Probably no question elicits more surprise and emotion from eyecare professionals than when they’re asked: “Can I have a copy of my Rx and PD?” Why? Because this innocent request means they’re losing a bit more of their historical “control” over the sale of prescription eyewear. If we step back and take a longer perspective, we see that this query is just the latest manifestation of a consumer empowerment process that began more than three decades ago. In 1977, reacting to a rising tide of complaints that consumers were having trouble comparing eyewear prices because their eyecare providers were reluctant to give up their prescriptions, the Federal Trade Commission took decisive and corrective action by issuing Eyeglasses I, also known as the Spectacle Prescription Release Rule. Twenty-five years later, the FTC addressed a similar situation for contact lens wearers through the Fairness to Contact Lens Consumer’s Act. Importantly, both of these rules were designed to pry open an industry seen as unfairly acting in its own self-interest.

Fast forward to today, with the arrival of prescription eyeglasses offered online, and consumers find themselves once again squaring off for battle with their eyecare professional. This time, they’re asking their state officials for help in freeing their PD from their local eyewear establishment.

THE BATTLE FOR THE PD

Eyecare professionals argue that the pupillary distance is not a prescription parameter mandated for release under Eyeglasses I. Consumers counter that only by having the Rx and their PD will they be able to freely shop the eyewear market, which was the intent of Eyeglasses I. ECPs respond that by releasing the PD to a supplier outside their office, consumers are in essence removing them from responsibility as eyewear’s “general contractor,” leaving unanswered the question of who is ultimately accountable for ensuring product quality, prescription efficacy and overall visual comfort. Additionally, eyecare professionals admonish that by sourcing prescription eyewear online, consumers are separating out important try-on, consultative, fitting, warrantee and other services that form the majority of the added-value and increased cost represented in their higher asking prices. ECPs are seeing an obvious message here: If you pay less, you get less.

But as household discretionary income comes under greater downward pressure than ever before, consumers today are actively vetting the value they receive for every dollar spent. It’s no secret that the public views eyewear prices as arbitrarily high, and a recent CBS “60 Minutes” segment supports this sentiment. By referring to glasses as “just a few pieces of plastic,” reporter Leslie Stahl reinforced three things: 1. This phrase has great resonance with consumers. 2. ECP efforts to communicate their added value have been unsuccessful, and 3. Consumers willingly respond to seeing brick-and-mortar opticals as “greedy middlemen.”

THE NEW AGE CONSUMER

Striving to obtain maximum value, shoppers today are increasingly willing to experiment with making trade-offs to enjoy lower prices. But even as this new economic paradigm begins to impact the optical industry, most optical store owners have yet to begin to strategize how they will cope with this far more vigilant consumer. Unfortunately, by neglecting to outline even a simple fee schedule for servicing eyewear purchased outside their office, eyecare professionals have ended up creating a climate of resentment for both themselves and their patients.

Today, as a consumer’s desire to free their PD runs smack into an eyecare professional’s reluctance to hand it over, it’s time to take an in-depth look at all the issues surrounding this new skirmish. We’ll begin by exploring the business of making money in optical.

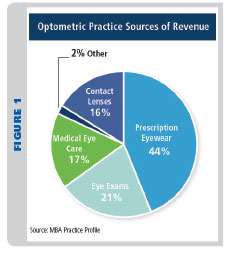

The business of eyecare is comprised by various revenue generators:

1. Eye Exam Fees—including diagnostic fees, up to 25 percent.

2. Procedure fees—various treatment regimens, including those for dry eye, eye training, vision training, etc., up to 20 percent.

3. Prescription eyewear and sunwear—eyeglasses can deliver up to 50 percent of the gross profits for most practices.

4. Contact lens exams, follow-up visits and replacement lenses—healthy practices can achieve 20 percent of their gross profits in this category.

