By Christine Yeh

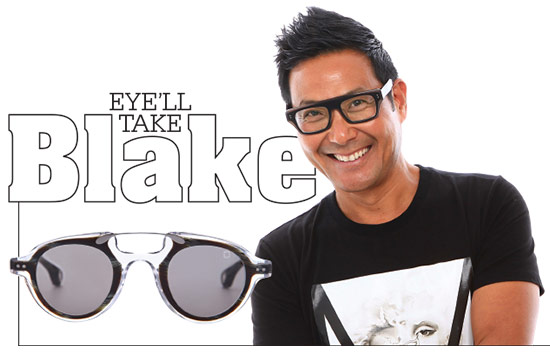

Behind every frame is a great face. Yes—the one who wears said frame. But it is also the face of the mastermind creating that frame. This was precisely 20/20’s mindset in 2000 when we debuted “Artist of the Frame,” an ongoing series featuring those who design eyewear for a living. And because eyewear styles and trends come and go (and come back eventually), it’s their talent and brains as the evolving force. As with any art form, it’s time to revisit some of these previously profiled designers. The most prominent example of this is award-winning designer Blake Kuwahara, our first featured profile. Sixteen years later, Kuwahara reaffirms his rightful title as an Artist of the Frame, setting the bar for true eyewear art. This is the story of Blake Kuwahara—personifying what an eyewear designer aspires to be.

It’s just after the new year on a cold winter morning when I call Blake Kuwahara to chat about his storied career. He had just returned home from Chicago, working with newly launched STATE Optical. But his time back home in Sausalito, Calif., is short-lived; later that morning he takes off again, this time to Asia for another project. As we spoke, Kuwahara was finishing packing and checking to make sure all was secure with his house. A car was arriving in a half hour to take him to the shuttle station to San Francisco International Airport. Not wanting to delay him, I worry we won’t have enough time for an interview. But Kuwahara calmly continues our conversation even while en route to the airport. I wasn’t the one traveling, but as someone who tends to stress about traveling (yes, I’m THAT person who has to be at the airport super early), I wonder how he is able to remain so calm and patient answering all my questions with detail and clarity while accomplishing multiple tasks. It’s clear this is the norm in the life of a celebrated designer, but as our conversation ensued, I would soon learn the serene aura projected by Kuwahara is innate to him, along with his sincere and humble nature.

It’s been over 25 years since Kuwahara began designing eyewear. He is no stranger to 20/20. In addition to being our first Artist of the Frame profile, Kuwahara also happens to be Editor-in-Chief James Spina’s first designer interview even before he took on the role of 20/20 EIC. And though Kuwahara’s name isn’t in every issue, his creative stamp has graced many pages in our magazine with the countless eyewear collections he has designed. But many would be surprised to hear designing eyewear was not initially on Kuwahara’s agenda. He was always interested in the arts and exposed to it since his childhood with both his grandmother and mother being artists. But Kuwahara followed a rigorous academic program in high school, specifically on the medical and science track. His aptitude in the sciences earned him a grant from NASA, with focused intention to pursue a science degree. “I felt it was a natural thing for me to get into,” explains Kuwahara. “Plus I think because of my parents—all Asian parents secretly want their kids to become doctors or lawyers and being a firstborn, it was natural for them as well,” he laughs good-naturedly. Coming from an Asian background myself, I’m all too familiar with this.

