US

Pharm. 2006;6:34-38.

Each year in the United States, exposure to

excessive natural heat results in approximately 400 deaths, all of which are

considered preventable.1 In addition, about 200 Americans--most of

them 50 or older--die each year due to health problems caused by high heat and

humidity.2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

reported 3,829 deaths due to weather conditions between 1979 and 1999. Of the

3,764 deaths with a reported age, 142 occurred among children 4 years or

younger and 1,068 occurred among persons 75 years or older.3 During

that time frame, about 182 deaths per year were associated with exposure to

excessive heat due to weather conditions (annual deaths associated with

exposure to excessive heat ranged from 54 to 651 during these years).3

The body's inability to cope with heat,

i.e., the inadequate or inappropriate responses of heat-regulating mechanisms,

is often cited as the cause of such heat-related illnesses as heat exhaustion,

heatstroke, and dehydration. However, since deaths attributed to hypertension,

diabetes, and lung disease increase by 50% during heat waves, the risk of

heat-related death may depend more on the severity of the underlying disease

than on the severity of stress secondary to heat.4

Hyperthermia

An elderly person's body

temperature may rise when he or she is unable to rid the body of excess heat

or when the body produces too much heat, known as hyperthermia. When

air temperature rises above 98.6°F, the body gains excess heat and has

difficulty releasing it when concomitant high humidity makes evaporation of

sweat less effective.5 Seniors have more difficulty acclimating to

higher temperatures and humidity than do younger individuals. Even

temperatures in the low 90s can be very dangerous for older adults.2

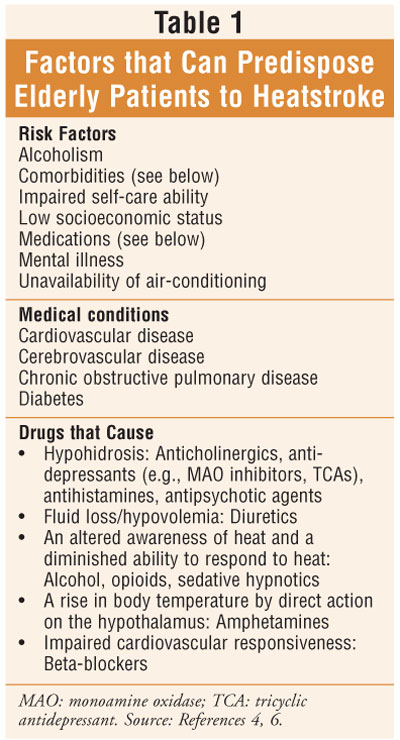

Additionally, certain medical conditions and medications may predispose

individuals to hyperthermia, complicating matters (table 1). Precautions

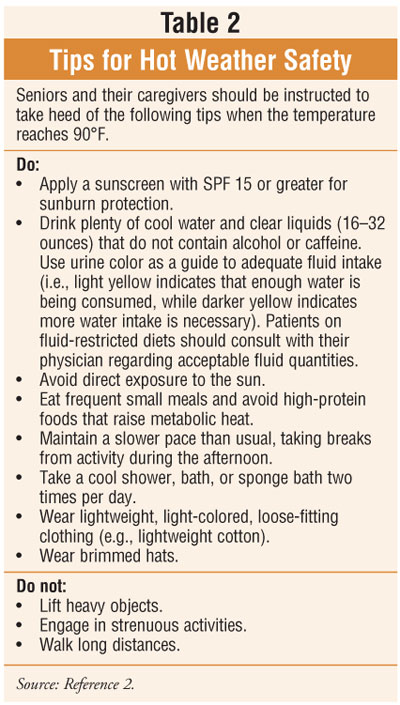

against hyperthermia include such commonsense recommendations as using

air-conditioning (e.g., in the home or at public venues), replacing fluids and

salts lost through sweating (drinking must continue even after thirst is

quenched), wearing light, loose-fitting clothing, avoiding strenuous exertion,

and misting or wetting the skin with cool water (table 2).5

Heat Exhaustion

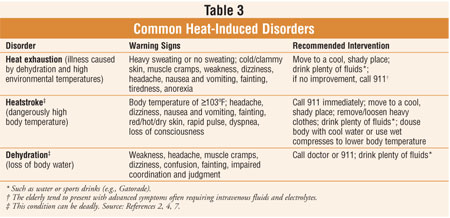

Heat exhaustion

is an illness caused by high environmental temperatures and dehydration (

table 3).2 The two major categories of heat exhaustion are water

depletion (producing hypertonic dehydration) and salt depletion

(loss of fluid and sodium chloride through sweating and replaced with

electrolyte-free water); the latter occurs in heat cramps.4

Treatment for seniors usually consists of intravenous replacement of fluids

and electrolytes based on abnormal laboratory values, since the elderly tend

to present late with advanced symptoms.4

