The increasing popularity of multifocal and accommodative intraocular lenses has brought with it a host of new challenges for surgeons and practices. Most practices now use extensive patient selection protocols to weed out individuals who are more likely to have trouble adjusting to these lenses, but challenges aplenty still remain. These include increased patient sensitivity to formerly minor visual problems; patients making unhappy comparisons between their eyes when one has been done but not the other; deciding how and when to correct residual refractive error; deciding how long to wait between the first eye and the second, especially if the patient isn't happy with the first eye; deciding when a lens exchange is the best option; and dealing with a small but significant number of unhappy patients.

To help shed light on these and other issues, we asked a number of experienced practitioners to share their insights and strategies for managing these patients once the first eye has been implanted.

Correcting Residual Error

In traditional cataract surgery, it's rare to have a patient be unhappy with the outcome, even when only one eye has been completed. But given the unique nature of presbyopic IOLs, dealing with a patient who has mixed feelings—or worse—is a fairly common occurrence.

When a patient is unhappy after one or both eyes are implanted, the first thing the surgeon has to do is identify the source of the problem. "Most of the time, dissatisfaction is the result of refractive error, not adaptation trouble," says John Vukich, MD, assistant clinical professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and surgical director of the Davis Duehr Dean Center for Refractive Surgery in Madison, Wis. "Generally, a residual error that wouldn't bother a monofocal lens implant cataract patient can be intolerable for a multifocal patient, so you have to be willing to correct small amounts of astigmatism or spherocylindrical mismatch."

R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, FACS, founder and medical director of Wallace Eye Surgery in

Dr. Wallace says that if it's clear that the refraction is stable but is unacceptable to the patient, he may resort to several different options. "If the problem is astigmatism only, we typically perform LRIs," he explains. "We could do the same thing with LASIK, of course, but since dry eye is an issue for these patients, we try to avoid a treatment that requires lifting a corneal flap. LASIK is also a much more expensive option, accompanied by greater risk.

"Another option is conductive keratoplasty, particularly if the problem is hyperopic," he continues. "CK is also helpful for astigmatism. Or, if the problem is a low amount of myopia, we may do a mini-RK. This is a good option when the problem is only in one eye after both eyes are done, and the patient is comparing them."

Another approach is simply to exchange one or both lenses. Richard Mackool, MD, PC, director of the Mackool Eye Institute and

"That may sound like heresy to everybody else," he continues, "but because I've had great success exchanging IOLs, that's what I would do. These patients signed up to have the right implant. They probably did not sign up to have an implant and then LASIK."

Dr. Mackool wonders whether the limited number of explanted lenses claimed by some surgeons is not at least partly the result of being uncomfortable with lens exchange. "IOL exchange today is like phacoemulsification was 30 years ago," he says. "Everybody was afraid to do it, because no one had done it much. IOL exchange is a lot easier to do than phaco. But relatively few surgeons have exchanged any IOLs, and no one has clearly elucidated the steps and techniques." [For more on Dr. Mackool's lens exchanging strategies, see "Extending the Time Limit for Lens Exchange."]

Other Sources of Trouble

In addition to residual refractive error, our surgeons say they look for dry eye, posterior capsule opacification, cystoid macular edema, ocular surface problems, pupil diameter and centering of the lens.

• Dry eye. "Dry eye is a big problem with multifocal lens patients, particularly for females and anyone who has had a history of dry eye," says Dr. Wallace. "Small changes in quality of vision can be very bothersome to these patients. Dry eye affects the quality of the corneal surface, making the optics not as good as they should be. Once we do surgery and use medications that have certain types of preservatives, a dry-eye problem often materializes—or an existing problem becomes worse for a while—even after the patient stops using the drops. That caught us by surprise, because it hasn't been a big issue with monofocal patients." He notes that with treatment, any uptick in the dry-eye problem goes back to normal.