It’s been over 25 years since Kuwahara began designing eyewear. He is no stranger to 20/20. In addition to being our first Artist of the Frame profile, Kuwahara also happens to be Editor-in-Chief James Spina’s first designer interview even before he took on the role of 20/20 EIC. And though Kuwahara’s name isn’t in every issue, his creative stamp has graced many pages in our magazine with the countless eyewear collections he has designed. But many would be surprised to hear designing eyewear was not initially on Kuwahara’s agenda. He was always interested in the arts and exposed to it since his childhood with both his grandmother and mother being artists. But Kuwahara followed a rigorous academic program in high school, specifically on the medical and science track. His aptitude in the sciences earned him a grant from NASA, with focused intention to pursue a science degree. “I felt it was a natural thing for me to get into,” explains Kuwahara. “Plus I think because of my parents—all Asian parents secretly want their kids to become doctors or lawyers and being a firstborn, it was natural for them as well,” he laughs good-naturedly. Coming from an Asian background myself, I’m all too familiar with this.Upon receiving his undergraduate degree at UCLA studying psychobiology, Kuwahara considered all the science and medical-related career paths but being an MD or a dentist didn’t interest him. Since he worked part-time on weekends at an optometrist’s practice as an undergrad student, optometry had captured his interest. “I worked at this practice helping out with the front desk area, and I realized that this was the perfect blend of my interests—medical and science with a fashion component to it.” Kuwahara applied to UC Berkeley School of Optometry and got accepted. Concurrently interning at an interior design firm in Los Angeles, he was offered a full-time position after graduating from UCLA. Faced with the difficult decision of choosing between two fields he equally enjoyed, Kuwahara looked to his parents. “My parents being good Asian parents encouraged me that it would be silly not to attend optometry school. They reminded me that I can always pursue interior design down the road but attending Berkeley was NOT an opportunity I should pass up. So I took their advice.” It turned out to be probably the best advice they ever gave him.

Upon graduating with a doctorate in optometry at Berkeley, Kuwahara was recruited by Manhattan Beach Vision Group in LA. It was a busy practice with nine opticians and two other ODs, each with their own practice management responsibility. Kuwahara immediately began working there, overseeing the dispensary area, in charge of product assortment and frame buying. “Very quickly I found that I enjoyed being what we call the front of the house more than back of the house, being with the patient in the dark room,” he says. “And it was really some of the little things that should’ve occurred to me when I was in optometry school that made me question whether or not I was in the right place for myself.” Being in the dark room and the lack of scheduling flexibility in a very busy practice were among these “little” things, which would ultimately turn into bigger issues for him.

Kuwahara noticed an employment ad in the Los Angeles Times for an eyewear company called Wilshire Designs. The position was for a fashion forecaster, specifically seeking candidates who had an interest in fashion with an optical background. Convinced this was the perfect opportunity, Kuwahara applied, but not without some unanswered attempts. Eventually he nailed down an interview followed by a second interview, and to his surprise Wilshire owner Dick Haft offered him the position of creative director instead, putting him in charge of all product design for the company. “I was flabbergasted… I had no experience doing anything in terms of designing eyewear. I was taking a chance on them, and they were taking a chance on me. Dick, who is still a close friend and mentor told me, ‘I can teach you the mechanics of eyewear design, but I can’t teach someone the aesthetics—design sensibility and color, etc. But I think you have that and the rest… we’ll see.” Haft had the foresight this would be Kuwahara’s destined path as eyewear designer. “Here I am—30-something years later. I was very lucky to have this amazing opportunity.”

The first brand Kuwahara worked on at Wilshire was Liz Claiborne. It was the early ’90s, and Liz Claiborne was the most prominent womenswear designer at the time. But Kuwahara had a burning desire to also design his own eyewear collection, something with his design sensibility. Wilshire honored that wish, and Kata Eyewear was born. Kata is Japanese for shape and form, and the collection debuted as eyewear trends were shifting from high-fashion plastics to minimalist metals. Gaia, the first collection from Kata took direction from natural elements, with subtle shapes and classic designs that were artful yet wearable. After Wilshire Designs was sold in 2002, Kuwahara took his talent to Rem Eyewear, who was looking to realign its designer portfolio. As creative director at Rem, he oversaw product development, as well as creative direction on the marketing side. As a member of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), Kuwahara had ties to menswear designer John Varvatos and womenswear designer Carolina Herrara, both looking for license partners for eyewear collections. This led to the formation of Rem’s Base Curve, a luxury division, which began the manufacture and distribution of John Varvatos Eyewear and Carolina Herrara Eyewear. Jones New York and Lucky Brand were also licenses established under Kuwahara’s tenure at Rem.

