TAKING THE MEASURE OF DIGITAL CENTRATION SYSTEMS

PART 1: WHAT DOES "BETTER" MEAN?

By Jeff Hopkins

Release Date: August 1, 2017

Expiration Date: December 31, 2020

Learning Objectives:

Upon completion of this program, the participant should be able to:

- Understand the need for greater accuracy and consistency in eyeglass lens fitting measurements.

- Understand the tangible and intangible benefits of digital measuring systems.

- Know the range of systems available in terms of platforms and capabilities, and how the operator interacts with them.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

Jeff Hopkins, is marketing director for GsRx in Scottsdale, Ariz., and a journalist with an extensive background in the optical industry.

Credit Statement:

This course is approved for one (1) hour of CE credit by the American Board of Opticianry (ABO). Technical Level 1 Course SWJH666-1

It was Lord Kelvin, the great British physicist and thermometer enthusiast who said, “To measure is to know. If you cannot measure it, you cannot improve it.” Perhaps this is obvious, but it sounds more impressive when it’s said by a great scientist. (In the interest of full disclosure, he also said “Heavier than air flying machines are impossible,” which is obviously wrong. But having been forced to fly coast-to-coast in an economy-class middle seat, I don’t think he was that far off.)

By now you’ve most likely recognized the application of Kelvin’s statement to eyeglasses. From the prescription itself to fitting the eyewear, it’s all about measurement. Precise PD and fitting height values are crucial to progressive lens performance, and additional measurements, done with high accuracy, can make the visual experience even better.

Which brings us to devices for measuring patients. Since the virtues of the ruler are already well-established, we will move directly to the high-tech variety, which are sometimes called “digital centration systems.” They come with varying capabilities and range from freestanding units to tablet-based. But they all fill one important role: taking the measurements your lab needs to create the best possible eyewear for your patient.

Given that there have long been ways of taking patient measurements that didn’t require batteries or a wall socket, why would you want a digital device? Let’s explore the question.

Given that there have long been ways of taking patient measurements that didn’t require batteries or a wall socket, why would you want a digital device? Let’s explore the question.

ACCURACY

Using a ruler to take PD and fit height measurements is effective but not ideally precise. The more sophisticated lenses become, the greater the precision needed to get the best visual performance. And no matter how good you are at taking the measurements, there are limitations to how accurately a ruler can measure, and how consistent the results can be when different opticians use them.

An internal study by Carl Zeiss Vision showed that the average variance among measurements taken by different opticians using a ruler was almost 3 mm. Pupilometers are much more accurate, but different models showed measurement variance ranging from 1.2 to almost 3 mm. By contrast, a recent European study of four different digital measurement systems showed an average variance of 0.09 to 0.24 mm, depending on the device used. (“Comparison of PD Measuring Devices,” opticiansonline.net, Feb. 12, 2010)

Are a couple of millimeters here and there really going to cause problems? Yes. A 2-mm centration error can reduce the size of the binocular field of view by 25 percent (“i.Terminal by ZEISS Frequently Asked Questions,” Carl Zeiss Vision, 2007). Progressive performance is highly dependent on the pupil being positioned the right distance above the corridor (good distance vision and comfortable access to the near) and aligned with the corridor (comfortable movement through the channel as the eyes converge for near vision.) These factors, in turn, depend on precise monocular PD and fit-height measurements. Errors in these measurements are among the leading causes of redos.

Several other factors contribute to the superior accuracy provided by digital measurement devices:

Several other factors contribute to the superior accuracy provided by digital measurement devices:

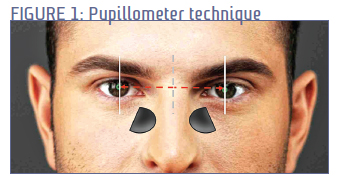

Corneal reflection vs. pupil center: Some devices measure horizontal centration based on a light reflection off the cornea, rather than pupil center. The difference is that the distance between corneal reflections remains constant, while the distance between pupil centers changes as the pupil gets larger (this is because the iris opens asymmetrically.) However, there is disagreement as to which approach is most appropriate.

