By Preston Fassel

“Have you got it?”

Wesley Robinson, 17, great big bulldog of a boy, leans over the counter at Steve’s Sundry, burly elbows jamming into the little wire racks of pocket books and digest magazines, wiping his forehead with a wadded white bandana from his jacket pocket to provide the clerk the courtesy of not dripping sweat all over the place. Though fall has come late to Oklahoma this year, it is always too hot for someone of Wesley’s stature and hirsuteness, a discomfort compounded by his insistence on a sports coat, tie and hat; Wesley makes the sartorial misstep of many big men, believing that adorning himself in something elegant and two sizes too large will mask his bulk rather than draw attention to it.

“I’ve got it; you know I’ve got it.” Jack, smaller than Wesley, sleek from head to toe, silver hair slicked back, rayon shirt pressed crisp, smiling crookedly at Wesley, half indulgence, half contempt, had agreed to put the order in for the boy a week ago, fielding his inquiries ever since. Every third phone call he’s answered in the interim, “Is it in, have you got it yet,” Jack being used to persistence but not this kind of persistence; Steve’s after all specializes in this sort of business, special orders, special books, special records, what’s too obscure or too subversive or too unobtainable for mainstream proprietors in Tulsa to be bothered with, what’s too fantastic or foreign for the kids from Ayastigi—20 miles west, a thousand worlds away—to live without.

The clerk digs beneath the counter, manila envelopes wrapped in rubber bands, orders for the other kids eager to experience life outside of Oklahoma secondhand, finds the one marked ROBINSON in fat black magic marker. “I know this is gonna make your aunt happy. No one tying up her phone line anymore.”

“Uh-huh,” replies Wesley not hearing, usually one to partake in small talk, banter, the niceties of social interaction with the service industry, one of the few situations in which he feels completely at ease, today more eager to review his prize, his tool, his long-awaited acquisition, a stepping stone toward something greater. The pieces are falling into place; just a few more errands and everything will be ready, and he and Saffron will be celebrating Thanksgiving 1976 in New York City.

Wesley puts his money on the counter, neglects to collect the 25 cents in change he’s owed; tip to Jack; knows he’s annoyed the heck out of the poor guy. Jack watches him go through the big glass panes of the front of the store, Wesley hurrying out to his aunt’s masticated pickup to jack up the air conditioner and tear open the package, pull out the magazine inside, can’t fathom what fascination the subject matter holds for the boy.

He’s never seen anyone so interested in glasses.

* * *

Can I smoke in here?”

Saffron Dultworm, 18, pale, lots of beads and denim, stares at the woman behind the reception desk, walleyed and vacant, and lost in contemplation of some far off and unseen object. “Excuse me? Can I smoke in here?” And there being no response she fumbles in her bag for her pack, shakes out a smoke, and is in the process of flicking her lighter when the woman’s head swivels toward her and—

“Hey. You can’t smoke in here.”

Saffron freezes, thumb and index finger in mid-movement, turns her eyes up toward the receptionist.

“Why not?”

“It’ll gunk up the equipment.”

Somewhere in the back of the office, behind what appears to be a row of cubicles, the sound of grinding gears and then a high-pitched, mechanical whine, like an ancient buzz saw pressed into service under dire and possibly torturous circumstances. Saffron regards the noise, regards the layer of dirt caking her chair, the dust mites dancing cylindrically in the single shaft of golden light managing to penetrate the smoked-over windows, makes to say something but stops herself, stuffs the cigarette back into her purse. Decides to amuse herself with the lighter instead. The receptionist goes back to studying whatever lay a thousand yards away.

Saffron smiles. Not smiles, but smirks, a smirk being a rare enough sight on her long, drawn face, a smile even rarer, a genuine one nigh impossible. Gone: Soon, all of this will be gone. A faded nightmare; a forgotten trauma; in a few days, Ayastigi will be those things and nothing more.

Saffron Dultworm is running away from home.

Kids run away from Ayastigi all the time, not every week or every month but at least a handful every semester; really it’s the kind of town that was pretty much invented as a place for kids to run away from, with its one strip mall and two grocery stores, eight churches, one drugstore, zero record stores, 20,000 people, a drive-through tobacco stand on the side of Elm that’s a sort of hangout if you’re that desperate, that bored, that type of person. Mostly, the kids run away to Tulsa, where the majority has been spending their weekends anyway; a smaller number make it to Joplin or Branson, and those braver still head onward to St. Louis. Postcards from Ayastigi’s desperate youth have drifted back home from as far as Aspen and San Francisco; Bret Miles wrote his little brother from Miami.