5. Plano sunglasses and accessories—typically less than 5 percent of gross sales.

6. Eyewear service, repair and adjustment fees—yet to be determined.

Clearly the sale of eyeglasses is the greatest revenue generator for optical stores. But you can’t generally start the sale of glasses without first having an Rx. And Rx exams are financed primarily by participation in vision care plans (VCPs). For most consumers, the scheduling of exams and determination of eyewear allowances is initiated through the VCP’s logistics. With plan benefits usually timed to infrequent one or two-year intervals, it’s easy to see why leveraging an exam visit into a pair of revenue-generating eyewear is important. So when an Rx appears to be walking out the door, business owners see the single most important contributor to their bottom line walking right out with it.

With the attraction of low prices available online, consumers are beginning to question why their “trusted” eyecare professional is charging more for what appears to be the same product. And contained within that one word—product—is IMHO, the biggest mistake the optical industry has ever made. By bundling all the consultative, fitting, adjustment, warranty and other services into a one-price, product-centered transaction, ECPs did themselves and their patients a great disservice. Without a separate pricing schedule of services covering adjustments, minor repairs, replacement parts, warranty coverage, etc., included in the asking price of eyeglasses, consumers were left with only the eyewear product alone with which to compare prices and gauge value.

SMELL THE COFFEE

Ensconced within an insulated environment for years, ECPs had grown comfortable and complacent, with little motivation to face the realities of the changing marketplace. Although the arrival of big box chains in the 1980s did bring independents their first real taste of competition, ECPs were slow to begin adapting to the new disrupter in their midst. Today, new and alternate channels of distribution for Rx eyeglasses are beginning to spring up and capitalize on the ECP’s mistaken assumption that its customer base had always understood and appreciated all the services covered in the cost of their glasses.

POLITICS AND THE PD

The dispensing of prescription eyeglasses, a Class 1 medical device, has been regulated in part by some state requirements that a licensed optometrist or optician oversees the process of dispensing. Being a medical device, any records kept by ECPs are therefore considered medical records, and as such, must be made available to the patient on demand. Naturally, this could also include the patient’s PD. Even in light of this, consumers continue to encounter difficulties obtaining their PD when requested. Therefore, the question of what a consumer is rightfully entitled to in their eyeglass record is far from being conclusively answered. But as consumers become comfortable with buying other types of medical products online, they’re beginning to ask their government representatives whether the sale of prescription eyeglasses requires regulatory oversight at all.

PRODUCT SAFETY AND REGULATION

Product safety and efficacy are important concerns for both consumers and eyecare professionals. But the dispensing of eyeglasses by opticians, however, is still only licensed in less than half of all states. Although the FDA ensures that consumers face reduced risk from the consequences of compounded injury with the impact resistance requirement, they have not instituted regulations addressing the belief that eyewear lacking compliance with industry standards for power or PD can cause harm.

In our current regulatory environment, efforts to control costs and limit government involvement are constantly under scrutiny and review. Today, regulations are increasingly vetted toward optimal balancing of cost versus risk of harm. This is the main metric for determining the degree of oversight, regulation and recommendation for medical drugs, tests, procedures and devices. Notwithstanding anecdotes that ECPs recite about patients who needlessly suffered from poorly fitted or mis-fabricated eyewear, there remains a distinct lack of consensus or hard evidence of the risk of long-term harm accompanying poorly made eyewear. And hard evidence is what regulators need to substantiate hard regulation.

EVIDENCE-BASED RISK ASSESSMENT

In 2005, the Canadian Ophthalmological Society issued guidelines for the frequency of oculovisual examinations, including those exams intended to screen individuals for eye disease, provide secondary control of existing disease or tertiary prevention in reducing the consequential harm of chronic disease. In developing their guidelines, the COS employed real-world, evidence-based risk assessment studies. Here is a short excerpt of their surprising conclusions:

“Healthy adults, who do not notice anything wrong with their eyes, should see an eye doctor according to the following schedule: ages 19 to 40—at least every 10 years; ages 41 to 55—at least every five years; ages 56 to 65—at least every three years; and over age 65—at least every two years.”

Please note that within these same recommendations, the COS cited sufficient data to recommend at least one complete eye exam for children before age 5. Meanwhile in the U.S., only three states—Kentucky, Illinois and Missouri—have seen fit to mandate a complete eye exam before a child enters kindergarten.

