Never Be Screw Loose

A Beginner's Guide to Screw Replacement and Repair

By Preston Fassel, BS

Release Date: September 1, 2014

Expiration Date: December 31, 2017

Learning Objectives:

To update the ECP on changes and adoption practices for a lens material that is capable of being the overall lens platform including:

- Identify the different types of eyeglass hinges as well as their advantages and disadvantages.

- Learn the proper procedures for different screw repair/replacement scenarios.

- Understand the proper use of tools for screw replacement/repair.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

Preston Fassel is an optician in the Houston, Texas area. His interests are in the history of eyewear and all things vintage. He writes for The Opticians Handbook and 20/20 Magazine, and has also been featured in Rue Morgue magazine, where he is a recurrent reviewer of horror and sciencefiction DVDs.

Preston Fassel is an optician in the Houston, Texas area. His interests are in the history of eyewear and all things vintage. He writes for The Opticians Handbook and 20/20 Magazine, and has also been featured in Rue Morgue magazine, where he is a recurrent reviewer of horror and sciencefiction DVDs.

Credit Statement:

This course is approved for one (1) hour of CE credit by the American Board of Opticianry (ABO). Course SWJH535

In the world of optical repair, perhaps the most common problem encountered is that of a loose or missing screw. While adjustments are reliant upon a variety of factors, from patient comfort to the malleability of a given frame, repairing a hinge requires precision in the form of the appropriate type of screw and the appropriate tools to replace or repair it with. The tiniest component of a pair of eyeglass frames, screws can often pose the biggest problem of all—from finding a replacement to simply handling screws. This CE course provides some guidance on the art and mastery of screw repair and replacement.

TEMPLES AND HINGES

Before examining screws themselves, it is important to understand how screws are utilized in frames and temples. There are three types of temples we will discuss: skull (or standard), spring and hingeless.

Standard hinges (or skull temples) are the oldest temples in use. Similar to the hinges found on doors, skull temples are composed of interlocking barrels attached both to the frame and to the temple; originally a post but now a screw, the screw is inserted through the barrels, threading them together and allowing the temple to move freely.

Standard hinges can be found on frames from virtually every manufacturer. Because they require less hardware than spring hinges, and are therefore available in many qualities, many less expensive frames will feature standard hinges. However, a well-made, high quality standard hinge is as durable and effective as a spring hinge.

Spring hinges, also called "flex hinges," are hinges in which a small mechanism is attached to the temple piece containing a tiny spring. This spring allows the temple pieces to "flex" outward, giving it both better resistance against wear and tear, and increasing comfort for the wearer by conforming to his or her head.

Hingeless frames are a relatively new type of frame in which the temple itself curves around the wearer's head, with no screw or hinge to open or shut the temple arms. This type of temple is largely found on rimless glasses and often made of titanium. As these types of temples do not utilize screws, they will not be discussed in this course. It is worth noting, however, that due to their relative newness to the market, they will be the least encountered type of hinge, and in the event of breakage, require replacement or soldering equipment for titanium in order to repair.

A BARREL OF LAUGHS

As noted above, interlocking barrels characterize standard hinges. Generally speaking, the more barrels to be found on a pair of glasses, the more durable they are, and the less likely that a screw will fall out or break. Higher quality frames will more often than not employ a larger number of barrels, while middle and lower quality frames will have fewer. The current industry standard is three: two mounted to the frame and the third on the end of the temple. Most spring hinge frames on the market today have a standard three-barrel construction, though some manufacturers do produce spring hinges with more.

As noted above, interlocking barrels characterize standard hinges. Generally speaking, the more barrels to be found on a pair of glasses, the more durable they are, and the less likely that a screw will fall out or break. Higher quality frames will more often than not employ a larger number of barrels, while middle and lower quality frames will have fewer. The current industry standard is three: two mounted to the frame and the third on the end of the temple. Most spring hinge frames on the market today have a standard three-barrel construction, though some manufacturers do produce spring hinges with more.

Adjusting for pantoscopic tilt gets more difficult as the number of barrels increases. Three-barrel hinges allow significant adjusting, seven-barrel hinges require very little. To add tilt to a seven-barrel hinge, an old plier called a duckbill is helpful to angle the barrels individually, and a zyl or metal file is needed to change the angle of the butt end of the temple. Note, however, in the photo that this frame has a set of front barrels on the frame front that are different lengths, longer on top and shorter on the bottom to allow the correct pan-toscopic angle.

BATTLE OF THE HINGES

Newcomers to opticianry will discover a very heated and passionate debate over the efficiency, durability and desirability of hinge type. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages, and various opticians will have different viewpoints, affected by factors from how long they have been opticians to personal experience with different hinge types.

