SPECIALTY FITTING PATIENTS WITH DIFFERENCES, MASTOID AND NOSE

By Preston Fassel, BS

Release Date: June 1, 2017

Expiration Date: January 27, 2019

Learning Objectives:

- Understand the presence and purpose of the mastoid process and how to properly compensate for it when adjusting glasses.

- Understand the special needs of a patient with Down syndrome and appropriate frame adjustments and choices for Down syndrome patients.

- Be able to comfortably adjust a pair of frames for a patient who has had his or her nose broken.

Credit Statement:

This course is approved for one (1) hour of CE credit by the American Board of Opticianry (ABO). General Knowledge Course SWJHI001

Faculty/Editorial Board:

Preston Fassel, is an optician in the Houston area. His interests are in the history of eyewear and all things vintage. He writes for The Opticians Handbook and 20/20 Magazine and has also been featured in Rue Morgue magazine, where he is a recurrent reviewer of horror and science fiction DVDs.

In recent years, some of the old lessons and knowledge of professionally fitting eyewear have slowly been lost for a variety of reasons, from frames only being offered in one size to the difficulty of on-the-job-training. In fact, the number of opticians who learn the trade solely through “on-the-job” increases the odds that new opticians are being trained entirely by people who, like themselves, had little to no formal optical training.

As more and more old-schoolers leave the profession, the tips, tricks and knowledge they possessed are slowly leaving the field, saddling any truly dedicated modern optician with the task of handling unique and difficult situations without the wisdom of their predecessors. After all, there are some situations that are best addressed by years of experience; still others may seem daunting when they are, in reality, simply part of routine adjustment and dispensing.

Rudyard Kipling famously laid out his criteria for manhood; whatever those similar qualifiers for opticianry may be, I’m going to go ahead and add three more to the list: compensate for the mastoid process; dispense for a patient with Down syndrome; and adjust for a patient who has had his or her nose broken (repeatedly).

THE RARE WOOLY MASTOID

“These glasses are giving me a headache.” Along with “It’s going to cost HOW much?” and “You’re the greatest human being I’ve ever known,” it’s probably one of the most common phrases every optician hears. We hear it so often, in fact, that most of us probably go into autopilot when a patient says it to us. “Please have a seat,” we respond, and while our eyes are assessing the nosepads and endpieces and the patient’s facial anatomy, our minds are on dinner tonight or what we’re going to see at the show this weekend. Before we know it, the glasses are back on the patient’s face and he or she is hopefully smiling and considering a second pair of sunglasses. Yet, there are always those situations, which deviate from the norm. What happens when the patient isn’t smiling when all is said and done? What happens when he or she comes back hours or days later, complaining that their headache is still present—or has gotten worse? You noodled the nosepads; you tweaked the temples; you propped the panto. Suddenly, that dreamy autopilot state is fading, and you’re brought to a cold, hard reality: An adjustment issue with which you’re not familiar. You rule out an Rx issue; the patient is still frustrated and in discomfort; what do you do? What did you miss? Where have you gone wrong?

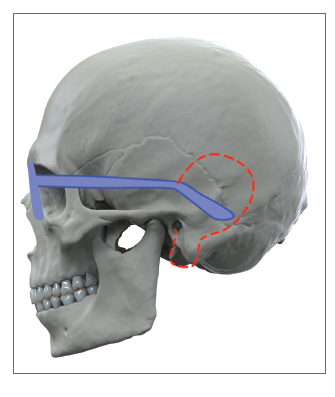

Put your fingers just above your ears. Now, slowly move them back and down, following the natural slope of your ear. You should eventually feel a pair of fairly symmetrical bumps toward the rear of your skull, about where it starts to curve around toward the back of your head. This is the mastoid process.

The mastoid process is a part of the mastoid bone, part of the temporal lobe. Its function is twofold: 1. It’s filled with air cells that connect to and help drain the middle ear, and 2. It acts as an attachment point for a variety of muscles, including the digastric, splenius, capitis and sternocleidomastoid. It’s this second reason that you’ll find the mastoid process is larger in men than in women: Men’s larger muscles require a larger, sturdier attachment point. Now, the question of course is: Why does any of this matter? Our focus is on the eyes, after all, and secondary to that, the parts of the head that affect wearing eyeglasses. As it turns out, this strange little lump has a far greater impact on frame adjustment than you’d ever guess.