PD measured with patient wearing frame: From a fitting perspective, monocular PD can change based on how the frame is positioned on the face. After the nosepads are adjusted to provide a comfortable fit, the fit of the frame bridge may not align precisely with the center of the nose. From a centration perspective, the center of the frame is the more accurate measurement. With a pupilometer, this refinement can’t be captured. But because they take PD measurements with the patient wearing his or her frame choice, digital measuring devices can achieve the most accurate measurement for real-life wearing conditions. Of course, it’s very important that the frame be adjusted properly before the measurements are taken.

Head rotation and tilt: No matter how much you encourage a patient to assume a natural posture, they won’t necessarily be looking perfectly straight at the camera. The head may be tilted slightly (usually upward) or turned slightly. Some systems will automatically correct for these factors. In the case of patients who have a permanent asymmetrical head or neck position (a condition known as torticollis) or have suffered a neck injury that has changed the way they hold their heads, this correction feature can be turned off.

ADDITIONAL MEASUREMENTS—POSITION OF WEAR

If everyone had the same facial features and wore the same frame, predetermined measurements of the wearing positions of the frame would work perfectly. (Of course, we’d all have to wear nametags.) But the way a particular frame sits in front of a particular face is unique. Before digital surfacing was available, position of wear measurements didn’t matter, because we couldn’t do anything with them. Lens manufacturers designed their lenses for an average vertex distance, pantoscopic tilt and frame wrap.

If everyone had the same facial features and wore the same frame, predetermined measurements of the wearing positions of the frame would work perfectly. (Of course, we’d all have to wear nametags.) But the way a particular frame sits in front of a particular face is unique. Before digital surfacing was available, position of wear measurements didn’t matter, because we couldn’t do anything with them. Lens manufacturers designed their lenses for an average vertex distance, pantoscopic tilt and frame wrap.

But who’s average? Even if there were average people, I don’t think they’d admit to it. The fact is, any difference between the average vertex distance, pantoscopic tilt and frame wrap, and the patient’s specific measurements can affect visual performance, in terms of the width of the viewing zones, their alignment with the eye and the effective lens power perceived by the wearer.

It’s possible to take these additional measurements using manual tools, but the process is cumbersome and won’t provide the kind of precision that is really the point of compensating the lens design for the way the patient wears it. A digital device can do it quickly, easily and accurately.

EFFICIENCY

A digital device may not take measurements as fast as the old tried-and-true approach, but there are several ways that it can help the office run smoothly.

We’ve already discussed how inaccurate measurements can lead to redos. Taking lens measurements is something of an art; it can take time to learn how to do it well. Staff turnover being what it is, it’s likely that at any given time there will be a dispenser in the office with relatively little experience in measuring. A digital device will deliver consistent results with some training and a little practice. That can eliminate one source of unacceptable lens performance.

Plus, most devices can communicate directly with the office’s practice management software. The key measurements can automatically go into the lab order, with no need to manually input them and no possibility of transcription errors.

DEMONSTRATION AND TRY-ON

Before there were digital measuring systems, there were digital try-on systems. These allowed patients to see themselves in several different frames side-by-side and get opinions from friends and family. Sometimes these can be emailed instantly for quick feedback. Since digital devices have the same essential elements (camera and screen) as try-on systems, it only makes sense to combine both functions.

But most measuring devices don’t just serve as a frame consultation tool: They also use graphics, including animations and wearer’s-eye views to help guide the patient through a discussion of lenses, coatings and treatments. Take it from a long-time copywriter: To explain to a patient why a lens needs AR coating or why customized progressives work better than the standard variety, using words alone does not produce good results. Side-by-side images or animations that compare, for example, the viewing zones of customized versus semi-finished lenses, are far more persuasive in showing patients the advantages of the premium technology you offer. Some also incorporate patient questionnaires, so recommendations can be made based on the patient’s particular lifestyle needs.