Generally speaking, the optician community seems to favor standard hinges. They are more often than not the first type of hinge that most opticians have had experience with and are also the most easily to repair. In the event of damage or breakage, one must simply insert a new screw to make the glasses functional once more. Additionally, since screws are a readily available commodity, one rarely runs the risk of not having the supplies on hand to make repairs. This is also the design preferred by many high-end frame manufacturers, not only for its time-proven efficiency, but also because a multiple-barrel standard hinge design lends itself to high durability, therefore giving the product a better reputation as a solid piece of manufacturing. As such, there is a close association in optics between standard hinges and high-quality frames. However, frames with standard hinges come with what some might view as drawbacks: They require more and specific adjustment in order to not only comfortably conform to the wearer's head, but also to ensure that they do not slip off when the wearer is looking down or engaged in a physical activity.

Standard hinge frames must also be of a relatively close size to the wearer's head to fit properly: Too large, and they will not be able to be adjusted to stay in place. Too small, and the temples will squeeze the wearer's head, potentially causing pain and discomfort. Often, frame measurements will also include the distance between barrel screws. This is an indication of frame width and can be correlated directly with face width though not commonly used.

Spring hinges, conversely, are more often preferred by patients and will often be requested by name. Because they require few adjustments, spring hinge frames tend to fit most patients "out of the box." Similarly, many patients enjoy the subtle tension created against their heads by the resistance of the spring, which gives a sense of extra security. Because of the flex of the spring, patients for whom the frame would normally be too small, without it gouging into his or her temples and causing pain, can wear spring hinge frames. Also, just as opticians link high-quality frames with multi-barrel standard hinges, many consumers link low-quality frames with low-barrel standard hinges.

However, spring hinges also have several downsides: Though they can stand up well to wear-and-tear, they are significantly more difficult to repair than standard hinges and require the use of special supplies. Even if an optician has the necessary tools and supplies on hand, this can still prove to be a difficult and time-consuming process, and depending on the extent of damage to the hinge, repairs may not be possible at all. Additionally, while the design for spring hinges is relatively standard across the industry, some manufacturers have their own variations, which may make them more difficult to repair or even require custom parts from the manufacturer, a rare instance when dealing with standard hinges.

As you continue your career in optician-ry, you will encounter multiple viewpoints from patients as well as fellow opticians as to which hinge type is superior. My survey of opticians suggests that they generally prefer standard hinges while patients generally prefer spring hinges. Although you may ultimately develop a preference for one over the other based upon your own experience, it is ultimately most important to consider the patient's needs and desires. Explaining the various advantages and disadvantages to the patient will allow him or her to come to his or her own informed decision regarding which type of hinge is best.

NOT SCREWING UP

In making frame repairs, you will nominally encounter two types of screws: standard screws and Snap-Its. Of course, there are differences between eyewire, temple and nosepad screws.

In making frame repairs, you will nominally encounter two types of screws: standard screws and Snap-Its. Of course, there are differences between eyewire, temple and nosepad screws.

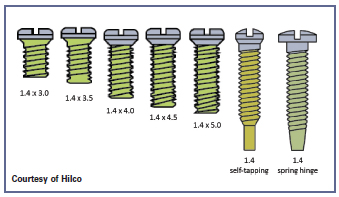

Standard screws are of the exact variety you have probably used in various hardware projects, except much, much tinier. They come in a variety of shapes and sizes, measured in millimeters. They are measured according to thread size, shaft diameter and length, with the thread size listed first, then the shaft diameter and finally the length. For example, a screw with a thread size of 2.5 mm, a shaft diameter of 1.3 mm, and a length of 9.6 mm would be listed as such: 2.5 x 1.3 x 9.6.

As with screws applied in any other area, eyeglass hinge screws come in both Phillips and flathead varieties; there is no real standardization according to manufacturer or frame type. The majority of frames require screws that are 1.4 mm in diameter, with some thinner wire frames using 1.2 mm screws. As we will discuss in a moment, thread size and shaft diameter are more important than shaft length in replacing screws.

Snap-Its are unique screws that have a long, thin, easily broken sliver of metal attached to the base of the screw which can be used as a guide to lead the screw through the barrels. Although useful for individuals who have a difficult time aligning a screw, their best application is in the repair of spring hinges.

THE RIGHT TOOL FOR THE JOB

While frame repair really can be as simple as popping a screw into place, there are situations which can prove more difficult, and tools which can greatly aid in the process.