In addition to being the anchor site of many muscles, the mastoid process is sort of at ground zero for a variety of sensitive nerves, as well. Here, you’ll find the lesser occipital nerve, the greater auricular nerve and the lesser auricular nerve. Being in such close grouping to one another, it makes this region of the head something of a minefield for sensation—and here’s where the picture is probably starting to form why this is so important for us. By introducing a foreign element into the area—such as, say, an eyeglass temple—we’re creating the possibility of undue pressure being placed on one—or worse, all of the nerves. That’s a recipe for disaster—or for example, a painful headache. This is why when fitting and adjusting frames, it’s imperative to compensate for the mastoid.

Once upon a time, it wasn’t unheard of for a routine dispense to involve the optician running his or her hands along the sides of the patient’s head and behind his or her ears. Among a variety of other factors, part of this allowed to check that temples weren’t contacting the mastoid in an uncomfortable manner. While running your hands along your patient’s head may not be the best idea in today’s world (at least not without asking first—especially with minors!), it doesn’t reduce the need to ensure that your patient won’t be coming back later with a splitting headache… and giving you one too.

The first thing to do is get a clear view of the mastoid area as it relates to your patient’s glasses. With his or her glasses on, ask your patient to either bend his or her ears forward to provide an unobstructed view, or ask for permission to gently bend the patient’s ear back yourself. If your patient has longer hair, you may also need him or her to put it back or up to provide the clearest view. Now, take a look at where the temple tip touches the skull. Depending on the topography of your patient’s head, you’ll want the tip to do a variety of things: It should either be in front of or behind the mastoid; and it may need to be slightly contoured.

The first thing to do is get a clear view of the mastoid area as it relates to your patient’s glasses. With his or her glasses on, ask your patient to either bend his or her ears forward to provide an unobstructed view, or ask for permission to gently bend the patient’s ear back yourself. If your patient has longer hair, you may also need him or her to put it back or up to provide the clearest view. Now, take a look at where the temple tip touches the skull. Depending on the topography of your patient’s head, you’ll want the tip to do a variety of things: It should either be in front of or behind the mastoid; and it may need to be slightly contoured.

Remember that you want the bend of the temple tip to curve smoothly behind the ear, downward at about 45 degrees with the bend at the crest of the top of the ear where it attaches to the head. Too sharp a bend, and they’ll be too tight on the patient, dig into the back of the ear and ride up on the ear, causing another sort of headache; too loose of a bend and you’ll avoid the mastoid but you’ll also have a patient with slippery glasses. This is where you may run into some difficulty with finding the right place to angle the temple. Depending on the size and placement of the patient’s mastoid, you may need to curve the temple outward to avoid striking out while at the same time keeping the tip secure against the back of the patient’s ear. Ideally, you’ll be able to get the temple relatively flush with the individual’s head without striking the mastoid, but especially with those patients with a larger mastoid (more often than not this will be males, but I’ve also encountered some women with larger, very sensitive mastoid processes), this may be an issue. Be sure to work in slow, steady increments when curving the temple so that it bends just enough to avoid striking the mastoid without sticking out. You want it sloped, not bowed. Done properly, the patient’s temples won’t contact the mastoid at all; the glasses will be secure, snug and comfortable; and you can go back to daydreaming about what kind of junk food you’re going to smuggle into the theater this Saturday.

SPECIAL NEEDS FOR SPECIAL NEEDS

Every patient’s needs are different, just as every patient’s facial structure is different, and every patient’s level of comfort with his or her glasses varies. This is especially true for patients with Down syndrome.

Down syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by a partial or full copy of the 21st chromosome. It results in delayed growth and the formation of particular facial characteristics. Down syndrome is not as rare as once believed by the general population, occurring in roughly 1 out of every 1,000 births. This is particularly important for opticians: 40 to 90 percent of all people with Down syndrome suffer from some sort of refractive or accommodation error. Additionally, out of this portion of the Down syndrome population, 70 percent have unique structural characteristics of the face and skull that require unique adjustments to frames that would not benefit any other patients, and indeed, they may even require their own special frames.

First, let’s look at the unique facial characteristics of someone with Down syndrome. A quick disclaimer: Of course, every individual is unique, both in his or her personality and appearance. Not every patient with Down syndrome will have the exact same facial structure or face the same challenges; this is simply meant to be a guideline for dispensing to patients with Down syndrome based on averages encountered in the population.