Heatstroke

Heatstroke

is more common during summers with prolonged heat waves.6 During

hot, humid weather, heat exhaustion can progress to heatstroke if not treated.

Heatstroke occurs insidiously in the elderly, in whom the ability to dissipate

heat declines.4 In fact, people ages 65 or older are 12 to 13 times

more likely to experience heatstroke than are younger individuals.4

Heatstroke always involves a dangerously high body temperature (generally,

higher than 106°F or 41°C).5 While prodromal signs such

as dizziness, headache, and weakness may occur, loss of consciousness is

usually the first manifestation.4 Other symptoms and signs include

cardiovascular response (e.g., ECG changes); central nervous system

involvement (e.g., lethargy, stupor, coma); renal manifestations (e.g., renal

failure secondary to rhabdomyolysis); severe hypokalemia (thought to be

secondary to increased aldosterone secretion); elevated liver transaminases

(jaundice is common while hepatic damage is rare); and coagulation defects

(e.g., elevated prothrombin and partial thromboplastin; decreased fibrinogen

level).4

While many use the term heatstroke loosely,

the condition constitutes a medical emergency and requires hospitalization and

continuous monitoring.4 Risk factors, including use of certain

drugs and some medical conditions, may predispose a patient to heatstroke. It

is prudent, therefore, to obtain a thorough medical and medication history to

help prevent heatstroke or elucidate its cause.4 Increased public

awareness and prompt intervention by family members, caregivers, onlookers,

and health care professionals can reduce morbidity and mortality from

heatstroke.4

Dehydration

Dehydration is the most common

fluid and electrolyte disturbance in the elderly; hot weather is a common

contributing factor.4 A popular misconception is that a dehydrated

person experiences intense thirst. Thirst is an unreliable indicator of

dehydration because rapid fluid loss overwhelms the body's normal thirst

mechanism.7 Common symptoms include diminished coordination,

fatigue, orthostatic hypotension, and impaired judgment.

Diarrhea is a major cause of morbidity and

mortality in seniors because of a decreased capability to replenish fluid

losses and to tolerate intravascular hypovolemia associated with dehydration.

4 Seniors may be more susceptible to infectious diarrhea due to a higher

incidence of decreased mucosal immune function, luminal stasis (e.g., from

motility disorders or previous surgeries), or hypochlorhydria and achlorhydria

(e.g., from gastric acid–suppressing medications or pernicious anemia) in the

elderly.4

According to the CDC, traveler's diarrhea

(TD) is characterized by the fairly abrupt onset of loose, watery, or

semiformed stools associated with abdominal cramps and rectal urgency.8

Symptoms may be preceded by a prodrome of gaseous and abdominal cramping, and

additional symptoms such as nausea, bloating, and fever may be associated.

