An Introduction to Low Vision

By Kara Pasner, OD, MS

Release Date: January 1, 2016

Expiration Date: January 20, 2021

Learning Objectives:

Upon completion of this program, the participant should be able to:

- Define "low vision" and its associated symptoms.

- List and define the common causes of low vision.

- Categorize and elaborate on types of low vision devices and their intended uses.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

Kara Pasner, OD, is an assistant professor of vision care technology at the City University of New York, New York College of Technology. She also maintains a private practice limited to low vision rehabilitation at four locations in New York and New Jersey.

Kara Pasner, OD, is an assistant professor of vision care technology at the City University of New York, New York College of Technology. She also maintains a private practice limited to low vision rehabilitation at four locations in New York and New Jersey.

Credit Statement:

This course is approved for one (1) hour of CE credit by the American Board of Opticianry (ABO). Technical Level II Course STWJH650-2

They say growing old is a privilege but growing up is optional. Regardless of how young we feel or act, age does take its toll on our bodies—our eyes notwithstanding. With age, there are ocular changes, which are considered "normal" and then there are changes, which aren’t. There are quantitative changes, such as a slight reduction in visual acuity, which are measurable in an eye exam. The other changes are qualitative changes, which are difficult to assess since they rely on a patient’s complaints. Usually they are complaints about a slight reduction in brightness, decreased contrast sensitivity, colors seeming duller and increased glare. These normal changes are relatively mild and can be perceived as an overall reduction in visual function—leaving some patients to say things like the familiar phrase, "I just don’t see as well as I used to."

LOW VISION OR LEGAL BLINDNESS?

When we speak about low vision, we are referring to abnormally large changes caused by things other than just age. So what exactly is low vision? Low vision has different definitions depending on who is defining it. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a range of visual acuity from 20/70 to 20/400 (inclusive) is considered moderate visual impairment or low vision. At its core, low vision is an uncorrectable vision loss that impairs one’s ability to function normally and perform the activities needed to live independently. The actual visual acuity causing this disability varies from person to person.

Results of the Lighthouse National Survey on Vision Loss (The Lighthouse Inc. 1995) indicated that there is great fear and limited understanding about vision loss and aging among older adults. Among persons age 65 and older, an estimated 21 percent report some form of vision impairment, representing 7.3 million people (Lighthouse International Survey 1995). As the population ages, the number of people with vision impairments that significantly impact their quality of life grows. Vision rehabilitation services are largely underutilized despite the need and benefit such services would provide.

Low vision should not be confused with legal blindness. Legal blindness is mainly used as a determinant of eligibility for government services. In the United States, it is typically defined as visual acuity with best correction in the better eye, which is worse than or equal to 20/200 or a visual field of less than 20 degrees in diameter. Total blindness is marked by a complete lack of light or form. Though many patients who are legally blind are low vision patients, the majority does not fall into that category.

EFFECTS OF LOW VISION

Signs of low vision interfering with normal activities can be subtle at first. People may notice that even with glasses or contact lenses, they have difficulty with tasks like recognizing familiar faces, reading, cooking, matching clothes, writing checks and watching TV. Lights may seem dimmer and glare harsher.

These could be thought of as early warning signs of eye disease. You might recognize these patients as the ones who "just can’t seem to see clearly" when you dispense their new glasses. By recommending a recheck, you may be saving a person’s remaining sight since at this point, it is important to seek the proper medical attention. The sooner treatment is initiated, the greater the chance of keeping the remaining vision intact.

These problems often lead to a gradual loss of independence and the ability to enjoy leisure activities like playing cards or hobbies. It is not uncommon to develop feelings of confusion, frustration, avoidance, isolation, fear and even depression. Ironically, these feelings can debilitate people and prevent them from seeking out and utilizing low vision care, leaving them to further spiral downward.

Most age-related vision loss occurs as a result of eye conditions like macular degeneration, cataracts, diabetic eye disease or glaucoma. Other contributing factors may be systemic diseases and the medications used to treat them. Each condition affects vision differently. Whatever the cause, lost vision cannot be restored. It can, however, be managed with proper treatment and low vision care.

LOW VISION IN THE AGING POPULATION: COMMON CAUSES

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) primarily affects the macula, the part of the eye that sees fine detail. Though it is painless, it gradually destroys the sharp, central vision needed for activities such as reading, sewing and driving. People describe it as a dark or empty area appearing in their center of vision. Sometimes, a person may tilt their head or appear to be looking at an angle; this is a way of compensating in order to use their remaining peripheral vision. AMD can also distort vision so that straight edges appear wavy. The primary risk factors are age, being female, Caucasian and a history of smoking.