With his own eyewear collection and multiple major designer licenses under his belt, Kuwahara took his product and design knowledge and marketing experience to the next level with a new venture. “One of the great takeaways for me personally from working at Wilshire and Rem was really looking at how products and brands were brought to market. In a lot of eyewear companies, different departments work in silos—product works in one silo, marketing works in another, sales works in yet another—and that creates a lot of dysfunction. My goal was to take a very integrated approach so product, marketing and sales all worked together.” In 2009, he launched Focus Group West, a collaborative design collective with this objective in mind, providing comprehensive design services to the optical and fashion industries. With a team of eyewear designers, architects, graphic designers, a public relations consultant and a team based in Hong Kong, the company takes on everything from discreet projects such as designer logos and displays to more comprehensive undertakings where it creates the brand, establishes the brand ID and the brand platform, and designs the product, displays, merchandising and collateral, and brings it to market. Eyewear design and marketing is a main component of the business but Focus Group West also has a roster of prominent apparel designers and commercial brands including Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Giorgio Armani, Alexander Wang and J Crew, to name a few. “My role with our apparel clients is to help them be better at targeting in on their customers’ wants and needs, to help them better interpret the seasonal trends based on their own brand interpretation.” Kuwahara contends working on the apparel side provides great insight to the eyewear side. “Eyewear is technically an accessory; we accessorize fashion and apparel so having this entry point to the apparel industry gives me direct insight into what’s happening in terms of trends and fashion and colors.” The company also specializes in architectural and interior design services for optometric practices and optical retail dispensaries.

But let’s get back to eyewear design. Focus Group West boasts a long list of clients on the eyewear side, working with eyewear companies with licensed brands or creating proprietary collections. With the exception of a few that are publicly known, Kuwahara declines to mention names, respecting privacy and for competitive reasons. His most recent projects include Kingsley Rowe Eyewear and Adlens Focuss, a collection heavily driven by technology with the use of Adlens’ fluid-filled lens technology that changes the power of the lenses. This particular project was especially interesting for Kuwahara since it enabled him to balance design aesthetics with technology, resulting in the engineering of a product that marries art and science.

EYEducation: An Artist Gives Back

Blake Kuwahara may have made a career out of designing eyewear, but this Artist of the Frame has not forgotten his optometry roots. Kuwahara remains active with his alma mater UC Berkeley School of Optometry, working closely with them to mentor students. Recently the optometrist-turned-designer was keynote speaker at the school for first-year optometry students, where he spoke on the options available after graduation—

going into private practice, an HMO setting, research, etc. Although Kuwahara himself did not stay long in the field, he felt it was important to remind students that in order to be happy and successful in their careers, they need to “sweat the small stuff” because sometimes a small thing can make a big impact. In his case, the “small thing” for him was a turning point in his career.

Another active endeavor for Kuwahara is his involvement with the newly formed Eyewear Designers of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (edCFDA), a working group of the CFDA for eyewear designers. He states that one of their missions is to help mentor people who want to get into eyewear on the design side. “We have no entry points—no schools, no formal internships. It’s really hard to get into the eyewear design field, and that’s one of the things we want to do with the edCFDA, is actually formalize some of this so people who do have an interest, whether or not they’re industrial designers, opticians, people in fashion or accessory designers who want to get in the field, they at least have a resource to do that.” Kuwahara also hopes to use the edCFDA as a vehicle to assist optometrists on the retail side of the business. “Being a former optometrist, there are things that are really not emphasized when you’re in optometry school, you learn all the medical side of things but we never had any classes or instructions on how to set up a business, what your retail space should look like, how you should organize your dispensary, how you should purchase and buy. None of those things are taught to the students, and we want to provide more education on that.” —CY