• Posterior capsular opacification. "The issue with PCO," says Paul Dougherty, MD, medical director of Dougherty Laser Vision in Los Angeles, Camarillo and Santa Barbara, Calif., "is that if you think it's contributing to the patient's visual complaint and you do a capsulotomy, it's much more risky to do a lens exchange should the patient still dislike the lens. For that reason I tell the patient, 'If we break the posterior capsule, you bought it.' Of course, this makes it important to decide whether the complaint is primarily related to the lens or to the capsule."

Dr. Wallace notes that when PCO is an issue for a multifocal lens patient, he often has to perform a YAG capsulotomy earlier than he would with a monofocal lens patient. "Because not as much light is getting through for distance or near as you would get with a pair of glasses, these patients notice the vision interference early on—especially near vision problems," he explains. "So we'll do YAG laser sooner than we would normally with a monofocal lens."

• Pupil diameter. Dr. Mackool observes that this can be problematic for a multifocal patient, especially with the ReStor and ReZoom lenses. "If the patient has an accommodative pupil diameter that's bigger than 2.5 mm, he may not read well with a ReStor lens," he explains. "If the pupil is wider than this, too many light rays are focused for distance. This begins to bleach out or give a ghost image to the reading image. On the other hand, patients with a small pupil may read poorly with a ReZoom lens."

Dr. Mackool says his practice measures all patients' pupils before surgery, in both ambient and dim light, and also when the patient is trying to read. "We call the latter measurement 'accommodative pupil diameter,' " he says. "I've had several ReStor patients referred to me because they were unable to read well, and their accommodative pupil diameter turned out to be 3.5 mm or so. Everything else looked fine. I put a drop of pilocarpine 0.5% or 1% in their eye, and 25 minutes later they were reading fine.

"Some patients have no trouble using drops—possibly several times a day—to adjust their pupil size," he says. "Fortunately, if the patient is willing to use this option, after many months or in some cases a couple of years, the pupil will remain smaller on its own. We tell patients to use the drops for a few months and then stop every month for a day or two to see if they still need them."

• Pupil centration. Dr. Vukich notes that it's important to make sure the lens is centered on the pupil. "Some patients may have an eccentric pupil," he adds, "but this is the exception rather than the rule."

Managing Patient Reactions

Even when any physical or medical issues have been handled, implanting one lens at a time has forced practices to deal with patients' reactions to having only one eye altered for some period of time. Even patients who will ultimately be satisfied when both eyes are done may be disconcerted—or angry—during this interval.

Many surgeons deal with this by impressing the patient (both before and after the first surgery) with the idea that both eyes must be done before the results can be fairly evaluated. "Patients who have had their first eye taken care of tend to be underwhelmed on day one," admits Dr. Vukich, noting that for some patients the untreated eye may seem superior to the implanted eye. "For this to go smoothly, you have to have good rapport with the patient, the patient has to trust your judgment, and your explanation has to make sense," he notes.

"I tell patients that it's not a matter of one eye being good or bad, it's just that they're different," he says. "I use the analogy of having glasses with one photo-grey lens and one clear; you'd always notice the difference. Neither lens color is bad, but the difference would create dissatisfaction."

Dr. Wallace agrees. "This can be a tough time," he says. "You have to stay in open communication with the patient. You have to get him to understand that things are likely to improve. Patients know they don't have the knowledge and experience that we have, so it becomes an issue of trusting us to do the right thing."

How Long to Wait?

Because the interval between eyes is problematic, surgeons have to decide how long to wait before implanting a second lens—or doing a lens exchange. Dr. Wallace says the amount of time he waits before implanting the second eye varies, but is usually two to three weeks after the first eye is done. "You don't want to wait too long because some of these patients are very imbalanced between the two eyes," he says. "In that situation, they're not going to be happy until the second eye is treated.

"On the other hand," he continues, "the reason to wait two or three weeks is that the refraction in the first eye will be more stable, and that helps us more accurately calculate the IOL power needed for the second eye. We'll have a better idea of how the patient heals, which we can then take into account in our second eye power calculations, and we'll have a better idea of whether the second eye needs an adjustment so the combination meets the patient's overall visual needs."

