Joe Santinelli proudly displays the vintage edging

equipment

he donated to the Optical Heritage Museum

By Andrew Karp

In discussions of optical industry history, Arthur Lemay’s name doesn’t often come up. Unlike celebrated figures like Bernard Maitenaz, who invented the Varilux lens, or Noel Roscrow, Robert Graham and Rene Grandperret, who played key roles in the development of plastic lenses, or O.W. Coburn, who helped commercialize automated surface generators, Arthur Lemay is relatively unknown.

Joe Santinelli has made it his mission to change that. For the past 30 years Joe, the founder of lens finishing equipment maker, Santinelli International, has been waging a one-man campaign to get Arthur Lemay the belated recognition he fervently believes Lemay deserves.

Joe’s mission is driven by his sense of pride and personal loyalty. Arthur Lemay was Joe’s uncle. He gave Joe his start in the optical industry job in 1954, when Joe signed on as an apprentice at A. Lemay & Co., a New York-based developer and distributor of lens finishing equipment.

Dick Whitney (left) and Joe Santinelli discuss

how to display the Lemay Electromatic

and Diamaline edgers

Lemay has two claims to optical fame. One is the development of the Lemay Electromatic edger. The other is the development of the Diamaline Automatic Bevel Edger (more on that later). Here’s a description of the Lemay Electromatic and its impact on the optical industry that I wrote for L&T some years ago. Here is an excerpt:

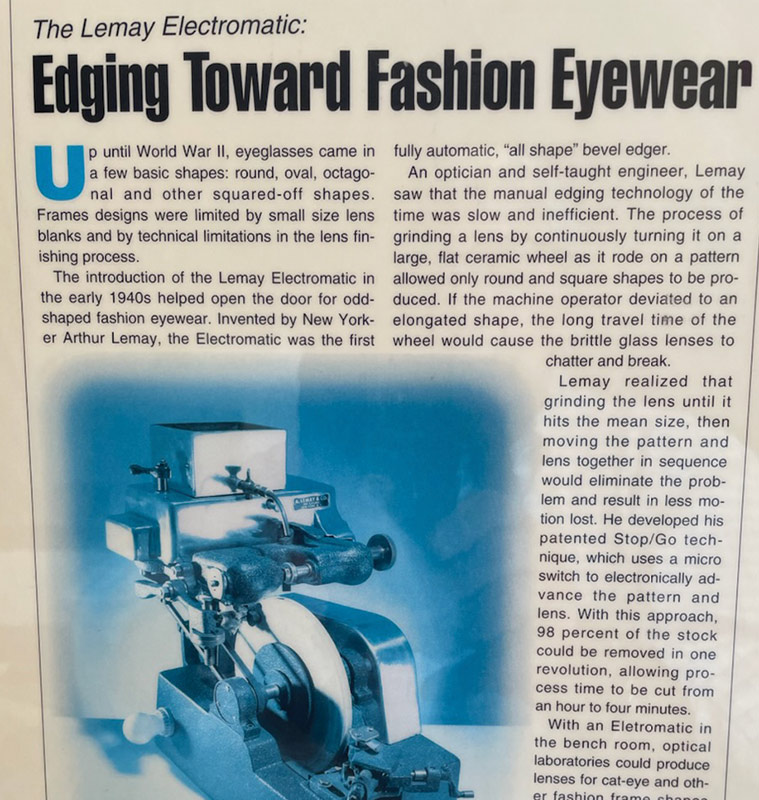

Up until World War II, eyeglasses came in a few basic shapes—round, oval, octagonal and other squared off shapes. Frame designs were limited by small size lens blanks and by technical limitations in the lens finishing process. The introduction of the Lemay Electromatic in the early 1940s helped open the door for odd-shaped fashion eyewear.

Invented by New Yorker Arthur Lemay, the Electromatic was the first fully automatic, “all shape” bevel edger. An optician and self-taught engineer, Lemay saw that the manual edging technology of the time was slow and inefficient.

