Photograph BY NED MATURA; Frame: VAN HEUSEN STUDIO S360 from Nouveau Eyewear

By Palmer R. Cook, OD

It could be the milk spilled at breakfast, slow traffic on the way to work or the phase of the moon. The reasons are countless and largely unavoidable, yet things happen that disrupt our best intentions. We want our patients to have error-free eyewear, but mistakes occur. The eyewear order, ready to be released to your lab, is the point at which the data is consolidated. It is the best point for heading off errors before they cost you in time, reputation and money. This final check of the order should be for far more than clerical errors.

THE IMPORTANCE OF PROTOCOL

Every practice has an ordering protocol for lab work. The protocol may be carefully planned and pruned, or it may be a habit-task that grew by trial and error. Planned and pruned is better. Trial and error is costly at best, but planning pays off, and errors deserve analysis if you want your protocol to improve and function in the best possible way.

A protocol is a system of rules, and even if only one person does the lab orders, a written protocol should be in place. To minimize errors, everyone should follow that same protocol for ordering. When standardizing your ordering, it’s a good idea to ask your staff to describe when they do it and how they do it. Their information should include comments or suggestions.

We are creatures of habit, and chores that are done at the same time every day are somehow less burdensome, and they are usually carried out with fewer errors. That’s not to say that ordering cannot be worked into nooks and crannies that occur in your office schedule, but handwritten or electronically-created orders may have fewer errors if you can find a “same-time, quiet-time” for creating them.

WHY IS VERY IMPORTANT

Once you have collected tips from the staff on ordering, be sure to ask, “Why do you do it that way?” This question can open a gold mine of great information. “I always record the patient’s name first, because if I get interrupted before I finish the order, it’s faster and easier to match that order to a scrip or to a patient’s record,” warns you that interruptions happen, and it is a method with an apparently valid basis. So use it as part of your standard protocol.

“I write -1.00 for a minus lens, but I just skip the sign and write 1.00 for a plus lens of that power.” Omitting a sign is a shortcut, and busy employees love shortcuts, but this is a shortcut that saves little time. It may work for staff members who are very detail conscious, but it might not be a good idea for all, so in the interest of standardization, using a plus sign should probably be your rule.

FOUR EYES INSTEAD OF TWO

Recently I intended to order a centration chart. A day later I reviewed my email request only to discover that I had requested a contraption chart. My own proofing of the message missed the error. When I sent an apology with a corrected request, I intercepted my Spell Check’s blundering insistence that I wanted a contraption chart rather than a centration chart. Every editor knows the importance of a second set of eyes. When we are sure of ourselves and totally experienced with our subject, we tend to read what we meant, not what we put on the paper or on the screen. Two sets of eyes on every order will reduce errors and remakes.

If the second set of eyes can be the prescribing doctor or an office manager who is well-versed in optics, your protocol becomes a management tool. For offices that primarily fill prescriptions generated on-site, there should be a protocol of the examining doctor making (and sharing) lens and frame recommendations that the optician can use in eyewear design. This is another “protocol topic” that is hugely important and that is probably intuitively understood by every experienced optician. It increases patient confidence and satisfaction, and it avoids time-consuming issues in eyewear design. If the person proofreading orders has a “recommended by the doc” list to compare to the order, it may be easy to identify any need for educating and supporting the staff members who are helping patients with eyewear design.

WHO-DUN-IT

Your protocol should call for the ordering staff member and the order proofreader to initial or sign off in some recognizable way on each order before it goes to the lab. This assures the order is complete and ready to go. It can significantly shorten the time and effort needed to straighten out errors and omissions. Everyone makes mistakes. That’s just how life is, so be careful to avoid creating an atmosphere of paranoia and guilt over ordering errors. When errors happen, structure your protocol for resolving them to be as efficient as possible—it will make for a healthier office culture.

ORDER AND EFFICIENCY

When checking an order on paper, your first action should be to pick up a pen. Make a small check on each item of the order including the blank areas. If you don’t have hard copies of your orders, you might consider routinely printing out one for the patient’s record or job tray. If there are lab delays, the information can be noted for quick reference if the patient calls. The checks can be put there. They are your guideposts for not missing omissions. ■

In addition to clerical errors, there can be critical measurement, optical and eyewear design problems that are easy to miss:

1. For non-PAL orders, a very common error is failure to specify the height of the Major Reference Point (MRP) or optical center (OC). In most cases, the patient tolerates this error, but you are not giving the full value of the lens technology. This error is so common that nearly every lab uses some rule for placing the MRP or OC height even though this gives compromised performance for many patients. If you want to rate “top shelf” in terms of patient satisfaction, every order should have a Fitting Cross height or an MRP height.

2. Another common error for all prescriptions, including PALs, is choosing an inappropriate lens material. All prescribing doctors should have a good understanding of lens materials, but they often do not specify a lens material as part of the prescription. This is because both the eyesize of the frame and decentration are important factors in selecting the lens material. Using an inappropriate lens material is very frequently the underlying factor when patients return with complaints about their new eyewear.