Kuwahara’s most recent collaboration is something 20/20 continues heralding—the launch of STATE Optical, a new collection designed and made in the USA via Europa International. “Europa was looking to open a factory to produce a collection that was solely made in America, which sounded extremely intriguing, the fact that anybody would take up such a huge undertaking like that takes a lot of courage and confidence to be able to get that off the ground.” For Kuwahara, this was an important project not only on a personal level, but for the industry by bringing manufacturing back strong to the U.S. “Europa was very generous in bringing me into the project and allowing me to be a part of that creative process, so I was not only involved in discussions about the product but also about the branding, the logo, the overall brand concept.” Kuwahara worked closely with STATE’s creative agency, STATE Optical CEO and Europa vice president Scott Shapiro, Europa president Jerry Wolowicz, and Marc Franchi and Jason Stanley of Frieze Frames, who joined forces with Europa in setting up and running the new factory and working on the manufacturing to get STATE operational. “I worked really closely with Mark and Jason to make sure what was expressed in two dimensions came out in three dimensions when we actually made the product, and that the product and marketing synced up. Together with everyone else, it was a very tight team and a very interactive one because everybody had to work together to get this across the finish line.”

Barely halfway through our conversation, I ask Kuwahara that BIG question. After 25-plus years of designing, what took him so long to design an eyewear collection under his own name? In the most humble and somewhat shy and reserved manner, he answers: “That’s a good question… I think… fear?” This surprises me but Kuwahara adds the timing simply hadn’t been right for his own collection, but mainly for unselfish reasons. “With Focus Group West, it was ideal that we started right at the height of the economic crisis in 2008 or 2009—we were very lucky that we had the support of quite a few companies and people that saw a need for this in the marketplace at the time. Ironically, the timing worked out because a lot of companies were concerned about fails and were looking for answers, and one of the things we brought to the table was bringing them a design resource they can rely on. At that time, I really didn’t think about starting my own collection because I was being able to express myself creatively through other companies’ brands and projects. When you design for other people, whether or not it’s under a license or proprietary brands, you’re still restricted to the design tenets of that brand, and it may not always match your own design sensibilities. But at the same time, when you have a brand that’s under your own name, there’s a lot of responsibilities and a lot of pressure, not necessarily from a design standpoint, but I think more from a sales and marketing standpoint, it leaves you very vulnerable because you’re very exposed. And I went through that with Kata. It was really an amazing experience but it really does start to take its toll.”

Barely halfway through our conversation, I ask Kuwahara that BIG question. After 25-plus years of designing, what took him so long to design an eyewear collection under his own name? In the most humble and somewhat shy and reserved manner, he answers: “That’s a good question… I think… fear?” This surprises me but Kuwahara adds the timing simply hadn’t been right for his own collection, but mainly for unselfish reasons. “With Focus Group West, it was ideal that we started right at the height of the economic crisis in 2008 or 2009—we were very lucky that we had the support of quite a few companies and people that saw a need for this in the marketplace at the time. Ironically, the timing worked out because a lot of companies were concerned about fails and were looking for answers, and one of the things we brought to the table was bringing them a design resource they can rely on. At that time, I really didn’t think about starting my own collection because I was being able to express myself creatively through other companies’ brands and projects. When you design for other people, whether or not it’s under a license or proprietary brands, you’re still restricted to the design tenets of that brand, and it may not always match your own design sensibilities. But at the same time, when you have a brand that’s under your own name, there’s a lot of responsibilities and a lot of pressure, not necessarily from a design standpoint, but I think more from a sales and marketing standpoint, it leaves you very vulnerable because you’re very exposed. And I went through that with Kata. It was really an amazing experience but it really does start to take its toll.” But the calling for his own label finally came, and Kuwahara knew he was ready. Coincidentally around the same time, fellow design counterparts Bevel Eyewear approached him about a collaboration through Focus Group West. “I try to be very careful in terms of making sure that when we do projects, there’s no conflict of interest with regard to working on a brand that might be in the competitor space as one of our other clients. I was starting to think about designing my own collection, and I had put some initial thoughts and designs down, and because Bevel is in the high-end boutique market, the collection I wanted to do would be in that same space, so I felt it would be appropriate for me to disclose that and let them know that I was thinking about doing my own collection, and that it might be in the same competitor space as Bevel.” Kuwahara thought it would be the end of the conversation but instead it was actually the beginning of a new partnership. Bevel wanted to hear more and was instantly interested in being a part of the project. “For me, one of the things that was really the biggest deterrent was managing the back end and sort of the business of the business, setting up the infrastructure, computer systems, warehousing, sales organization, etc. I know the product and the marketing, I feel comfortable because that’s what I do. But the others take a lot of financial resources and the skill set that I really don’t have. But the Bevel guys brought that to the table because they already have their own company, their own offices and their own sales force. It really was an idea and a concept, and one prototype, and that’s how we got started.” The two sides formed Fade to Grey, a distributing company for Kuwahara’s collection, sharing offices with Bevel’s distributing company. The two also share the same sales force domestically.