On average, a patient with Down syndrome will have a narrower head than nonDown syndrome patients in the same age/ sex/ethnic group. They will also tend to have extremely flat to almost no bridge, and the nose also tends to sit lower than average. Down syndrome patients also tend to have a shorter distance between the front of the face and the back of the ears. The round face shape is more common in Down syndrome patients than in a similar cohort among non-Down syndrome patients, with wider jaws and a shorter distance between eyes, nose and mouth. As you can imagine, each of these characteristics on their own would present a unique challenge; taken together, they represent an entire series of difficulties faced by Down syndrome patients in getting properly designed and adjusted glasses, as well as difficulties faced by opticians in properly dispensing and adjusting frames for patients with Down syndrome.

The biggest difficulty is faced by children with Down syndrome. As patients age, some options open up in terms of adjusting and modifying teens and children’s frames to fit comfortably. Temples can be shortened on wire frames, and adjustments made to nosepads to compensate for the flatter nose bridge. However, even the smallest of children’s frames will probably prove too large for a child with Down syndrome. Attempting to rig up or modify a frame in these circumstances will almost certainly be disastrous. For one, metal frames may not be suited to every child, especially very young children who will be prone to breaking the nosepieces. For another, as many patients will require a bifocal for accommodation issues, even the most judiciously modified frame may not place the patient’s eye in a desirable position due to the placement of nosepads on a very low, flat bridge. The best solution then becomes special frames for special patients.

In recent years, manufacturers have stepped forward to begin providing frames especially for Down syndrome patients that are both functional and cosmetically appealing. For a well-known and versatile frame, consider Specs4Us, frames designed by the mother of a child with Down syndrome. Specs4Us frames are sort of upsidedown Ful-Vues: The temples and bridge are mounted three-quarters of the way down the frame, so that the bridge places the lenses higher to be at better eye height. This allows not just for comfortable vision for the patient but also aids an optician in the event that he or she requires a multifocal. Additionally, the temples are shorter, and the distance between the temples are appropriate for the width of the average Down syndrome child’s head. The frames are flexible and easily adjusted, which is also a sort of an Achilles heel: for the particularly rambunctious child, they also easily come out of adjustment, which may require frequent trips to the optician on the parents’ behalf until their little one gets used to wearing his or her glasses.

Most opticians are probably aware of Miraflex frames. Miraflex frames are durable, flexible hypoallergenic plastic frames meant to withstand the rigors of being worn and handled by a child. The frames come in a variety of eye shapes and sizes to accommodate different patient prescriptions and faces, and can be ordered in a variety of colors. They attach to the child’s head by way of a soft, comfortable elastic strap that holds them securely in place, making them ideal not just for children in general but Down syndrome children especially, as there’s no need to adjust temples or properly situate nosepads. Keep in mind, though, that Miraflex frames may have a limited shelf life in terms of viability. Children with Down syndrome can be and are just aware of their own appearance as any other children, and once they pass a certain age, their glasses may become a source of social stigma. Many young children in preschool, kindergarten and elementary school will wear Miraflex frames; however, as they enter the older grades of elementary school and pass into middle school, the patient and other children will almost certainly begin to associate his or her frames with “babies,” potentially resulting in poor selfesteem on the child’s part and bullying on the art of insensitive classmates.

A compromise between Miraflex and Specs4us are Tomato Glasses. Like Miraflex, the frames are a soft, flexible plastic for durability; although many of the designs are similar to Miraflex’s, there are also a variety of frames that look very similar to the currently popular retro-inspired zyls that have been dominating the market. The temples and width, like Specs4Us, are crafted to fit the size of the average Down patient’s head. A unique feature of Tomato frames are their versatile nosepads: Rather than saddle bridges, Tomatoes have attached adjustable nosepads, which can be mounted at three different points on the back of the bridge to best compensate for the patient’s natural nose position. For child patients just getting used to the glasses, there’s an optional strap that parents can attach to the back of the glasses to keep them in place. The temples are also a soft, pliable plastic that can be easily adjusted and which provide comfortable cushioning on the back of the patient’s ear.