3. The decentration is a quick and easy calculation that should be done before the frame selection is finalized. Decentration ideally should be inward from 1 to 3 mm in each eye. Adding the frame eyesize to the DBL (sometimes called the bridge size) and dividing the result by 2 gives the frame’s monocular PD. For a 50 n 20 frame, the monocular PD is 50 + 20/2 or 35 mm. If the patient’s monocular PDs are 34, 33 or 32 mm, you are on pretty safe ground. Outward decentration (i.e., the frame monocular PD is less than either of the patient’s monocular PDs) can create optical problems and should be avoided. Decentration should be carefully checked on every lens order.

4. Centration charts should be used for every PAL order. Failure to do this is a common cause for patient problems and remakes. If a patient is falling in love with a frame during eyewear design, do a quick check with the correct centration chart before the patient-frame relationship becomes serious. Your protocol should include a code (e.g., CC) on the chart or order to show that a centration chart was used. The best place for using centration charts is at the eyewear design table.

5. The height of the Fitting Cross should exceed the manufacturer’s minimum fitting height by at least 2 or 3 mm. When fitting at the minimum fitting height, you are eliminating the lower half or more of the reading area of any PAL. Bumping up the power of the add will not work, but raising the Fitting Cross height might. Most patients will better tolerate dropping their chin a bit for distance viewing than losing half or more of their reading area. The minimum fitting height was developed as a marketing concept and is not needed if you use a centration chart before ordering.

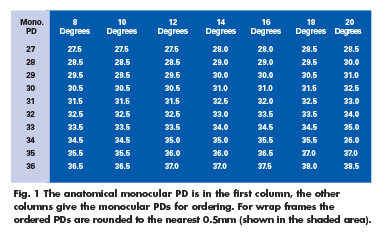

6. Know and abide by your lab’s rules for using wrap frames. Some base curves and powers just won’t work well with wrap frames and your lab knows it. When using frames with 10 degrees or more of wrap, include: “Special Instructions: Correct for wrap please.” Your lab should both adjust the PD (somewhat greater) and include some base-in prism for wrap mountings. This prism is even needed on plano lenses unless the front curve is plano. You can make the needed PD adjustment or the lab can, but be sure only one of you makes this correction. (See Fig. 1)

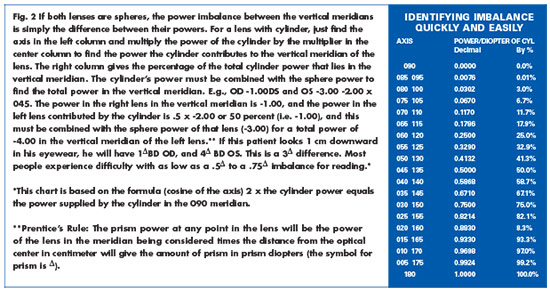

7. Imbalance can cause a binocular patient to see two, instead of one image with their new eyewear. Most patients find this unsettling, and they may quickly lose confidence in the care you provide. Lower amounts of imbalance, around 0.5, may not cause diplopia, but may result in complaints of discomfort, tiredness around the eyes and prolonged adaptation issues.

Whether your practice is a multi-doctor, multi-location business or smaller with only a few staff members, establishing protocols for key parts of your operation will make your day run smoother and increase patient satisfaction and confidence.

COMMON CLERICAL ERRORS

1. The patient’s name is illegible or omitted entirely.

2. “Tint” is marked, but the kind, the density or both are not listed.

3. Contradictory instructions are given such as a UV blocker is ordered for a lens that will block UV inherently, or a 2-mm center thickness is specified for a +5.00DS with a 50-mm eyesize. The minimum edge thickness of a plus lens can be controlled, and the center thickness of a minus lens can also be controlled. But be careful what you wish for as the saying goes (see number 9). The diameter and the laws of physics and geometry limit the minimum center thickness of a plus lens.

4. Only one or two digits are used for the orientation of the axis. The axis of any cylinder should be written with three digits. An axis 15 instead of an intended 115 or 150 might result if the pen skips or an interruption occurs.

5. “Frame to Follow” is marked but the name of the frame and its color are omitted. This slows down your order and complicates matching the frame to the order when it arrives.

6. A frame that needs to be matched to an order arrives without the patient’s name or other identifying information.

7. Lens powers are filled out but the power signs (plus or minus) are missing. This entails a phone call, fax or email, all of which slows down your order, not to mention the time your staff loses in sorting things out and responding.

8. Inappropriate edge thicknesses are specified for grooved plus lenses. Some materials are not appropriate for grooving. Both poly and Trivex accept grooving well. Other materials are more prone to chipping or flaking, depending on the edge thickness and curvatures. Usually a 1.8 to a 2-mm minimum edge thickness is advisable for grooving.

9. Inappropriate center thicknesses are

specified for minus lenses. A too-thin center reduces impact resistance and leads to warping that reduces optical performance.

10. The PD information is not included. (Review number 7.)

11. The staff member who placed the order is not identified. If questions arise, it often speeds things up if the lab knows the name of the person most likely to be able to answer questions. Frequently this proves to be the person who placed the order.

12. The selected frame is inappropriate for the lenses. Because of issues of lens power, thickness and curvature, every frame will not work well with every prescription.

13. The name of the frame on the order is not the same as the frame that is submitted for lenses.

Contributing editor Palmer R. Cook, OD, is director of professional education at Diversified Ophthalmics in Cincinnati, Ohio.