PATIENT PRESENTATION

We’ve been talking about the tangible benefits of a digital measurement system. Now let’s look at the intangible benefits, which relates to how your patients view the eyecare solutions you provide.

A premium digital progressive lens can cost the patient a lot of money, and they don’t get so see what they’ve paid for until the eyewear arrives from the lab. It’s important for patients to have confidence that they’re getting a sophisticated, customized device that is precisely attuned to the factors that make their vision unique. And when it comes to confidence, what is seen is often more important than what is heard. Leaving the importance of accurate measurements aside, how well do a ruler and a felt pen fit with a high-tech digital optical device?

I am not trying to slam rulers here, but they don’t exactly represent new technology—the oldest preserved measuring stick is roughly 4,500 years old. And frankly, it hasn’t improved much over that time: An ivory ruler discovered at the Mohano-daro excavation site in Pakistan is accurately subdivided into increments of 0.005 inches. By comparison, the felt-tip marking pen is brand-spanking new, dating back only to 1910. Sure, both represent proven technology, but what message do they send?

Suppose you have the chance to fly on a commercial airplane with the latest in propulsion, navigation and avionics technology. But then you notice that the only way to board is via a ladder propped against the plane. And it’s not a nice aluminum ladder, either: It’s a Fred Flintstone-style ladder made of sticks. Now you’re starting to wonder if this is really the latest in aviation technology, or is it actually powered by pterodactyls attached to the wings? How does that affect your confidence in the plane’s ability to get you where you’re going in one piece?

This is, of course, an extreme example— the sort of thing that never occurs unless you’re flying Spirit Air. But the point is this: A patient can’t look at the lens and see what’s different about it. But you can show them that a lot of precision and specific information about them goes into making it.

In addition to demonstrating the technology that goes into a precision lens, this also conveys a message about your practice. What patients see, hear and experience during their appointment is by far the most convincing way of expressing what you stand for.

There is another element to this. Over 40 percent of practices now have a digital measurement device in their office, and you don’t want to be the last in your market to have it. It’s not exactly a matter of status, like when I bought a brand new ride-on mower because all of my neighbors had one (the fact that my lawn is landscaped with white rocks just shows you how far I’m willing to go to keep up with the Joneses). You’re not trying to impress your colleagues: You’re trying to impress your patients. These devices are now common enough that some of your patients may have been measured by one before, and you don’t want the best measurement technology to be conspicuous by its absence in your office.

DIGITAL MEASUREMENT DEVICE TYPES AND CAPABILITIES

I’m tempted to say that digital measurement systems come in all shapes and sizes, but let’s face it: nothing comes in all shapes and sizes. Digital measurement devices come in two basic forms: fixed (floor-standing or table) and mobile (usually tablet-based).

Floor-standing models make the biggest statement (literally) in your practice, because they’re relatively large and impressive looking, and patients may have never seen one before. As such, they can be a good conversation starter—some practitioners have said they’d seen people walk into practices just to find out what it was.

Typically, these devices can be automatically raised and lowered as needed to accommodate very tall people as well as those who can only be measured while sitting. Because they can be connected to the office network, the photos and demonstration features can be used anywhere in the office.

On the downside, floor-standing units will cost more, with prices that can run into five figures. They may also require professional installation and will definitely require some dedicated floor space in your optical, which isn’t always easy to find.