"Moving ahead does require a leap of faith from both surgeon and patient if side effects are an issue," agrees Elizabeth A. Davis, MD, FACS, assistant clinical professor at the

Not every surgeon is in a hurry to do the second eye when the patient is dismayed, however. "Actually, the advisability of doing this depends on the issues the patient is having," says Dr. Mackool. "If the problem is anisometropia, where the two eyes can't work together because of different refractions, you can be comfortable going ahead. But if the complaint is about quality of vision or severe nocturnal symptoms—which happens about 3 percent of the time with my ReStor lens patients—there's no way to be sure the problem will improve if you proceed with the second eye.

"I want the patient to be happy with the first eye before I do the second eye," he continues. "I don't want a patient to say, 'Yeah, now they're equal—they're both crummy.' It's extremely unusual, but I've had patients who were very unhappy with their vision at all distances with a ReSTOR, ReZoom or Crystalens, and it didn't get better, no matter how long I followed them. If the second eye had received the same IOL, the patient would have been extremely unhappy and would be justified questioning the decision to do the second eye. Because I'm comfortable explanting an IOL for at least several months after surgery, I'm willing to wait before deciding how to proceed."

In some cases, exchanging a presbyopic for a different technology may be the only workable option. We asked our surgeons how they would handle making this decision.

"I'm sure different practices will have different ideas about this," says Dr. Vukich. "There's a fine balance between telling patients to wait and try to habituate, or talking them into the second eye in terms of it being the best option for them. My personal guidelines are, if at the end of six weeks the patient has not become comfortable with the decision to have the second eye done, I'd want to do an exchange by the end of three months. This has largely to do with ease of extricating the lens from the capsular bag."

"If four to six weeks have gone by and the only problem seems to be the lens optics, I'd consider doing a lens exchange," agrees Dr. Dougherty. "But I'd give the patient a minimum of a month or two to neuroadapt before I'd even consider an exchange."

The Unhappy Patient Factor

All of the surgeons we spoke to agreed that despite their best efforts, some patients will be unhappy. "Careful patient selection pays off after surgery, but you won't get 100 percent happy patients," says Dr. Dougherty. "Every ophthalmologist wants his patients to be happy, so it's a huge disappointment when they're not. My happy patients do outnumber the unhappy ones by a good margin or I wouldn't be doing this procedure, but there are patients who have issues."

Dr. Davis agrees. "A certain number of patients, despite your best efforts, will still be unhappy because it's impossible to describe to the patient beforehand what her vision will be like," she says. "And it's not just glare and haloes; it might be that quality of their vision is substandard. I have some very ecstatic patients who think that this is the best thing since sliced bread, but some others aren't as happy as they thought they would be. That's the nature of the beast. We're asking the patient to accept a compromise."

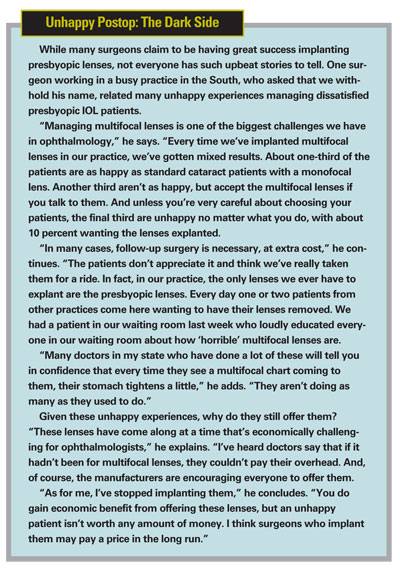

Dr. Vukich notes that this has been true in clinical studies as well. "When you look at the clinical trials for ReZoom and ReStor, about 5 percent of the patients were dissatisfied after binocular implantation on the subjective surveys," he points out. "If you do 20 of these a week, you may be generating one patient a week who is dissatisfied. These patients tend to come back more frequently, and they don't go away.

