By Palmer R. Cook, OD

At one time, ordering spectacle lenses from a lab meant selecting an appropriate frame, copying the lens powers onto a form, specifying one of two materials (crown glass or standard plastic), filling in a distance (and sometimes a near) PD along with the frame size and tint (if any), and the job was done. For most prescriptions, only the skills of a salesperson or clerk were needed.

Although these skills are still important, ordering lenses today requires much more. That’s because today’s improved lens technology, despite its many benefits, has also made it more complicated to achieve the best possible vision and comfort for patients.

For example, 98 percent or more of prescriptions can be filled using any one of seven lens materials, and as a result, selecting the best material for your patient has become no small task. To complicate things further, there are multitudes of lens designs, tints and treatments available to improve eyewear performance. Your goal as a dispenser is to create eyewear that allows the patient to see well, look good, be comfortable and realize the best value in their ophthalmic purchase. The lens Rx is just a springboard to get you in the air, so to speak; how you land is more than ever dependent on your own knowledge, experience and skill.

A 90-second screening for errors and omissions can drastically reduce remakes and help you avoid non-adapts. It can also reduce patient disappointment, make adaptation easier and improve word-of-mouth (i.e., what “they say” about you and your practice).

The following checkpoints are guides to make screening orders quick and easy:

1. The Major Reference Point (MRP) height is not specified on non-PAL orders. MRP heights should be given for all single vision, bifocal and trifocal orders. The MRP is that point in the lens that gives the desired Rx. Your patients get the maximum benefit of the purchased lens technology when their lines-of-sight pass through the MRPs for straight-ahead, distance viewing. Labs report that more than 95 percent of non-PAL orders do not specify an MRP height. As a result, labs all have a “standard” MRP height that is usually at the mounting line for SV, or 3 to 5 mm above the seg lines. If you are meticulous about the PD (i.e., the lateral location of the MRP), why not be equally concerned about the vertical positioning?

2. The lens material is not appropriate. Inappropriate choice of the lens material may be the single most common cause for patient dissatisfaction with their lenses. The inappropriate index selected is often too high. A “too high” index increases cost and decreases optical performance. A “too low” index increases lens volume and thickness. The lightest material for lenses between about -10 and +12 is Trivex from PPG Industries. The thinnest lens would be made from the highest index material available. Practically speaking, the thinnest lens may not be the lightest, and its optical performance can be problematic. The lens with the least reflectance would be made with the lowest index available.

Chromatic aberration is material-related and prism-related. It causes little problem for spectacle wearers when they look only through the optical center of the lens, but it can be distracting when the wearer is looking through the periphery of certain lenses. A good rule-of-thumb is to divide the power in the horizontal lens meridian by the Abbe value. Any prescribed prism power in the horizontal meridian should be added to the lens power before dividing by the Abbe value. This gives the dioptric spread from red to blue light at a viewing angle of about 20 degrees. This could be called the Abbe Index. The Abbe Index easily benchmarks a material’s suitability for any Rx. If the Abbe Index is about 0.125 diopters or higher, the patient may experience problems (especially out-of-doors).

3. Inappropriate decentration is a red flag for potential problems. Lenses should never be decentered outward. For most prescriptions, a 1 to 3 mm inward decentration is a reasonable rule. Outward decentration from the geometric center of the eyewire creates unwanted optical issues, and excessive inward decentration increases weight and unwanted prism related problems.

4. Higher index material is specified for low power lenses. Lower index lens materials generally give better overall optical performance, and they should be used for low and moderate powered prescriptions unless there are other overriding concerns.

5. Anti-reflective lenses are not specified. Anti-reflective treatment improves the performance of every lens material and every prescription. If anti-reflective lenses are not used, you better ask yourself and your optician, “Why?”