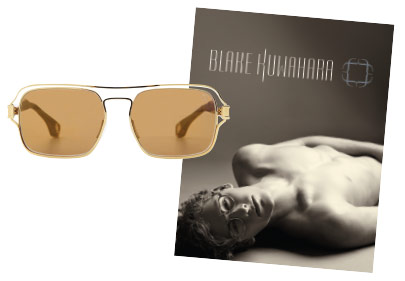

The debut of Blake Kuwahara Eyewear was worth the wait. Kuwahara presented a mind-blowing collection with a never-before-seen concept in eyewear, a “frame within a frame” design that was born from a dinner conversation with a friend, who was a photographer active in the arts. “She was lamenting that she had a really difficult time finding frames that suit her design sensibility and aesthetics. And I had a prototype on, and she said, ‘I want something like what you have on!’ And she mentioned that frames tend to be very classic in a way or they’re very directional in terms of color and shape, which I find to be true. And finding a collection that takes into account both the aesthetics and also the wearability sometimes is missing in our marketplace. I wanted to be able to sort of blend the idea of something artful yet wearable, something that had two separate aesthetics.” Achieving this was a challenge. Kuwahara found his answer while shopping one day. “I saw this antique Chinese elm stool that was encapsulated in a clear lucite block, and I thought, how amazing is this that we have something that’s very familiar on the inside, and you encase it in something fresh and put it into a whole new context, and that has a whole new interpretation—a different look and feel to it. I wondered if there was a way we can do that with eyewear, create two different frames in one frame. And that was the challenge I brought to the factory and from that, the concept was realized.” As unique as the concept is, it’s not an easy one to accomplish, because two plastics have very different physical properties due to the way they are manufactured, whether it’s block acetate being used or extruded acetate. And because different colors react differently, it is also a challenge figuring out dimensionally exactly what the frames have to be in order to have a perfect match since they both have different shrinkage rates. “There’s a lot of R&D that went into the project and a lot of back and forth, and essentially the frames are two frames that have to be made because we have an outer frame and an inner frame. And because it’s very challenging to get a frame perfect, our scrap rate is about 50 percent, about half of what we make we have to throw away. So essentially, almost four frames go into making one frame. Even with designing—it’s like designing two frames because you have to design an outside frame and an inside frame, and then you have to choose the colors for both so there’s a lot of work that goes into just one frame. It’s kind of doubling my workload,” he jokes. Since arriving to market after only one year, the new collection has received accolades with terrific support from the North American market, followed by a healthy penetration into the European markets. For the time being, Kuwahara plans on continuing the frame within a frame concept but expanding into other materials. “I think with eyewear collections, it’s important to maintain a sense of continuity and consistency but still evolve. That’s kind of where we are—because we’re so new, and I’m still telling a story of the frame within a frame, I think there are a lot of different expressions of that that are left to be explored. I’m still playing with that interplay between different kinds of plastics, and I’m integrating more metal into the plastic combination, which adds another layer of complication from an engineering standpoint but it also adds a whole different look and feel.”