8 Vomiting may occur in up to 15% of those affected.8

Symptoms are generally self-limiting and occur abruptly during or soon after

an individual returns from travel. Attack rates are commonly reported to be

between 20% and 50%.8

The primary causes of TD are infectious

agents, which include enteric bacterial pathogens, viral enteric pathogens,

and parasitic enteric pathogens. Twenty percent to 50% of TD cases are

attributed to unidentified causes. TD risk is associated with the

categorization of the travel destination: high-risk, intermediate-risk, and

low-risk (see CDC Web site below).8

Prevention methods include strict attention

to food and beverage ingestion (e.g., drink bottled beverages and avoid

consuming products sold by street food vendors) and the use of

nonantimicrobial medications and prophylactic antimicrobial agents. The CDC

reports that adherence to restrictive food and beverage measures is difficult

for travelers, that antiperistaltic agents (e.g., diphenoxylate, loperamide)

are not effective in preventing TD, and that prophylactic antibiotics have no

effect on viral and parasitic diseases and may render a false confidence about

consuming risky food and beverages.8 Therefore, the CDC does not

recommend prophylactic antimicrobial agents for travelers, but rather,

sensible dietary practices as a prophylactic measure, since available early

treatment renders excellent results. In special circumstances, prophylactic

antimicrobial therapy along with a risk-benefit analysis is advocated for

travel.8 For the most recent recommendations for the treatment of

TD, see the CDC Web site at: www.cdc.gov/travel/diseases.htm#diarrhea.

Protection from Sun Exposure

Protection from excessive sun

exposure that might contribute to sunburn, medication-related photosensitivity

reactions, skin cancer, and heat-related illness is an important issue to

address with seniors. Sunscreens with a high sun protection factor (SPF) of 15

or greater should be applied to all exposed areas of the skin when outdoors,

and the use of long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and wide-brimmed hats is also

recommended.5

Information List for Safety

Another safety tip is for seniors

to always have a patient information list with them, especially when traveling.

9 The list should include, but not be limited to, name, address, and

allergies of the individual; emergency contact information; list of

medications (generic names included) and conditions for which they are being

utilized; and name, address, and telephone and fax numbers of primary

physician and pharmacy. It is also wise for seniors to consider wearing a

medical identification bracelet, if applicable.

Conclusion

Heat-related illness is a major

cause of preventable morbidity. During the summer, sustained exposure to high

temperatures puts the elderly at particular risk of suffering from conditions,

such as heat exhaustion or heatstroke, stemming from dehydration. Increased

public awareness of heatstroke and prompt intervention by family members,

caregivers, and health care professionals can reduce morbidity and mortality

of heat-related illnesses. Health care practitioners should advocate

familiarization with risk factors and preventive measures to patients, their

families, and caregivers.

REFERENCES

1. Semenza JC, Rubin CH, Falter

KH, et al. Heat-related deaths during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. N

Engl J Med. 1996;335:84-90.

2. The American Geriatrics Society

Foundation for Health in Aging. The American Geriatrics Society's Hot Weather

Safety Tips for Older Adults. Available at:

www.healthinaging.org/public_education/hot_weather_tips.php. Accessed April 5,

2006.

3. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Heat-Related Deaths--Four

States, July-August 2001, and United States, 1979-1999. Available at:

www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5126a2.htm. Accessed May 1, 2006.

4. Beers MH, Berkow R, eds. The

Merck Manual of Geriatrics. 3rd ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co;

2000:562-563, 659-663, 923-930, 1085-1092.

5. Beers MH, Jones TV, Berkwits M, et

al., eds. The Merck Manual of Health & Aging. Whitehouse Station,

NJ: Merck Research Laboratories; 2004:

31-32, 385, 889.

6. Helman RS, Habal R. Heatstroke.

eMedicine from WebMD. Available at: www.emedicine.com/MED/topic956.htm.

Accessed May 1, 2006.

7. Dehydration and heat-related

illness. US Pharmacist. 2000;25:82.

8. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Traveler's Diarrhea. Available at:

www2.ncid.cdc.gov/travel/yb/utils/ybGet.asp?section=dis&obj=travelers_diarrhea.htm&cssNav=browseoyb.

Accessed May 10, 2006.

9. Zagaria ME. Tips for traveling

seniors. US Pharmacist. 2005;30:32-36.

To comment on this article,

contact

[email protected].