"In effect," he continues, "managing patient expectations and dissatisfied patients is the key to growing your practice with these implants. It doesn't take long to develop a small but vocal subset of unhappy patients. They can make all the difference to your practice because they'll tell everyone who will listen. Clearly you don't want to have dissatisfied patients in your waiting room or in your community." [For more on this, see "Unhappy Postop: The Dark Side" below.]

Strategies for Success

Our surgeons offered the following suggestions for practices that are considering implanting these lenses:

• Don't make happy patients unhappy. Dr. Wallace notes that a staff member can unwittingly turn a happy patient into an unhappy one. "Some people refer to this as the '20/happy' concept," he explains. "A patient comes in; the staff member asks how he's doing, and he says he's doing great. Then the staff member measures his vision and finds that it's 20/30 or 20/40 uncorrected and says something like, "Oh, the first day postop you were seeing a little better than this.' All of a sudden the patient is not as happy, and it becomes a real issue.

"These patients need reassurance from the surgeon and staff that they're not in trouble," he continues. "At the same time, staff members—especially newer ones—may not realize that these lenses can really make a difference in a patient's quality of life, in spite of their downsides. Almost all studies are finding that patients who have multifocal lenses have a better quality of life than monofocal patients, but a lot of staff members have never seen those studies.

"It's important to have staff meetings to discuss what this is all about and how important a role the staff plays in patient satisfaction," he concludes. "You can emphasize that your goal is to make your patient care the best it can be, but if a patient is happy with his vision you don't want to undermine that. Experienced, more seasoned technicians may also be a good choice to discuss this with newer staff members, because they have a better understanding of the situations technicians find themselves in."

• Make the patient notice what he's gained. Robert T. Crotty, OD, who has been clinical director at Wallace Eye Surgery for 15 years, has had extensive experience examining and counseling presbyopic lens patients. He notes that a good way to minimize postop problems is to make patients aware of what they've gained. "Before surgery we have patients read a sheet of different-sized text without their glasses," he explains. "We ask them to circle the paragraph they can read and put their initials and the date next to it. After surgery we give them the same sheet and ask them to do the same thing so they can see how much they've gained. This is a direct confidence builder; it reinforces their progress, and if they're having problems, it helps them to see that the tradeoff was worthwhile."

• Update preop warnings as you learn from patients. Dr. Crotty notes that patient complaints after surgery may contain useful information in terms of what should be said to other patients preop. "Before surgery we give our patients a sheet describing what they can expect," he says. "We're always modifying that sheet. Whenever a patient raises a new issue, I tell the technician to add that to the sheet. Making sure patient preop expectations are accurate is an ongoing process."

• Don't use a formula to decide when to explant. "Sit down with these patients and ask how they're doing," says Dr. Mackool. "If a patient at two months says he can't drive at night, but it's not really a problem because his wife can handle that responsibility, then I'd give him more time. On the other hand, if he can't drive at night and that's a big problem, I'd change the lens. If you have a rigid view that two months isn't enough time to wait before explanting, the latter patient would be very unhappy indeed."

• Use NSAIDs postop. "As a rule, I put all my patients on a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory after cataract surgery," says Dr. Davis. "However, if a surgeon only uses NSAIDs on select patients, these patients should definitely receive them. NSAIDs are important as a means to prevent CME, and any postop issue that reduces contrast acuity, such as PCO or CME, will dramatically reduce the quality of vision with these lenses."

By and Large, a Happy Ending

Despite the significant pitfalls associated with the current presbyopic IOL options, most of the surgeons we spoke to agree that as long as patient selection is careful, the vast majority of patients end up satisfied. "Few of our patients are unhappy after both eyes have been done," says Dr. Wallace. "Most of the patients we see were selected because this was not likely to happen.

"I'm not going to claim that all of our multifocal patients end up never needing glasses," he continues. "But they understand the limitations of the lenses and they've decided they're doing the right thing. In fact, we might be misleading them by letting them think that explanting the lenses is a reasonable alternative, considering how successful we've been with other patients. They might miss out on a good long-term outcome."

Dr. Crotty agrees. "The key is handholding and reassurance—good communication with the patient," he says. "Over time, these patients will work out."