6. Choosing an inappropriate frame can cause many difficulties. A patient with a +6.50 Rx may be disappointed when the frame (“It looked so nice in the plano ‘display’ lenses.”) is fitted with their own Rx lenses. Placing a high plus lens in a frame with a nylon-cord mounting system may increase lens thickness, weight and magnification. Some frames will not easily accommodate lenses with steep base curves, and other frames are specifically designed to hide the thick edges of high minus lenses or reduce the center thickness and magnification of high plus lenses.

7. A power imbalance exists between the vertical meridians of the lenses of 1.25 diopters or more for bifocals, trifocals or PALs. The amount of acceptable imbalance varies depending on the patient’s sensitivity and the lens design. For lined lenses, 1.25 diopters of imbalance or more may be enough to cause difficulties, and with PALs even lesser amounts of imbalance can cause reading difficulties. Using a shorter corridor tends to help in borderline cases of imbalance. Even single vision lenses with greatly varying power between the right and left vertical meridians can cause problems unless the MRPs are placed correctly.

8. Improper placement of the fitting cross can spell real trouble on a PAL order. The minimum fitting height is available for almost all PAL designs, but if the minimum fitting height is used as the Fitting Cross Height (sometimes called the seg height), half or more of the usable reading area of the lens will be lost. Some patients may be satisfied with this, especially if they have small pupils, but most will not. Centration charts, which are available for all major lens designs will help you avoid such problems. By keeping a notebook with a laminated centration chart for every design you use, you can quickly and easily verify the patient’s choice of frames. Marking a “CC” on the order verifies that the centration chart was used, and a “CC” on all PAL orders will reduce patient problems.

9. Lenses mounted in wrap frames with no special instructions may lead to problems. When a lens is tilted around a vertical axis, BO prism is created. Base-in prism must be created to neutralize the prism effect. High-end, plano sunglasses usually include this prism to make them more comfortable. It can be easily measured in a lensmeter. The refractive power of the lens also changes. Your lab should be aware of this effect also and can correct for it if you simply note, “Correct for wrap, please” under Special Instructions.

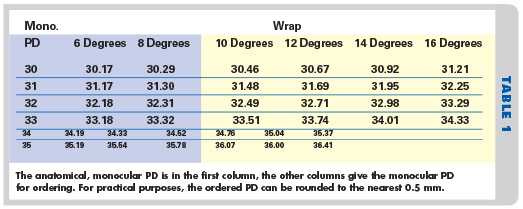

A third effect of wrap is the introduction of PD errors. Table 1 (above) gives the monocular PD to order with anatomical PDs from 30 to 35 mm when wrap frames of varying degrees are used. The amount of increase can be rounded to even half millimeters. Increases that round up to 0.5 mm or more than the anatomical PD are shaded. This PD correction is often overlooked by labs, and it is often not included along with the other wrap prism and power corrections.

10. Prescribed prism with odd combinations of the bases may spell trouble. For lateral prism, the direction of the base is usually “In” (BI) or “Out” (BO) in both eyes. For vertical prism, the direction of the base is usually “Up” (BU) in one eye and “Down” (BD) in the other. This rule is legitimately broken for very good reasons, but it holds true for 99 percent of lens orders.

11. Question cylindrical components with only a one or two-digit axes. Often it’s the simple stuff that trips things up. Remember the Hubble Space Telescope fiasco? That might have been avoided with a little more attention to vertex distance. If the Rx is plano -2.00 x 018, it should never be written plano -2.00 x 18. Why? A moment’s distraction could have occurred and perhaps 180 or 118 was intended. This sort of thing happens, and the result can be embarrassing and expensive. Somehow we are more careful about powers. It’s unlikely that anyone would write it plano -2. x 018.

12. No date, no initials is simply incomplete. It is only good business to be able to quickly identify both “when” and “who.” It only takes a moment to date and initial an order when it is written, but if questions arise, getting a quick unraveling of the problem may be difficult if the information is not on the order.

