the sources of those nutrients from foods and supplements? What are the recommended daily allowances of each of those nutrients for vision health?

How do we identify the nutrients that are most important to eye health including lutein, zeaxanthin, and vitamins A, C and E, and the sources of those nutrients from foods and supplements? What are the recommended daily allowances of each of those nutrients for vision health?

Most nutrients are best obtained from foods instead of supplements, but we may not consume the variety of necessary nutrients on a regular basis. For example, to take in the 300 mg of vitamin C shown to reduce the risk of cataract would require eating four oranges daily—for at least 10 years! While not impossible, it is unlikely for most of us. Other fruits, such as grapefruit, papaya and cantaloupe are good sources of vitamin C, but also require several servings per day to reach the 300 mg goal.

An intake of 6 mg of lutein per day is a little more than half of what is recommended in the AREDS formula, but the average U.S. diet contains only 1.3 to 3 mg. Foods that provide the recommended amount of lutein are (for each one cup cooked) collard greens (15.4 mg), kale (20.5 mg), turnip greens (12.1 mg) and spinach (fresh cooked, 12.6 mg). Raw values differ, and in some cases, such as spinach, may be lower than the cooked values. Kale, collard greens and spinach all contain enough zeaxanthin in a single one-cup serving to meet the AREDS formula recommendation. Eggs are another good source of carotenoids and help increase absorption of those nutrients. A caution regarding leafy green vegetables, however: They also are a good source of iron, which is contraindicated for people who are taking blood thinners.

Food sources high in vitamin A include yellow fruits and vegetables such as apricots, cantaloupe, carrots and sweet potatoes, as well as leafy greens such as kale, collard greens, mustard greens and spinach. The U.S. Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for vitamin A is 700 to 900 micrograms (mcg). The good news is that one cup of cooked sweet potato provides 204 percent of the RDA.

Good food sources of vitamin E (RDA 15 mg) are almonds, sunflower seeds and peanuts, but as with other food sources of vitamins, two to five quarter cup servings of any one of them are needed to meet the RDA. Most of us won't consume enough from natural sources of these important nutrients, so it's a good idea to check with a physician about the best vitamin supplements based on individual nutritional needs.

So which food is the best source of nutrients for eye health? Most people will say carrots because mom said so, but while carrots are a great source of aand b-carotene, one vegetable is top for the most nutrients beneficial to eye health: spinach. It's the only food that contains both lutein and zeaxanthin, as well as being a good source of magnesium, vitamin A and aand b-carotene.

HERBAL SUPPLEMENTS

A nutrition for vision health conversation is not complete without a discussion of herbal supplements, their relationship to vision health, and how these products are regulated. Attendees will learn which of those supplements have been accepted as beneficial, and which have questionable efficacy. Discussion will also include the effects of water, alcoholic beverages, caffeine and marijuana on eye health.

Herbal supplements are alternative or complementary medicines. They are available over the counter and are not regulated in the same way as conventional drugs. As a result, recommended dosages and quality differ for the same product. Supplements may also contain substances other than the main ingredient. It's important to remember that "mega doses" of any vitamins and supplements should be avoided, and many may have negative interactions with prescription medications.

While we wouldn't recommend unproven herbal supplements to patients, it's important to know something about them. Patients may ask about them or already take them. The internet is full of sites offering "miracle cure" herbs and supplements that our patients may investigate, so we need to be prepared. Let's take a look at some of the alternative supplements that have made claims to benefit eye health.

Alcohol: The Laboratory for Nutrition and Vision Research found that while consumption of hard alcohol is associated with increased risk for nuclear and cortical opacities, moderate wine drinking decreases the risk, and it may also reduce the risk for AMD. There are some indications that two or fewer drinks per day may reduce glaucoma risk. However, it is important to note that the National Institute of Health (NIH) does not endorse alcohol consumption in any amount for any reason.

Bilberry: There's a legend about this close cousin to the blueberry. The story goes that World War II British Royal Air Force pilots reported improved night visual acuity and successfully hitting more targets after consuming bilberries. Animal studies have shown bilberries to reduce retinal inflammation, which might explain the possibility of improved night vision. The FDA has not approved bilberry supplements for the treatment of any medical condition.

Marijuana: As medical marijuana gained approval, many ophthalmologists received requests from their glaucoma patients for prescriptions. While marijuana consumption has been shown to reduce intraocular pressure (IOP) by 20 percent, it is only for short periods of time. An effective treatment would require many doses per day. Now that recreational marijuana by state is gaining approval, although still illegal under federal law, patients may be tempted to try it as a treatment or preventative for glaucoma. Non-intoxicating cannabis derivatives are being studied for possible reduction of IOP. Cannabidiol (CBD) oil is one derivative under study and has been found to lower IOP. It may also have some neuroprotective effects on retinal cells and may increase contrast sensitivity in low light.