With over 25 years of design experience, one would think it isn’t difficult for Kuwahara to explain how and where he finds design inspiration. But as is often the case for designers when asked what fuels their artistic talents, Kuwahara errs on the side of modesty. “That’s a good question… because that’s your insight, right? But I think it’s a hard one for designers to answer and for me in particular... though I don’t know why I have a hard time with it!” he says laughingly. “I think like anything, and this sounds extremely selfish, it starts off with—I want to design something I want to wear. And something that inspires me is something that inspires all my purchases, whether or not I’m purchasing something for my house, clothes, etc., it has to speak to me in the way that I think is unique. I appreciate things that have design integrity… things that are well-designed but that are simply designed and that are expressive. That can come in a lot of forms, it can come in the form of architecture, in the form of graphic design, in the form of furniture, etc. We live in such a visual world, and anything that resonates with that kind of design tenet is an inspiration to me.” Kuwahara often finds such things at flea markets he frequents no matter where his travels take him. “I’m always looking for things that have soul or interesting texture or combination of materials, and it can be very eclectic; my house is very eclectic in that regard but I think everything sort of hangs together because there is that common thread where the pieces are simple, but there is something inherent in them that is expressive. It’s not about how much can you add but how can you take away and still have a perfect form, and when I see that, it is inspirational because you want to be able to do that in your own world, and my world right now is eyewear. And that’s motivating, to see what’s out there.”

With over 25 years of design experience, one would think it isn’t difficult for Kuwahara to explain how and where he finds design inspiration. But as is often the case for designers when asked what fuels their artistic talents, Kuwahara errs on the side of modesty. “That’s a good question… because that’s your insight, right? But I think it’s a hard one for designers to answer and for me in particular... though I don’t know why I have a hard time with it!” he says laughingly. “I think like anything, and this sounds extremely selfish, it starts off with—I want to design something I want to wear. And something that inspires me is something that inspires all my purchases, whether or not I’m purchasing something for my house, clothes, etc., it has to speak to me in the way that I think is unique. I appreciate things that have design integrity… things that are well-designed but that are simply designed and that are expressive. That can come in a lot of forms, it can come in the form of architecture, in the form of graphic design, in the form of furniture, etc. We live in such a visual world, and anything that resonates with that kind of design tenet is an inspiration to me.” Kuwahara often finds such things at flea markets he frequents no matter where his travels take him. “I’m always looking for things that have soul or interesting texture or combination of materials, and it can be very eclectic; my house is very eclectic in that regard but I think everything sort of hangs together because there is that common thread where the pieces are simple, but there is something inherent in them that is expressive. It’s not about how much can you add but how can you take away and still have a perfect form, and when I see that, it is inspirational because you want to be able to do that in your own world, and my world right now is eyewear. And that’s motivating, to see what’s out there.”Kuwahara’s Japanese heritage also plays a factor in his design. “When I’m in Japan, I do feel like I’m in my aesthetic home. When you look at the typical Japanese architecture with very pure and simple lines, and you go to retail stores, things have a sense of placement and that Zen philosophy. And think of the packaging—they have the most amazing packaging, and the graphic design, again there’s a sense of simplicity to it.” The Japanese concept of “wabi-sabi,” an aesthetic that defines the beauty of an object by its imperfections also speaks to Kuwahara’s design sensibilities. “The simplicity of Japanese design married with the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, which is the humbleness of the object itself, show inherent beauty and that imperfections can create inherent beauty in an object. It’s like not having a perfectly symmetrical vase, but the fact that you can see the artist’s thumbprint or the way that it’s fired or there’s an irregularity in the firing, that in and of itself creates the beauty—that is also what I find to be very interesting, particularly when I’m at the flea markets. I look for that soul in an object because it adds character to a product.”

With his career spanning over three decades, Kuwahara has seen firsthand the evolution of eyewear style. He began designing in the early ’90s when the trend toward eyewear was more about understated minimalism. Since then, some trends have come and gone, and some have resurged and are here to stay, but Kuwahara believes that we’re at a time where the trend is no trend. “Compared to the past, today when you go to a well-curated optical boutique, you’re going to find thick frames, you’re going to find thin frames, you’re going to find plastic, but also metals. It’s not so one-directional anymore. The same thing with apparel and fashion, you see that same diversity.” The challenge is to stay ahead of the curve, without going too far ahead. Kuwahara relies partially on intuition to get a sense of where trends are headed and what people are looking for, as well as using himself as a consumer to get an idea of what he responds to and what he doesn’t respond to. “Consumers are very savvy, and sometimes they’re ahead of the retailers in terms of what they find is acceptable. Sometimes our stumbling block is the retailer—the consumer is more ready for fashion and fresh ideas. I also feel that people are now looking for things that have an artisanal sensibility to it—you see it already with how we eat, like with farm to table cooking—we want fresh ingredients. We’re looking for things that are handcrafted, and eyewear is one of those things that used to be thought of either as only a medical device or commodity, yet there’s this growing movement for things that are uniquely made in limited numbers and are not so common and can’t be found at chain stores.” A good example of this is Kuwahara’s latest project, a collaboration with fellow eyewear designers l.a.Eyeworks (see sidebar).