EVIDENCE VS. BELIEF

Even with evidenced-based harm in hand, regulators today often find themselves coming into conflict with the public’s “common sense” beliefs about what constitutes acceptable risk.

For example, a few years ago, the New York State Commissioner of Motor Vehicles attempted to streamline the licensure process by reducing the DMV’s frequency of vision screening from once every eight years via a licensed eyecare professional to just a single test performed at initial licensure, with self-certification done at renewals thereafter. DMV officials in New York state had reviewed statistics from nearby Connecticut and Pennsylvania, who for years had been using a single vision screening done at initial licensure. While data is currently lacking that would help define the contribution of poor vision to car accidents, the real world evidence was clear: No statistically significant differences existed in accidents or injuries between states that regularly tested acuity and those that don’t.

As the Commissioner’s plan was unveiled, public pushback was swift and decisive: New York drivers did not want others sharing the road without a periodic vision test. Subsequently, the governor of New York instructed his DMV Commissioner to rescind the new proposed screening schedule and return to the previous eight-year screening model. Here, despite evidence of little risk, the court of public opinion had spoken loudly and clearly.

CHANGING ATMOSPHERE

If we look at the dynamics of oversight for prescription eyewear worldwide, we note how the regulatory atmosphere is changing with the arrival of online prescription eyewear. For example, in 2010, the Canadian Health Minister in British Colombia, responding to a court case involving a prominent online optical retailer, was prompted to review the current regulations concerning eyeglasses contained in the applicable Canada’s Health Professionals Act. Subsequently, changes were instituted to allow B.C. consumers to order eyewear online without providing the seller a copy of their prescription. The new regulations stipulated that all patients must be given a copy of their Rx for free—regardless of whether requested or not. Commenting on these changes, the Health Minister noted: “With advances in technology and more consumers turning to the Internet, it makes sense to modernize a decades-old system to give British Columbians more choice.”

THE END OF PRIMACY IN PD

With the legalization of the sale of over-the-counter reading glasses in the late 1980s, the decline in the importance of accurate pupillary measurement had begun. Some states tried to limit the perceived risks of OTCs by forbidding the sale of powers over 2.75 diopters. But is this anything more than a superficial gesture, based on a “feeling” that consumers needing stronger powers should be seeing an eye doctor? As far as the potential negative effects of inaccurate PDs in OTCs is concerned, a 2009 OTC reading glass study concluded that most spectacle wearers would tolerate “up to 0.50D vertical prism (imbalance) and up to 1.0D horizontal prism (imbalance)” without marked discomfort.

Today, as OTC reading glasses approach $800 million in sales and more than 46 million units sold annually (Source: Vision Watch 2012), it is clear that consumers are willing to trade imprecise centering in return for low price. With little hard evidence to the contrary, lawmakers are left with little choice but to continue to allow the sale of these “PD-less” reading glasses.

BEWARE OF PD BACKLASH

By resisting the release of prescriptions in the past, eyecare professionals discovered firsthand what happens when consumers profile them as unreasonably trying to control the sale of optical products. Recently, ECPs have attempted to re-close the system by carrying only those products or brands not readily found online. But in the case of contact lenses, where companies have touted to ECPs that their lenses are not readily available online, another backlash is brewing as consumers once again see ECPs trying to steer their freedom of choice. Although good practice management advises that ECP keep metrics on both capture ratio and prescription hand-off, these terms may, in an age of Internet transparency, invite misunderstanding if taken out of context by consumers. This could further impact ECP credibility.

The moral for eyecare professionals: Think twice before withholding a patient’s PD, even if state laws and regulations are on your side. We live in an era increasingly dominated by the power of social media, and the court of public opinion is not one to be taken lightly.

PD AND THE CONSUMER AS KING

In our political system, consumers are not always active participants. Nevertheless, government officials recognize their potential influence can be great if an issue surfaces with enough sizzle to stir voters out of bed on Election Day. It’s clear today that lawmakers increasingly tend to consider regulatory issues before them in “consumer-friendly” terms. In Utah, for example, legislation is pending that allows “alternate channels of distribution” for medical services that were previously done only by licensed professionals. There, as consumers increasingly feel comfortable taking their own blood pressure and heart rate in a kiosk at the local mall, lawmakers are considering that contact lenses and even eye exams could be made available in a similar manner.