Saffron Dultworm will be running away to New York.

First, there’s one last order of business to conduct.

She wants a new pair of glasses.

Wants: the operative word. The pair she’s got now works relatively well, the prescription only a year and a half old, the frames somewhat more so, selected by her father from amongst the clearance merchandise over a decade ago, rimless oval glasses culled from the bottom of a wooden drawer in the heyday of 1964’s plastics craze. Dr. Horner, since deceased, explained to Drayton Dultworm that perhaps rimless glasses were not the optimal choice in frames for a 6-year-old girl, bourbon-breathed Drayton retorted that he’d buy his little girl anything else that Doc Horner could suggest, as long as they were cheaper, and while he was at it, could he go do certain things to himself? Those same frames, lensed and re-lensed in the ensuing years, the baby fat melting away and the crop-top growing longer and more viney, Saffron Dultworm transformed from a plump little child into a tall, wan girl and those glasses did nothing for her. Those same frames: the last husk of this life to be shed before the great migration North; her first decision as an independent woman of the new age.

Outside, the sound of a belabored truck engine, tires kicking up loose parking lot gravel, and Saffron turns away from the dust show, squints against the light, sees Wesley pull up, her partner in crime, the beginnings of a genuine smile capped before anyone sees. Wesley Robinson—her boyfriend. Still not used to that word, “boyfriend,” what other girls have, have had since they were 13 or 14, when Saffron was holed up in her room with too many books and too many records and too few people; boyfriend, can’t adjust to it, has used the word aloud approximately once. Introducing Wesley to her father, Wesley nervous and twitchy and standing too erect with his hands folded behind his back and Drayton eyeing him suspiciously before leaning into Saffron to whisper, “Where’re his arms?”

Times like that she wished she could get a word of advice from mom.

Wesley comes in, and Saffron stands and they meet in front of the door, Wesley still not entirely secure in what to do with his arms, his lips, and while he knows that this would take points from his favor with most other girls, there is some charm in this naivety for Saffron, that smirk twitching again, lonely gray eyes staring into Wesley’s, content that, at least for as long as he’ll have her, this will be the face she’ll be seeing every morning.

“Sorry I’m late,” Wesley says. Saffron can’t help but bristle a bit, knows what is coming next. “The truck was giving me problems, and then I hit every red light, and I had to make a stop before coming here, and then...”

“You don’t always have to apologize so much. Geez, you were 10 minutes late.”

“I didn’t want you to worry.”

“Ten minutes. I know you can take care of yourself.”

“Still.”

“Wesley...”

And at once the two become aware of something amiss, turn to see the receptionist has turned her thousand-yard stare in their direction.

“Take a picture,” Saffron says, and the receptionist lets out a somewhat dejected sigh and swivels her head back around.

“Anyway,” Saffron says.

“They can do this in an hour, really?” Wesley asks. He regards the dispensary with a combination of skepticism and awe. His own hyperopia is corrected with a pair of tinted aviators purchased on the other side of Ayastigi from his Aunt Meg’s optometrist, a process requiring a good week’s lead time.

“I know, right?” Saffron says. “But anyway, come here and look...”

“Hold on. I’ve got something to show you.” Wesley giddy now, Saffron a bit nervous; Wesley’s surprises are often ineffective, not for his own lack of trying but overeager ineptitude. Copies of books she’d already read (and hated); records she’d already listened to (and hated); the eight-track player he bought her for her birthday, to be used in a car already outfitted for cassettes. Before Saffron can respond, Wesley has presented her with the magazine, his prize, rolled into a tight cylinder from having been stuffed in his jacket pocket.

“Uh, what’s this?”

“It’s a magazine.”

“I can see that.”

“About glasses.”

“Um... ok.”

“Dr. Hudges had a copy at his office the last time I went. I had the guy at Steve’s order me in a copy. All the way from New York! Here, look.” Wesley, opening the pages, flipping too quickly for Saffron to make good sense of what she’s seeing. “They show you what’s new, what’s trendy, it’s almost like the Sears catalog but it’s all about eyeglass frames and who’s wearing what now.”