Artful Co-Workers

Artful Co-Workers

Whether it’s in fashion or retailing, brand and designer collaborations are becoming more and more commonplace. But they are still rather new when it comes to eyewear, and Blake Kuwahara is hoping to change that. “Design can often be a solitary discipline unlike music, which is inherently more collaborative. But it’s the interaction of these musicians and the fusion of their different influences and styles that can result in something totally unexpected and amazing; think Lady Gaga and Tony Bennett!” The designer recently partnered with Gai Gehardi and Barbara McReynolds of l.a.Eyeworks to launch a capsule collection that is literally “a mash-up” of the two designers’ sensibilities. The collection consists of two ophthalmic frame designs “Two Noons” and “Two Rays,” created using Kuwahara’s frame within a frame concept. The frame styles feature two of l.a.Eyeworks’ most iconic shapes on the inside, encapsulated by Kuwahara’s frames on the outside. “Gai and Barbara are my eyewear design heroes, so to be able to design this collection with them is really a dream come true. Although our individual ‘looks’ are very different, I think this capsule collection really does reflect both our aesthetic sensibilities. We like to call our ‘children’ bilingual since they speak both our (design) languages!” Gehardi, who co-founded and co-designs l.a.Eyeworks with McReynolds, adds: “We set out to distill and combine the essence of both of our brands as an adventure in optical alchemy.”

Along with Kuwahara, Gehardi is on the edCFDA board. “One of the goals of the edCFDA is to further the awareness of our category by eyewear designers working together through educational, promotional and philanthropic initiatives. What better way to show our collective efforts than to design a collection together!” says Kuwahara. Handcrafted in Japan, both styles are available in four distinct acetate combinations. The collection will be sold as a limited edition eight-piece set, with only 100 kits available. A combo cleaning cloth made with the two designers’ cleaning cloths sewn together accompanies each frame along with a protective custom case. A portion of the sale of each frame will benefit Las Familias del Pueblo and the work of Alice Callaghan on behalf of underserved populations in the historic core of Los Angeles. —CY

At this point in our conversation, Kuwahara is on the shuttle and almost at the airport. As our conversation continued, he has already taken the taxi to the airport shuttle, rode the shuttle and arrived at the airport. There were parts of our conversation where a lot of shuffling around and background noise can be heard, yet he somehow managed to continue our chat without the call getting cut off, never missing a beat.

As our conversation nears the end, I ask Kuwahara what’s next for him. “Moving forward, it’s about continuing this journey, continuing to build the brand. We’re only a year into the marketplace but it’s been a great first year, and it’s now about building markets where we are looking to enter, for example Japan and Korea. We’re also looking to continue collaborating with other companies, both eyewear companies and with my own line, as well with projects for Focus Group West. My efforts aren’t completely focused on my own line, I’m still working on other eyewear collections, which I think is healthy and good—it helps to give me different perspectives and not become so insular.” Even with such a colorful career and countless projects, he remains humble, genuine and open-minded. Kuwahara proves creativity and artistry can originate from any discipline, regardless of where or how you get your start. Perhaps this is why he is also dedicated to mentoring optometry students and those who are interested in pursuing eyewear design. Without doubt in years to come, a new generation of “Blakes” in the making will crop up—future eyewear artisans cultivated from this Kuwahara legacy. And we’re counting on them being our next Artists of the Frame. ■