Only a few states including Alaska, Arizona, Kansas, Massachusetts and New Mexico mandate that a PD be entered on every eyeglass prescription. But if eyecare professionals continue to ignore the growing demand for freedom of choice in buying prescription eyewear, they might just see their state officials become both consumer advocates and professional adversaries. More than ever, eyecare professionals must reformulate their business strategy to successfully compete in an economy where consumers are infatuated with the low prices, wide selection and convenience of online.

A Primer on PD Tech

Ask any eyecare professional if accurate PDs are important in satisfying an eyewear consumer, and they’ll no doubt respond with an overwhelming chorus of “Yes!” But hanging your professional hat on the hook of PD’s primacy today is a risky undertaking. To better appreciate a PD’s nuanced and multilayered character, let’s take a look at the science, anatomy and measuring techniques surrounding the pupillary distance.

PD FACTS

Quite a bit of research has been done into the science of pupillary measurement. The importance of needing to define the extremes, age and gender distribution of PDs can be found within the disciplines concerned with stereoscopic displays. Here, whether considerations are binocular or bi-ocular (two eyes sharing the same entrance pupil), knowledge of the range to be accommodated is essential in designing these devices. Because of this, almost all PD research concentrates on the importance of binocular rather than monocular values. Here is a short summary of their findings:

GENERAL RECOMMENDATIONS

- Extremes for all adults (Age 18 and over): 45-80 mm

- 95th Percentile for all adults: 70 mm and below

- Minimum values for children (Ages 0 to 5): 30-40 mm

- Mean and median adult PD (all races and sexes included): 63 mm

THE PD

- Changes most from birth to age 5 (up to 10 mm growth).

- Reveals second greatest change from ages 5 to 18 (up to 7.5 mm).

- Slowing in females at age 14; males at age 18, reflecting earlier female maturation.

- Average is smaller in females than males.

- Continues to change between the ages of 18 to 50 with most of the delta occurring in ages 18 to 30, and the average change is 3 percent.

- Changes more slowly in the age group over 60 (up to 1.2 mm).

THE METRICS OF PUPILLARY DISTANCE

THE METRICS OF PUPILLARY DISTANCE

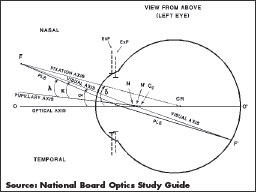

By definition, the taking of a PD suggests that we are determining the distance between the eye’s pupils. But within the last 20 years, as the optics and sophistication of eyeglass lenses have tremendously advanced, ECPs have started to improve their understanding of how designers use references beyond simple pupil location to help optimize a lens’ acuity, comfort and utility.

Pupillary axis: A line drawn perpendicular to the corneal surface through the center of the eye’s (entrance) pupil.

Visual axis: This is the actual sight line of the eye, running from center of the fovea, through the eye’s nodal points and out to the object of regard. This is where the brain is actually looking. Because the fovea is displaced temporally from the intersection of the pupillary axis with the retina, the corneal reflection axis is normally found approximately 3-5 degrees nasal of the intersection of the pupillary axis with the cornea. The angle between these two axes is known as angle kappa and has linear values at the respective corneal and spectacle planes (VD = 13 mm) of approximately 0.25 mm and 0.50 mm.

Corneal reflection: Also known as the corneal reflex, it is the image formed by a light source shining upon the cornea. If the examiner is co-axial with this light source, then the position of corneal reflection marks where the visual axis exits the eye. This is important for determining prismatic effects and optimizing placement of a progressive lens’ intermediate corridor.

Center of rotation: This is the virtual point around which the eye appears to rotate during its excursions. Its importance in lens design is twofold: It allows designers a proper reference for optimizing a lens’ off-axis performance, and it is essential for maximizing binocular performance within a pair of lenses. A line drawn from the object/fixation point through the CR (center of rotation) is called the fixation axis. The CR provides a stable framework for the comparison mapping of corresponding points on each eye’s retina. Specific equipment, Rx parameters and other anatomical factors are required to assess the precise location of the center of rotation.

