It is amazing to me that no matter how long a person has been in this field, you will always see something new. Today was one of those days. A young lady, age 16, came in for a routine eye exam. I had seen her in 2015, and there was nothing of concern at that time. She was slightly hyperopic, visual acuity was corrected to 20/20. Eyes looked healthy, no problems.

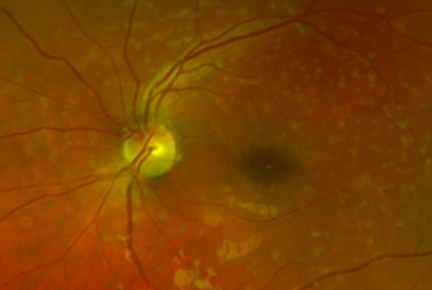

This year was different. The young lady came into the office with a chief complaint that she plays the saxophone but can’t see to read the music anymore. She was still showing a slight prescription, but best correction was 20/60. The patient was dilated, and fundus photos were taken. What we saw was surprising. Upon retinal evaluation there was the presence of small, yellowish spots of drusen. This deteriorating tissue was sloughed off from the outer layer of the retina. It has a similar appearance to macular degeneration. But in a 16-year-old?

The optometrist knew exactly what we were dealing with - Stargardt’s disease. I learned that Stargardt’s is an inherited disorder of the retina. It is normal for vision loss to begin during childhood, but it is rare that a person will become blind. There is a slow loss of central vision in both eyes. They may be more light sensitive than others. Also, color blindness can be a result later in the disease.

The retina contains light sensing cells called photoreceptors. There are two types of receptors, rods and cones. These receptors detect light and convert it into electrical signals. Rods are found in the outer retina and help a person see in the dark. Cones are found in the macula and help us see color and detail. Both the cones and rods die away with Stargardt’s disease.

Stargardt’s is inherited. Genes are bundled together on structures called chromosomes. One of each chromosome is passed by a parent to their child. In autosomal recessive inheritance, you inherit two mutated genes, one from each parent. When two carriers have a child, there is a one in four chance the child will have the disease, and one in two chance the child will be a carrier. My optometrist broke the bad news to this young lady and her family. With a little research by the family, they found there is a family history of this disease; her paternal grandmother, aunt, and great uncle were all diagnosed.

The patient showed edema or subretinal fluid. There were Pisciform lesions on both maculas. These lesions are round or dot- like, and yellow to white in color, typically found in Stargardt’s patients. The retinal specialist recommended 30-2 visual field testing and genetics testing. All the testing can be rather expensive so it may take some time. She scheduled a two month follow up appointment with the retinal specialist for a dilated exam and fundus photos.

After her retinal examination, the patient and her family returned to the clinic. We filled a mild glasses prescription to correct her astigmatism and give her the best vision possible. She seems to be in good spirits. We will continue to follow up with her care, and hope for the best. You can learn more about low vision and its other causes with our CE, An Introduction to Low Vision at 2020mag.com/ce.