DETERMINING SCREW SIZE

In the event that an unusual screw size is called for, finding the proper screw is easiest when the screw needing replacement is brought in by the patient. Often, patients will salvage the screw themselves and bring it in, lacking the proper optical tools to replace it themselves. In other instances, the screw may still be partially attached to the frame, needing either tightening or replacement due to worn threads. In either event, a device called a Screw Checker can be used to determine the right size for the job. A Screw Checker is a sheet of cardboard or metal, which has been drilled through with a variety of holes, each accompanied by a measurement. By inserting the screw into holes, it is possible to determine the proper diameter for the job.

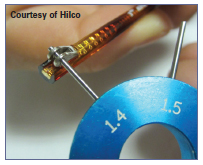

In the event that the screw is completely missing, you can determine the right gauge using a Screw and Hole Gauge. A Screw and Hole Gauge is a small wheel with various sized "spokes" that are inserted into the empty barrels of a pair of glasses until the spoke slides in snugly, giving you the proper screw diameter.

RE-LENGTHENING

As mentioned above, diameter is more important than length in replacing screws; as long as the screw is long enough, it can be resized. In many instances, using a longer than necessary screw may even be beneficial to the patient if it sticks out just slightly: If it is not long enough to pose a hazard to the patient, a longer than necessary screw can provide extra stability and help to keep it in place. If you need to shorten a screw, you will require a pair of wire cutters as well as a tool called a screwhead file. A screwhead file is a cylindrical tool similar in appearance to a screwdriver with a small, round file at the tip for precision filing. First, use the wire cutters to snip the screw down to an appropriate length. Then, use the screwhead file to smooth the sharpened edge down. Re-cut and re-file as necessary.

BROKEN SCREWS

In some instances, a screwhead may completely break off of the screw, leaving a section of it stuck inside of the barrels with no means for removal. This happens when screws are tightened too much, and the threads lock in the barrel while the portion below the head continues to turn until it twists and breaks. In this event, the use of a screw extractor is required. There are two types of screw extractors currently available: drill or pressure extractors. Drill screw extractors are long, thin cylinders of metal with tiny teeth at the end which grip the shaft of the broken screw and allow it to be removed through a standard screw rotating motion. Pressure extractors are a new type of extractor vaguely resembling a guillotine: The bar rels are lined up with a pin, which is then driven down onto the screw, breaking the threads, forcing it out.

BIG HEART, BIG HANDS: SCREW HANDLING AND MALE OPTICIANS

BIG HEART, BIG HANDS: SCREW HANDLING AND MALE OPTICIANS

Many opticians with large or larger than average hands will often have difficulty in handling screws. This can make screw replacement particularly frustrating. In order to more easily handle and insert screws, use a magnetized pair of bent snipe nose pliers in order to lift and insert the screws; the curved nose of the pliers will aid in visibility when inserting the screw and leaves enough a point to allow for easily manipulating the screw around the barrels.

IT'S A SNAP: SPRING HINGE REPAIR

As we have already discussed, spring hinges are more difficult to repair than standard hinges and are most easily fixed with a Snap-It screw.

When a spring hinge screw is lost or breaks, the internal spring contracts, placing the holes out of alignment with the frame front barrels. In order to make the frame usable again, the spring must be forced back into place while also bringing the barrels into alignment for replacing the screw. This is an often difficult process, as the misaligned screw more often than not prevents the optician from re-aligning the barrels for screw insertion. Sometimes, the spring hinge has been broken or it comes out of its housing; in this situation, repair is impossible. However, in the event that the frame is salvageable, Snap-Its are the best course of action.

The long, thin sliver of metal at the base of the screw will help to bring the spring, as well as the barrels, back into alignment. Simply align the barrels as best you can, keeping the temple in a "closed" position. Then, insert the Snap-It through the barrels, guiding it with the snap-off base. Once the threads have come into position, screw it into place. Once the screw is firmly in place, snap off the bottom of the screw. If the frame is salvageable, the temple should stay in place and become functional again.

The long, thin sliver of metal at the base of the screw will help to bring the spring, as well as the barrels, back into alignment. Simply align the barrels as best you can, keeping the temple in a "closed" position. Then, insert the Snap-It through the barrels, guiding it with the snap-off base. Once the threads have come into position, screw it into place. Once the screw is firmly in place, snap off the bottom of the screw. If the frame is salvageable, the temple should stay in place and become functional again.

If the proper tools are on hand, and one has sufficient experience, another option is soldering the temple barrel and its extension into the spring housing. This is a process that should not be undertaken without sufficient training, experience and a hands-on knowledge of soldering tools and procedures.

DON'T SCREW UP!

Over the course of your career as an optician, you will have to replace an untold number of screws in a variety of frame types. This can often be a difficult process, and one during which clumsy or inexperienced hands may break the frame, leading to patient conflict. Understanding the intricacies of screw replacement and repair—along with practice, practice, practice—will help you in fine-tuning your skills and becoming a repair whiz.