MEASURING PD

For eyecare professionals, it wasn’t until the arrival of progressive lenses in the 1960s that the importance of an accurate monocular PD for obtaining optimal intermediate and reading utility was fully appreciated. Before that time, measurements primarily centered on obtaining binocular PDs. Using a millimeter ruler, monocular values, if desired, were derived by halving this value.

MEASURING METHODS AND ACCURACY

Several studies in the last 20 years have attempted to scientifically analyze the accuracy and repeatability of obtaining PDs using three primary methods:

- PD ruler: Used to measure the distance between pupils, corneal reflections, iris margins and particularly in the case of small children, the inner and outer canthus. A study completed in 2002 assessed that the ruler method can yield values accurate to within 1.54 mm of a “gold standard” (see below) with 68 percent confidence.

- Pupillometer: Primarily measures the distance between corneal reflections. Overall values were found to be within 0.74 mm accurate with 95 percent confidence.

- Digital centration devices: These may use either corneal reflections or iris borders for determining PD. The user should be aware if the device’s software employs an internal calculation to extrapolate at the visual axis location from the pupil/iris center. DCDs were found to be very accurate instruments, with binocular PDs found to be within 0.40 mm with 95 percent confidence.

There’s a pattern here: Pupillometers appear more accurate than millimeter rulers and digital centration devices appear more accurate than pupillometers. But before you ditch your PD ruler, remember that the ruler and manual measurements will always play an important role in an ECP’s toolkit. Both objective and subjective verification and trouble-shooting of prescription eyewear will continue to require expertise in the use of ruler and pen. Because of this, some practitioners prefer to use an enhanced manual method, which employs a mirror to subjectively determine the visual axis at the spectacle plane. Each method has to consider variables that may impact accuracy and efficacy. Below is a summary of the most important factors affecting pupillary measurement:

- Device calibration: While obviously important when using instruments, parallaxic errors can arise when using the ruler method if there are differences between the PDs of tester and subject. These are avoided by using Jalie’s Rule of Sixteenths, which states that every millimeter difference PD requires an adjustment of one-sixteenth millimeter to the end result.

- Instrument operator skill/experience:

- Repeatability—can a single operator take several similar measurements from the same patient?

- Serial—can multiple operators take similar measurements from the same patient?

- Near and intermediate considerations:

- Vertex distance—generally based on an average value of 13 mm. However, if the fitted VD departs from this number by 4 mm or more, then values for near and intermediate use will not be optimal without recalculation.

- Pantoscopic tilt—improperly measured values can result in deviations that may require compensation.

- Frame considerations: A person’s physiognomy or fitting preference may place the frame markedly off the facial median plane, a deviation that can make the efficacy of the found values suspect.

- Head cape: Defined as the habitual departure from the orthogonal facial plane, head cape compensation is important for both optimal binocularity and multifocal utility.

- Rounding errors: Present in all methods, rounding errors can affect accuracy.

- Patient cooperation: This is one of the least controllable of all variables affecting PD measurements.

THE GOLD STANDARD IN PD

In the 2009 study, eight different devices, both pupillometers and DCDs, were used to help answer an important question: Considering all the variables affecting a PD measurement, can we be confident that using any method or instrument will result in the complete truth of a precisely accurate PD? The answer is no. Faced with determining the truth of an objectively unverifiable parameter, statisticians often turn to averaging all the measurements to a mean value, and then observing the distribution of all the values found to this mean. This “best possible compromise” is then referred to as the gold standard. The 2009 study sought to establish both device repeatability (nine subjects tested in five rounds by eight different instruments) and serial consistency (80 subjects measured once by eight different instruments). When the data was adjusted for various corrective factors, the average for all devices was found to be within 0.6 mm of the gold standard with 95 percent confidence. That’s accuracy I’d take any day.

—BS

L&T contributing editor Barry Santini is a New York State-licensed optician based in Seaford, N.Y.