Gingko biloba: Long touted for its ability to enhance memory, gingko biloba is a powerful antioxidant that increases ocular blood flow. This may help protect the optic nerve in glaucoma. It may, however, cause bleeding. It is also thought to protect against cell death induced by high glucose in the crystalline lens and so prevents early cataract. Caution: Gingko biloba can interact negatively with other medications such as anticoagulants, antidepressants and even ibuprofen.

Coleus forskohlii: Stimulates the ciliary epithelium, which produces the aqueous humor, to produce cyclic adenosine monophosphate, an intracellular "messenger," which decreases aqueous humor flow. In this way, it may reduce IOP and the risk of glaucoma. Rather than being taken internally, it is administered through eye drops. While coleus forskohlii has been shown to lower IOP in people without eye disease, it has not been tested on patients with glaucoma. Caution: Negative interactions include medications for high blood pressure, nitrates and anticoagulants.

Salvia miltiorrhiza: Also known as Red Sage or Chinese Sage, this plant is used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat glaucoma. Although it doesn't reduce IOP, it may protect the retinal ganglion cells from damage from increased pressure. Extreme caution should be exercised with this herb, as it exacerbates the effects of blood thinners and Digoxin, and side effects include drowsiness, dizziness, itching, upset stomach and undesirable bleeding.

Flaxseed oil: This oil provides essential Omega-3 fatty acids, and there is some early evidence that it may be as effective as doxycycline in treating dry eye and preventing dry eye after LASIK without the side effects. It may also help to protect nerve cells and prevent free radical formation thereby, oxidative stress. Caution: Flaxseed oil may slow blood clotting and should not be taken with anticoagulants.

Water: Water is a micronutrient (non-energy nutrient) needed to maintain all body processes. It can reduce the need for artificial tears. With a recommended intake of half gallon per day, it's likely that most people don't drink enough water to maintain proper hydration. Excessive water levels can exacerbate glaucoma, but that requires consuming half to 1 liter in 15 minutes.

Coffee: In addition to the pick-me-up we get from caffeine, scientists have identified approximately 1,000 antioxidants in unprocessed coffee beans and even more are a result of the roasting process. Researchers from Cornell University identified one antioxidant, chlorogenic acid (CGA) that may prevent retinal degeneration by preventing loss of oxygen to the retina. It's important to note that the study was done on mice. While more study on CGA is needed, coffee remains a potent source of antioxidants. Caution: Research has also shown that drinking three or more cups of coffee a day increases IOP a small amount. For people at risk of exfoliation glaucoma, a type of open angle glaucoma that results in characteristic deposits on the crystalline lens, the risk increased with that amount of coffee consumption, especially in women.

PATIENT PERCEPTIONS

In order to communicate the importance of nutritional effects on eye health, we must first assess the patient's personal habits relevant to general health, vision health care and contact lens wear. We must gather information from the patient regarding dietary habits and explore the patient perceptions of nutrition for eye health. Let's explore how we communicate nutrition information to patients. But first let's see what the data tells us about the prevailing perceptions of patients regarding nutrition and their eyes.

In a recent national survey of more than 4,000 people in Canada, 33 percent responded that both their overall health and diet were very good, yet other data indicated that approximately half of the population wasn't getting the recommended daily requirements of fruits and vegetables. Only about 25 percent of those surveyed reported being overweight, but national statistics indicate the real number is 59 percent. It seems that, in general, our perceptions about our own health and nutrition are skewed to the better.

More specifically, the American Optometric Association 2008 Eye-Q survey asked which food was best for eye health. Forty-eight percent of respondents chose carrots. Only 2 percent chose spinach, which we now know is correct.

In addition, more than 50 percent of individuals don't achieve the RDA for vitamin C, and more than 90 percent don't achieve the RDA for Vitamin E. We can then presume they aren't getting enough of the other nutrients critical to eye and vision health.

Diseases of the eye progress slowly through life, and many factors including genetics and environment are involved in addition to nutrition. As ECPs, we aren't nutritionists, but we can still take an interest in how nutrition affects our patients' eye health. We can take the "it can't hurt and it might help" approach in some cases. For example, before recommending lubricating drops for contact lens wearers, ask how much water they drink. The solution to their drying contact lenses may be as simple as drinking more water.

You can provide patients with information about nutrition and vision health from WebMD, the American Optometric Association, Prevent Blindness and the Ocular Wellness and Nutrition Society. If the patient history shows family members who have cataract, glaucoma or macular degeneration, why not ask if the patient is aware of the relationship between nutrition and eye disease? You can ask what constitutes a typical meal—breakfast, lunch, dinner—and if it sounds like they may not be getting the nutrients that would benefit them, recommend that they talk with their doctor. With better knowledge of the impact of nutrition on vision, you can make recommendations for a healthier diet and lifestyle. The benefits will go beyond vision to overall health.

By the way, what did you eat today? It's all about choices!