“Bubbe, I don’t need a magazine to help me pick out clothes. I’ve been dressing myself since I was 15 and dad stopped paying attention to where he left his checkbook. Look, come here.” Saffron leads Wesley through the small dispensary, the heavy orange shag beneath their feet clashing harshly with the muted seafoam green of the walls, the stark white of the frame cases. Saffron has already laid out a line of frames on a Formica countertop in the back center of the dispensary, a line of CatEye glasses in a variety of colors, sizes and degrees of severity.

“I narrowed it down to these before you got here. I just want a second opinion, which ones you like the best.”

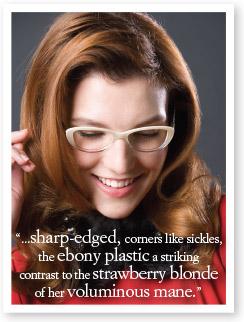

Wesley frowns, begins to say something, as Saffron puts on the first pair of frames, sharp-edged, corners like sickles, the ebony plastic a striking contrast to the strawberry blonde of her voluminous mane. “Too much?”

“A little...”

The next pair, sleeker, dark at the top and fading into translucent white, the edges softer, more modish, a severe look with her skin tone but a comfortable fit on the bridge of her aquiline nose. “How about these?”

“They’re… nicer.”

“You’re not giving me very good feedback.” Door number three: deep plum, filigree at the corners.

“Saffron... These are old women glasses.”

“Says who?”

“Anyone! Everyone! Look in here!” Back to the magazine. “None of the girls in here are wearing CatEyes. Only old women who play the organ at church and hang out at bowling alleys wear CatEyes. You should look young. Come here.”

And in spite of herself, Saffron is standing before a case of metal frames, steel and monel, and aluminum glistening beneath fluorescent spotlights, great rectangles and trapezoids and octagons, narrow bridges, thick temples, a cornucopia of metallic excess. “This is what women in New York will be wearing,” Wesley says. “They’re almost as light as rimless glasses, but sturdier. And they aren’t so dark as plastic frames so they don’t overwhelm your face.” Wesley stands back, ponders Saffron’s face a moment, assessing it now not as something he wants to kiss but in degrees of size, shape, the way he would study a portrait, a movie scene. Then, returning to the display case, he retrieves a pair of frames, feminine in the elegance of their curves, masculine in their sheer scope. He moves to put them on Saffron.

“Hey. Don’t do that.”

“Well, you put them on then.”

“I don’t want to put them on.”

“Just so I can see what you look like?”

Saffron puts them on, finds herself standing beside Wesley in front of a dust-caked display mirror.

“It’s a new look for you,” Wesley says. “A... good look. They don’t draw your face out the way the rimless did. They sorta break up your features.”

“I don’t need anything broken up.”

“I didn’t mean it in a bad way.”

“I know.”

“Saffron... Do you remember when they took my picture for the school newspaper?”

“When you won the science fair, yeah.”

“Remember what you told me?”

Saffron thinks for a moment. “That you should have worn something other than khaki pants if you insisted on that garish yellow jacket.”

“Exactly. And then?”

“I don’t remember.”

“That someone as handsome as me should always look his best.”

“Huh. Yeah, I did.”

“So.”

“So?”

“So... Someone so...” And Wesley fumbles for a moment, compliments still awkward on his tongue. “You... you should always look your best. Because... I love you, and... I think you’re… lovely… and… You should always look your best.”

A pause. That empty space in their conversations where Saffron finds herself unsure of how to respond to kindness. “Oh… That’ very sweet, Wesley.”

“And I think these make you look your best.” Wesley smiles. A hand in her hair. The couple stare at themselves in the mirror; the couple stares back. A pair of quizzical kids studying themselves through soon to be adult eyes, wanting so badly to look the part.

Saffron smirks. “Really? You do?”

“...Wonderful.”

“All right then. These are the ones. These are the glasses I’ll wear to New York.”

“Great! Are you sure you don’t want to try any other shapes on? Just to get an idea?”

“I trust your judgment.”

“Cool... Hey, this didn’t take as long as I thought. Even though I was late, we can still catch a show at Circle Cinema.”

“What’re they showing?”

“Carrie. I know you’ve already seen it but...”

“I’d love to. Hey, just out of curiosity, if I had to get one of the frames I’d picked out, which looked the best?”

“The old women glasses?”

“…Yes, Wesley. The old women glasses.”