Glaucoma is an eye disease in which the pressure inside the eyes slowly rises, causing damage to the optic nerve. This can lead to vision loss or even blindness. Glaucoma is treated with medication, lasers and surgery. As the disease progresses, a person may notice their side vision gradually failing; objects in front may still be seen clearly, but objects to the side may be missed. In addition, depth perception is often impaired. The primary risk factors are advanced age, positive family history and African descent.

A cataract is a clouding of the eye’s lens. Most cataracts start small and with time, grow larger and cloud more of the lens, decreasing visual acuity. This hazy, cloudy vision can make it difficult to read, watch TV, see food on a plate and travel safely. Some people complain of the appearance of spots in front of their eyes, bothersome glare from headlights or sunlight and colors appear duller.

If a cataract progresses and affects daily activities, surgery may be recommended. Sometimes, however, problems with other parts of the eye may prevent any improvement in vision after cataract surgery so removal may not be recommended, leaving people with permanently reduced vision. Age-related cataract is the most common type of cataract; though excessive exposure to ultraviolet radiation, smoking or the use of certain medications, are also risk factors.

Diabetic retinopathy occurs when new blood vessels grow on the surface of the retina. The longer a person has diabetes, the greater their chance of retinopathy. These vessels can bleed and impair vision, blurring side or central vision. Oftentimes, visual fields are affected as well. Therefore, other visual cues become important, namely contrast sensitivity, glare and color discrimination.

LOW VISION CONDITIONS IN THE YOUNG POPULATION

Though usually associated with the elderly, the low vision population encompasses people of all ages. In the younger population, vision loss can occur because of eye injuries, birth defects or diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa, Stargardt’s maculopathy, albinism and optic nerve abnormalities. People of middle age may experience vision and/or field loss due to the occurrence of strokes and traumatic brain injuries.

Children below the age of three should be referred to the state’s early intervention program. A multidisciplinary team of special education professionals will work with parents to enable the child to develop their abilities and potential. School-aged children who meet the criteria of visual impairment in their state are eligible to receive services from a certified teacher of students with visual impairments (TVI). They should receive instruction in literacy, visual efficiency, accessing the core curriculum, compensatory skills and more.

These patients are generally very active as they are of school and working age. The low vision devices, which will accommodate their needs, should be portable and practical for the settings they are in. It is also important to try to maintain a good cosmetic appearance, if possible, as it is an important consideration for this age group’s emotional well-being.

LOW VISION CARE

Low vision care tries to maximize any remaining vision through the use of various optical and electronic products. It is rehabilitation, not a cure. It should always be stressed that low vision aids do not restore the sight they once had. The people who are most helped have accepted their vision loss, have realistic expectations and goals, and are motivated to try to cope with their "new normal." By offering low vision care, we try to improve someone’s quality of life, regain some independence and allow him or her to live more safely. Many people can learn to make better use of their low vision and function efficiently with even small amounts of visual information. Practice, patience and proper training will go a long way in low vision care.

The ideal time to offer low vision services is as early as possible in the course of the disease. Early on, patients are more emotionally and psychologically stable and may be more motivated to try low vision aids. With mild to moderate vision loss, there is a larger choice of low vision aids available. These devices will usually be of lower powers with wide fields of view, which allows for more fluent reading as more words are seen at once. Ultimately, this makes it easier for most patients to incorporate the devices into their daily routines.

THE LOW VISION EXAM

The low vision exam has a different flow and focus than a conventional eye exam: less medical and more problem focused review of the activities of daily living that their diminished vision has made difficult. A detailed history should elicit clear and realistic goals such as "I want to read and/or watch TV better." The word "better" is key. Some patients think there are "magic glasses" that will restore their vision. Usually better is the best we can hope for.

The exam itself can be very long—often a full hour—and tiring for many patients. The refraction is carefully done with a trial frame and loose lenses. However, it is usual that glasses alone won’t help sufficiently. Further tests such as contrast sensitivity, visual fields and color vision will help determine the device best suited to meet the patient’s needs.

Low vision aids are like tools in a toolbox. Just as a workman requires different tools to complete different tasks, someone who is visually impaired may need a number of devices to perform various activities. It is best to categorize the aids into distance, intermediate and near demands and work on each area separately—paying most attention to the devices, which directly address the goals of the exam, as initially stated by the patient.

The initial determination of magnification needed is derived from Kestenbaum’s Formula: The inverse of the Snellen acuity is equal to the dioptric power needed to read standard 1M, newspaper size print. Further dividing the dioptric power by 4 will yield the magnification X. (E.g., 20/400 yields 20D, or 5X). Once the magnification required is determined, the appropriate visual aid(s) is selected, and the patient is trained in its use.