The Lemay Diamaline was the first diamond bevel wheel. Introduced in 1955, it rapidly replaced the ceramic bevel wheel, facilitating the industry’s

conversion from glass to plastic lenses and

ushering in a new era in lens finishing.

The process of grinding a lens by continuously turning it on a large flat ceramic wheel as it rode on a pattern allowed only round and square shapes to be produced. If the machine operator deviated to an elongated shape, the long travel time of the wheel would cause the brittle glass lenses to shatter and break.

Lemay realized that grinding the lens until it hits the mean size, then moving the pattern and lens together in sequence would eliminate the problem and result in less motion loss. He developed his patented Stop/Go technique, which uses a microswitch to electronically advance the pattern and lens. With this approach, 98 percent of the stock could be removed in one revolution, allowing process time to be cut from an hour to four minutes. With an Electromatic in the bench room, optical laboratories could produce lenses for cat eye and other fashion frame shapes, which were soon to become popular.

Lemay and Co.’s next big product was the Diamaline Automatic Bevel Edger, which Joe helped design just a year after joining the company. The Diamaline was the first diamond bevel wheel. Introduced in 1955, it rapidly replaced the ceramic bevel wheel, facilitating the industry’s conversion from glass to plastic lenses and ushering in a new era in lens finishing. “All the big frame and lens manufacturers have really grown as a result of what Arthur Lemay did,” Joe says.

The Lemay Electromatic, the first fully automatic, “all shape” bevel edger, helped open the door for odd-shaped fashion eyewear

Joe owns an original Electromatic and a Diamaline, both of which he has had refurbished. Santinelli International displayed the machines at Vision Expo a few years ago, but then they were returned to storage. Since then, Joe had been searching for a permanent home for these two pieces of optical history. When he called me over the summer and asked if I had any ideas, I suggested he contact Dick Whitney, executive director of the Optical Heritage Museum in Southbridge, Mass. Located near the former headquarters of American Optical, the Museum is now owned and operated by Carl Zeiss.

Dick appreciated the historic value of the equipment and arranged for Joe to donate the edgers to the Museum. “I felt it was time to share this historical equipment with the industry and educate the industry about where we were and why we are here today,” says Joe. As he observed following a previous visit to the Museum, “There are many vintage frames on display there, along with vintage diagnostic equipment. However, the missing links are the Lemay-Santinelli equipment.”

In November, Joe, who at 93 is still quite active, drove from his Long Island, N.Y., home to Southbridge and delivered the 1939 Lemay ceramic bevel edger and 1959 Diamaline, both in mint condition, to the Museum. “As the executive director of the Zeiss-sponsored Optical Heritage Museum,

An article from Jobson’s

L&T magazine that

described the edgers and

their historical importance

I am very excited to announce that Joe Santinelli has arranged to have us display two first of a kind, historic edgers,” says Dick. “These units helped revolutionize how lenses were edged and led the way for more unique and fashionable lens shapes than had been routinely made prior to this.

“Joe personally delivered these units, and he and I set up a display prominently seen at the entrance,” Dick says. “The Museum has a vast collection of frames and lenses, but having this addition helps tell a more complete story of the evolution of spectacle eyewear in the 20th century.”

Over the course of his seven decades in optical, Joe Santinelli has cultivated a deep respect for the pioneers who, like Arthur Lemay, have “helped transform our industry from the technological dark ages into the modern age of lens fabricating,” as he wrote in a Vision Monday essay in 2006. He expressed concern that “too few in the optical industry today are aware of the pioneers whose past contributions paved the road in order for us to all share and enjoy today’s successes” and urged us “not to lose sight of our past.”

Now that his beloved edgers are in good hands at the Optical Heritage Museum, Joe can be assured that visitors will have an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the evolution of eyeglasses and the essential role these machines—which were cutting edge, both literally and figuratively—had in modernizing eyeglass production. ■

Note: This article grew out of a series of conversations between Joe Santinelli and myself over a 30-year period. It was originally published by 20/20’s affiliate, Vision Monday, in its online newsletter, VMail Weekend. –AK