13. Unintelligible handwriting can delay your order. If the handwriting is truly unintelligible, you will get a call from your lab, or the order might get set aside and delayed. “Subject to ambiguous interpretation” is probably even more important, because a misread number or comment can lead to receiving, and even dispensing, a totally incorrect set of lenses.

14. Measurements are missing. Thanks to digital technology, we can tailor lenses to maximize performance. All of the publicity, advertising and education that have been made available over the past few years have led some ECPs to feel that they cannot take adequate measurements. Manufacturers provide default or “average” measurements that can be used to fill in the blanks, but that makes about the same sense as using average PDs. Using default measurements means that someone is cutting corners, or perhaps they need training to take measurements with confidence. There are many tools now available for taking measurements. Some are relatively inexpensive and some are not, but unless those tools are used routinely and correctly, your practice will not be able to provide the best in eyecare and eyewear.

PHANTOM COSTS

It should be apparent that errors in ordering can cost you money and affect your professional reputation, but you may only be aware of the tip of the iceberg. There are “phantom costs” associated with ordering errors. These are the errors you seldom if ever see, but they cost you dearly nonetheless.

Patients who have difficulty with new eyewear may not be comfortable returning with complaints. In fact, they may not return at all, but human nature being what it is, they may share their difficulties in ways that can negatively affect you and your practice.

All ophthalmic labs are aware that re-makes are sometimes unavoidable, so they generally structure their fees so they can do re-makes at a reduced cost, or occasionally even at no cost. But it is a cost of doing business that you and every other ECP must either absorb or pass on to the public.

All ECPs have had patients return with adaptation problems. But were the adaptation problems really adaptation? Improperly designed and fabricated eyewear can often be worn more or less successfully because our bodies and our perceptual systems are so adaptable. When patients let you know that adaptation to their new eyewear is difficult, you should make every effort to resolve their problems. Crossing your fingers and telling them just to wear them should only be done when you have exhausted every other resource.

REAL BENEFITS

By screening your orders with another set of eyes, just as a writer vets his copy with the help of an editor and proofreader, you can reduce remakes, costs and patient difficulties. The one person who should not screen orders is the person who wrote the order. This is for the same reason that writers should not be the proofreader for the letters they write. A second set of eyes will always discern errors and omissions more easily, and that second set of eyes should be able to do the above 14-point checklist in about 90 seconds, after a little practice. The final benefit is that the order writer and the checker will have a learning curve related to the fact that each of the 14 points (with the exception of 11, 12 and 13) can and perhaps should be violated under special circumstances or in order to meet patients’ special needs.

Contributing editor Palmer R. Cook, OD, is director of professional education at Diversified Ophthalmics in Cincinnati, Ohio.

The Abbe Value/The AbbE Index

The Abbe value is a well-established, scientific term that is recognized industry-wide. The Abbe Index is suggested here as a useful in-office tool for designing eyewear. It gives you a guideline to help in determining whether the patient will have problems related to chromatic aberration. Some patients may not notice the effects of a 0.13 or a 0.15 Abbe Index, particularly if they are viewing objects at distances of 20 feet or less. Others may be more sensitive.

You can calculate the Abbe Index in the meridian of strongest power, or you may want to calculate it in the horizontal meridian, since most of our eye movements are in that meridian. Any prism in the meridian you choose to consider should be added to the power in that meridian. For example, a lens that is -5.00DS with 4rBO would be calculated in the horizontal meridian as (5 + 4)/the material’s Abbe value. If the Abbe were 30, the Abbe Index would be 9/30 or 0.3 diopters of image spread from red to blue. This is the image spread or blur that would occur when the patient looks about 20 degrees to his or her left or right. If the prism is vertical, the Abbe Index would be 5/30 or 0.167.

The Abbe Index does not take the viewing distance into account, but patients find a high Abbe Index more troubling at longer distances. Strangely, this is one optical formula in which you can add refractive power and prism power with impunity.

—PRC