Of course, for older patients, it’s also possible to modify metal frames, adjusting the nosepads to lift the frames up higher on the patient’s face and shortening the temples (though of course this only works with thin, uniformly narrow temples). Some opticians might also have success with adjusting some of the new “universal fit” zyl frames recently marketed to the African-American and Asian communities, as these frames are specially designed for patients with flatter bridges. The most important consideration is making sure your patient will be comfortable, have the highest level of vision possible, and be happy with the way he or she looks. Being aware of the issues faced by Down syndrome patients is half the battle in and of itself; after that, it’s simply a matter of knowing the options, discussing them with your patient and/or their parents, and coming to an informed, viable solution.

THE BROKEN NOSE BLUES

For the final part of this CE, we’re venturing into much surlier territory: broken noses— more specifically, repeatedly broken noses. Unless you work near an ER trauma ward or a particularly raucous honky-tonk, odds are this is going to be the least common uncommon issue of them all. However, broken noses aren’t unheard of, and if one crosses your path in two pieces or five, it’ll be helpful to know how to work on them.

In fitting a patient for a broken nose, sensitivity is the name of the game. Similar to our work with the mastoid process, you’ll want to work to avoid putting pressure on the parts of the nose which have been broken, adjusting the bridge in such a way as to evenly and comfortably distribute pressure on those parts of the nose best suited for it. Frame selection here will result from a number of factors. The best option would be a titanium frame, or better still, titanium rimless to minimize the weight being exerted on the patient’s nose. Plastics are essentially out of the equation, unless you’re dealing with a very lightweight material such as Optyl or certain types of nylon, and you’re willing (and able) to install adjustable nosepads on the frame.

Removing your patient’s fashion preferences from the equation though, the best route to go is a frame with some sort of fine metal saddle bridge, one which allows you to shape the frame to the crest of the patient’s nose and minimize contact with the broken portions. Of course, unless your patient is a vintage aficionado (or you truck in “deadstock” frames yourself), choices for metal saddlebridge frames are scarce (though some frame lines, including Europa’s Scott Harris Vintage and Saville Row do offer them). Your best bet then, is a totally rimless frame with a modified wire bridge. This is a task that will take a great degree of skill, experience and professional aptitude; it’s not an exercise for the newbie or the faint of heart, but successfully completing it won’t just leave you with a happy patient, but leave you feeling like an optical master.

In order to modify the bridge of a totally rimless frame, you’ll need to choose a very fine, thin wire frame; Silhouette will probably work well. The first objective is to remove the nosepads—not by unscrewing or unpopping them, mind you, but by snipping them off and finely sanding down the frame so as not to leave any nubs or rough patches that will irritate the wearer’s nose. A keen eye and a steady hand are essential here. You’re working against the very design of the glasses. If done successfully, you should have one long, smooth piece of metal, with no evidence of the nosepads you’ve just removed. The next step is to mold the bridge to the wearer’s nose, saddle style. While the crest of the nose is ideal, exactly where the bridge will sit is dependent on a variety of factors from the location of the breakage to the particular anatomy of this patient’s head. You’ll want the bridge to fit smoothly and snugly against the nose, roughly conforming to its shape. The next step is determining the shape and size of the lens. The advantage with using a rimless frame is that it allows you to determine where best to place drill holes in order to position the lens in such a way as to avoid placing undo weight on the patient’s nose while also providing excellent vision; the width of the lens will play an important role in determining how you adjust the temples to the sides of the patient’s head. You’ll need enough tension to hold the glasses in place while not exerting so much pressure on the nose as to make it painful or uncomfortable. Remember what we addressed above, in terms of nose pain not necessarily being caused by the bridge. The same holds true here—even if the bridge is well placed and formed to the patient’s nose, too much tension in the temples will pull it too tightly against the patient’s face. Make sure it’s snug enough to stay in position but loose enough not to hurt the patient. You may need to allow for a certain degree of slippage.

EACH DAY IS A LESSON

Of course, these three challenges only represent a fraction of the spectrum of possible unique situations an optician will face. There are patients with TMJ; patients with wildly asymmetrical ears; patients with unique nose shapes. Truly, while we may be able to abide by certain guiding principals, each patient is ultimately unique, shaped not just by biology but preference and life experience. The greatest lessons an optician can learn and apply in the school of apprenticeship are ingenuity, patience and creativity, to approach each situation uniquely.

Special thanks to Barry Santini for his advice and input regarding the broken nose section of this CE.