A complete exam also includes exploration of non-optical solutions to promote independent living. This can include suggesting products, which would enhance illumination, contrast and spatial relationships. A useful mantra here is "Bigger, Bolder, Brighter." Examples include lamps, reading stands, check registers, writing guides, bold-lined paper, needle-threaders, magnifying mirrors, high contrast watches and large print books.

Glare control can be a significant disabling factor in some conditions. Tinted lenses and visors are routinely prescribed. Absorptive filters are tinted lenses, which are used to counter glare. They come in different tints at various levels of absorption and different cutoff points for the visible spectrum of light.

MAGNIFIERS

There are several types of magnifiers, which can be recommended for the near demands of low vision patients. Available in a wide variety of designs and magnifications, many are also illuminated to provide additional light. All magnifiers come in different powers represented by an X or "times magnification." X is the ratio of the size of a magnified retinal image to the original image size.

The laws of physics and optics dictate that as the plus power of the lens increases, the diameter gets smaller and the center thickness gets greater. As the lens power increases the field of view gets smaller. This can frustrate many patients who require high magnification in order to see. The selection of devices must then balance the magnification needs with a field of view that will be tolerable.

Magnifiers can be found for purchase in many non-optical outlets such as craft stores, office supply and even some of the big box retailers. These over-the-counter (OTC) versions of hand, stand and spectacle magnifiers are often of a low power and aren’t strong enough to help individuals with low vision.

There are also qualitative differences in these products and the products sold by optical professionals. Some high quality magnifiers use a diffractive lens design instead of a simple refractive lens design, which makes the lenses up to 25 percent larger and about a quarter of the thickness of comparably powered refractive lenses.

Quality magnifiers are manufactured so that the lenses do not shrink or change shape in the manufacturing process. This helps to minimize distortion, making images seem clearer—an important attribute when the retinal resolution itself is poor. Sometimes, poor quality magnifiers display distortion in the lens periphery, making the outer border of the lens unusable and field of view effectively smaller so that only a few letters can be seen clearly at a time. This leads to a slower reading speed and makes comprehension that much more difficult.

Quality magnifiers have lenses with strong scratch resistant coatings on them to minimize scratching. This is important since most magnifying lenses are made of plastic. Scratched lenses can obstruct the view of what is being magnified and render the magnifier useless. Lower quality magnifiers generally do not have this and will scratch easily.

Another attribute of quality magnifiers is their use of superior illumination. The quality and positioning of lighting is an important factor that directly impacts image quality. Many patients use magnifiers that have built-in illumination, the most common type being the LED (light emitting diode). Proper regulation of the voltage provides a steady, strong light with minimal glare. They should last a very long time, and there are no bulbs that need replacing. They also draw very little current and therefore require infrequent battery changing.

The two main categories of magnifiers are hand magnifiers and stand magnifiers. Both are designed to help with short-term tasks that require working closely with the material. Typical uses may include reading newspapers, labels, mail, price tags and viewing dials or appliance controls. With both types, the magnifier has to constantly be moved to locate the required information (e.g., the bill total or start of a new line). Good control and the adoption of efficient patterns of magnifier movement are fundamental to user success.

Hand magnifiers are portable, relatively lightweight and can be used with or without glasses. The basic hand magnifier design consists of a lens on a handle. They are available non-illuminated or illuminated with incandescent lighting or light emitting diodes (LEDs). The lens itself can be designed as aspheric, aplanatic, biconvex or diffractive.

The distance between the eye and the lens is easy to adjust to improve focus and field of view. They are ideal for "spotting" tasks when a near object will be viewed for a short period of time. An example would be reading a medicine bottle, menu or price tag.

To use the device, a patient needs to put the magnifier on the page and lift it slowly until the print comes into focus. Once in view, the magnifier must be held at exactly that distance or focus is lost. It is important that these magnifiers are held with a steady hand—those with tremors may find handheld magnifiers difficult to use.

A stand magnifier is a lens mounted on legs or in a holder that maintains a set distance from the lens to the object. The lens itself can be designed as aspheric, aplanatic, biconvex or diffractive. Some have self-contained illumination. The magnifier sits directly on top of the text so it is always focused. The user simply glides the magnifier over the page. Additional magnification may be gained by bringing the magnifier closer to their eyes (relative distance magnification). Stand magnifiers are helpful for tasks requiring more fluent reading such as books and magazines. They are ideal for people who cannot hold a hand magnifier steady for long periods of time.

TELESCOPES/BIOPTICS

There are a variety of telescopes including monocular and binocular, focusable and fixed-focus, Galilean and Keplerian designs, handheld and spectacle mounted—all in a range of magnifications. Most help patients see at intermediate and far distances.