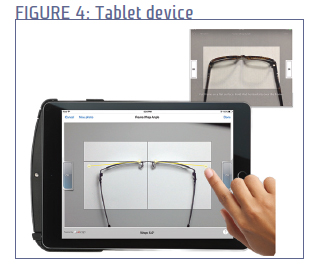

MOBILE/TABLET-BASED

As digital centration platforms, tablets are becoming more and more popular (just as they are becoming more and more popular for other activities). It’s easy to see why— they don’t take up any floor or table space, and the measurements can be taken almost anywhere in the office. For standard tablets, the measurement system is often an app that can simply be downloaded, while some manufacturers use a proprietary device as a platform. Some of these are sold for a flat price, while others require a monthly usage fee.

As digital centration platforms, tablets are becoming more and more popular (just as they are becoming more and more popular for other activities). It’s easy to see why— they don’t take up any floor or table space, and the measurements can be taken almost anywhere in the office. For standard tablets, the measurement system is often an app that can simply be downloaded, while some manufacturers use a proprietary device as a platform. Some of these are sold for a flat price, while others require a monthly usage fee.

There is a downside to this platform as well. Since the devices are small, there’s always a possibility that somebody can walk out with one. And they won’t make the strong impression on the patient that a floor model would. Let’s face it: While they’re certainly high-tech, the days when people would ooh and aah over a tablet are long gone. Patients are likely to see them as less special.

The two types are often very similar in function, and some manufacturers offer both versions. Generally, the tablet-based units will be more convenient and less expensive, while the floor-standing models show that your practice means business when it comes to technology.

OPERATION

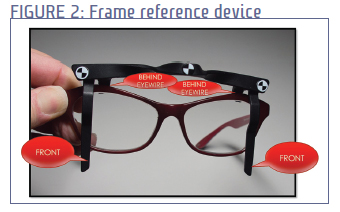

Preparation: Measurements are acquired through hi-res photographs. Most systems require two photographs, front and side, to take all the measurements. PD, fit height and face wrap are measured using the head on shot, while the side view captures pantoscopic tilt and vertex distance. A few systems use two cameras so all measurements can be captured at the same time. Of course, this can only be done using a freestanding system, but at least one mobile system also takes all fitting and position-of-wear measurements with just one head-on photo.

Most systems employ some type of attachment or clip that is placed around the frame once the frame has been fit. The clip has points of reference both across the front and on the temple. This allows the system to calculate the exact distance between the camera and the frame, which in turn allows all the fitting measurements to be taken with high precision. Since all measurements are taken as the lens is worn, the frame must be carefully adjusted and fit before the photos are taken. (I know I’ve said this before, but it’s important enough to repeat. I bet I’ll say it again in Part 2 of this seminar, which I’ve just given myself an excuse to plug.)

Floor-standing units can be positioned such that the camera is aligned to the eyes to avoid parallax error. The device will indicate when this has been achieved. In the case of tablets, it may not be possible for the optician to hold it directly at eye-level, but at least some units can compensate for this.

Image Processing: The work is not done when the photos are taken; some effort is usually required by the operator to assure that the device correctly identifies all the important elements. This may include putting a box shape around the frame and lens to assure that the precise frame dimensions are captured, placing a circle around the pupil and marking the outer contour of the eye for precise vertex measurement. Most of this is done by means of mouse-dragging and clicking, skills which are pretty much universal by now.

AND THEN…

The completed measurements go into the practice management system and then the lab, where all those measurements are translated into completed eyewear that you will put on the happy face of your patient. And it’s made possible by the right measurements, precisely taken, all of which confirms that Lord Kelvin knew a thing or two.

All that’s left to be done is do some shopping and select the best system for your practice, right? Not quite. As with fitness club memberships, just shelling out the money doesn’t deliver any benefit (well, the fitness club membership may make you feel good about yourself for a couple of weeks.) Effective use of the measurement system requires that the optical staff is on board with it, they are confident in the accuracy of the measurements, and their use of it is habitual. There’s a lot to say about that—another hour’s worth of CE, in fact. So watch this space for Part II, which will be full of surprises (for me, anyway, because I haven’t written it yet.) If you’re lucky, I may tell you more about Lord Kelvin. And if you’re even luckier, I won’t.