Wesley thinks a moment. “The faded ones, I guess. They’re sort of hippie-like, so they go best with the rest of your look.”

“Just wondering,” Saffron says. She fumbles in her purse, comes out with her father’s checkbook. “Hey,” she calls to the receptionist. “Who do I make this out to?”

* * *

They make it to the Circle in time to catch the last preview before Carrie. They take up their usual spot in the theater, back row, to the right. Being young, in love and slightly to the left of reckless, they only spend half their time in the theater watching the movie. Afterwards, the dispensary. Saffron sits at a dispensing table, Wesley beside her. The high-pitched whine in the back ceases, signaling the appearance moments later of a small, balding man in a lab coat, carrying a black jewelry tray. He places the tray before her; Saffron’s new glasses peer up at her. She removes her current pair, puts the new ones on. Looks at herself in the little tabletop mirror.

“What do you think?” the man asks.

“That I’m ready to go to New York,” Saffron says.

* * *

Dusk in Ayastigi comes slowly, the slouched skyline and grasslands giving an ample view of the vermillion sunset that comes daily in the autumn to bask the whole of the city in a soothing glow that makes the young and restless believe, if only for its duration, that this isn’t such a bad place to come of age. The last rays of light are fading, the horizon turning over to royal blue when Saffron Dultworm knocks on the dispensary window; the receptionist is just about to switch out the light. Saffron holds up her father’s checkbook.

“You still have those other glasses? What did he call them? The fades?”

* * *

The Dultworm house is almost completely unlit when Saffron returns home, the only illumination in the house coming from the floor television in the living room. Locking the door behind her, Saffron doesn’t bother to pause, knowing what she’ll see. Almost to the stairs, a voice, nasal and slurred, calls out to her.

“Virginia? ’Ginia, that you?”

Saffron steps back. Seated in his recliner, shirt undone, tie slung around his shoulders, Drayton Dultworm cradles a bottle in his lap, staring vacantly at the set.

“Saffron. I told you, my name is Saffron now.”

“If that ain’t the stupidest name ever. I named you. ’Ginia. Virginia.”

“I know you did.”

“Where you been?”

“Out with Wesley.”

Drayton shakes his head. His eyes never leave the set. “Don’t know what your momma’d say about dating a boy don’t got any arms. Ain’t no future in that.”

Saffron sighs and climbs the stairs to her bedroom. Safely locked away, she removes her new metal glasses, places them on her bed. Retrieves the case containing the CatEyes from her purse, puts them on. Studies herself in her vanity mirror. Casually, she picks up the metal frames, cradling them between her hands. She squeezes each lens between her thumb and index finger. Begins to bend her wrists backwards. The bridge bends and twists into a metallic pretzel.

“Oops,” she says.

* * *

Gone. Soon, all of this will be gone.

Midnight in Ayastigi, a week later. Somewhere in the Dultworm house, Drayton snores and coughs from wherever he passed out. When he wakes in the morning he’ll find no daughter, no note. In the driveway, Wesley waits patiently behind the wheel of his aunt’s truck, even the idling of the engine unable to wake Drayton from his slumber. In her bedroom, Saffron Dultworm finishes packing. One bag: the agreed upon luggage to be toted along to New York, to preserve room in the bed for sleeping en route and reduce weight to enhance fuel efficiency.

Saffron Dultworm leaves a great deal behind the night that Wesley Robinson takes her away from her old life. She leaves behind her records, her books, the great majority of her clothes, hats she liked and jewelry she once wore with pride, stuffed animals that once gave her comfort and knick-knacks that made her room look more a home to her than the rest of the cursed house. Something she does not leave behind, tucked safely away at the bottom of her bag, nestled securely between lays of T-shirts and blue jeans: a single, framed photo, black and white already beginning to fade into gray with age. Drayton Dultworm, sober, clean shaven, stares sternly but proudly into the camera. Beside him, Ingrid Dultworm cradles their newborn daughter, Virginia’s bald pate betraying nothing of the hair it will one day display. The expression on Ingrid’s face is beatific; she shows no symptoms of the lingering infection that would take her life just days after the photo was taken. The look in her eyes is one of peace, one of goodwill and prayers and hopes for her daughter, her eyes gazing into the future that lay beyond the camera, beyond the abyss into which she will soon be traveling, eyes shining bright with life through the lenses of her thick CatEye glasses. ■