Sometimes called "monoculars," handheld telescopes are the most common type of distance optical device. They are inexpensive, small, inconspicuous, portable and focusable. They are held next to one eye for a short time as the patient spots things such as buses, faces and street signs. The patient must be stationary while looking through the telescope because depth perception and balance are affected, and they risk falling if used when mobile. Also, steady hands are important as even slight hand movements or tremors can affect the clarity of the image.

Spectacle mounted telescopes are devices that can be made as monocular or binocular models and are available in a range of magnification powers. They are a hands-free device and are therefore steadier than handheld telescopes. Usually, they are used for watching TV, seeing a stage (theater or church) or watching sport games. As with handheld telescopes, the user must be seated and cannot move around while wearing these telescopes.

Unlike other telescopes, bioptic telescopes are meant for mobile use. Small telescopes are mounted on the upper part of a spectacle lens. This placement allows the user to look through the bottom half of the lens while walking or driving and then drop their head and look through the telescopes to read a sign or identify a person. In some states, under strict conditions and proper training, bioptic telescopes can be used while driving.

ELECTRONIC AIDS

Incorporating technology into low vision has lead to an ever-expanding range of options to help people live more independently.

Personal computers and tablets such as the Apple iPad or similar tablet can be an excellent option for the low vision patient willing to learn how to use it. The high contrast screen, built-in accessibility features and downloadable apps for the vision impaired may make it an alternative to conventional magnifiers for some patients.

Screen readers are software programs that allow its users to read the text that is displayed on the computer screen with a speech synthesizer or Braille display. Most new computers come standard with assistive technologies like a built-in screen reader, screen and cursor magnification, and dictation (converts spoken words into text).

Also referred to as video magnifiers, closed circuit televisions (CCTV) have been available for decades and keep evolving. They use a video camera to capture an image of text and display it on a monitor. The text is on a table that is movable from the top of the page to the bottom and from side-to-side. The device allows a patient to magnify this image as much as is needed without the peripheral distortion of magnifiers. The brightness and contrast of an image can also be manipulated. Some products offer reverse polarity (white on black) and HD image quality. Most are compatible with any computer monitor. This is particularly helpful for writing tasks because a hand can easily fit under the camera and patients can watch themselves write.

Some CCTVs have additional features such as a swivel camera that can focus on objects at a distance that then can be viewed on a nearby screen. Another feature is the machine’s ability to read aloud whatever is placed on the reading tray, such as a letter, article or book.

Though CCTVs can be very helpful, they are limited in their practicality because of their high price point, bulk and size. In contrast, portable electronic magnifiers are moderately priced, small, handheld devices, which are easily transported. Many have high-tech features for enlarging and enhancing images, including an LCD light, a built-in camera, and a "freeze image" function for capturing magnified text and graphics. Overall, they are easy to use and extremely portable, making them a very popular option.

There are several apps designed for smart-phones that help the visually impaired with tasks like magnification, object recognition, money reading and color identification. Depending on how comfortable someone is with technology, this can be a viable option in low vision care. As the image quality and screens of many smartphones continue to improve and increase in size, smartphones may be able to take the place of handheld video magnifiers for some patients.

REHAB SERVICES OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY Occupational therapists are educated on disability and aging; they also have the appropriate background to address psychosocial issues related to vision loss, such as depression and lack of social participation. They can even apply for specialty certification in low vision (SCLV) from the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA, 2009) and will learn to teach adaptive skills like eccentric viewing, scanning and visual tracking. Occupational therapists also advise people how to modify their homes so they are able to perform the tasks they need to live independently. They will suggest solutions to problems like poor lighting, poor contrast and kitchen safety. They also will try to get rid of excessive clutter and other tripping hazards in order to prevent falls. In some cases, the occupational therapist can train a patient how to use their magnifier or visual aid properly as well. ORIENTATION AND MOBILITY

GETTING STARTED |

GETTING STARTED

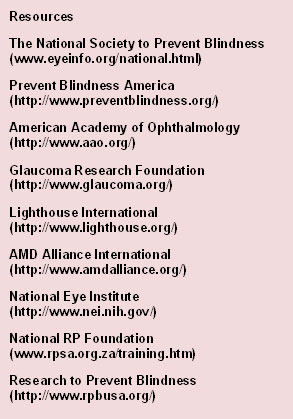

As with everything, the first thing to do is to educate yourself about the field. There are a variety of websites to get you started such as the National Eye Institute’s National Eye Health Education Program’s site, the American Foundation for the Blind, the Lighthouse International and Envision University. (See the online version of this CE at 2020mag.com/ce for a resource list.) If possible, spend a day with someone who works with low vision. Though learning about the conditions and the low vision aids is important, there is nothing like actually seeing it being done. It is a rewarding, fulfilling specialty whose demand is growing.