|

Etiologies

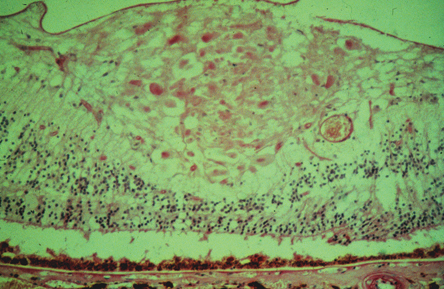

Early light microscopy of cotton-wool spots in the retina revealed the presence of a so-called cytoid body, a round dark staining "nucleus" within a grossly swollen nerve fiber layer (See Figure 2). It was not until the application of electron microscopic techniques that the "nucleus" of the cytoid body was identified as an accumulation of intracytoplasmic organelles interrupted in their normal slow and fast anterograde and retrograde transport between the ganglion cell bodies in the inner retina and the terminal nerve endings in the lateral geniculate body. Due to the strong association with microangiopathic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and systemic hypertension, the interruption in axoplasmic flow in cotton-wool spots is thought to result from focal ischemia associated with occlusion of precapillary arterial flow, though other possible etiologies have also been suggested.

Diabetes mellitus and systemic hypertension are by far the most common cause of cotton-wool spots. In patients who have a cotton-wool spot and no known history of diabetes, an elevated blood sugar level is identified in 20 percent of patients and an elevated blood pressure (diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or greater) in 50 percent of patients.1

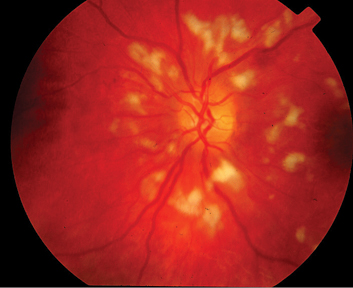

Patients with diabetes mellitus might also harbor other typical retinal findings such as macular edema, retinal exudate, flame or dot/blot hemorrhages, microaneurysms, venous beading or microvascular abnormalities or proliferations. Conversely, patients with systemic hypertension would be expected to demonstrate generalized arteriolar narrowing, arteriolar/venous nicking and, in extreme cases, optic-disk swelling.

|

In addition to systemic hypertension and diabetes mellitus, cotton-wool spots may be found in numerous other diseases. These diseases can be generally divided by cause into ischemic, embolic, infectious, toxic, radiation-induced, neoplastic, tractional, traumatic, immune-mediated and idiopathic causes.

Ischemic disorders that can result in cotton-wool spots include retinal vascular occlusions, ocular ischemic syndrome and severe anemia. Embolic disorders that can produce focal inner retinal ischemia may arise from cardiac, carotid or deep venous sources, as well as intravenously injected foreign materials, such as talc.

In addition, white cell emboli from long bone fractures or pancreatitis following thoracic and/or abdominal trauma can occlude precapillary arterioles, resulting in dramatic cotton-wool spots and hemorrhages seen in Purtcher's retinopathy.

Infectious diseases, such as HIV, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, cat-scratch fever (bartonela henslae), leptospirosis, onchocerciasis, or diseases that result in a bacteremia or fungemia may also produce cotton-wool spots. Retinal microvascular occlusions may occur after the use of interferon or other chemotherapeutic agents, and/or radiation exposure, both of which share a similar mechanism of action on endothelial cells.

Neoplastic disorders such as lymphoma, leukemia and metastatic carcinoma may also be associated with cotton-wool spots. Collagen vascular/immune complex diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosis or cryoglobulinemia may also result in occlusion of precapillary arterioles.

Mechanical Distortion

|

In addition, traumatic laceration of the nerve fiber layer will similarly disrupt axon transport mechanisms and produce accumulation of intracytoplasmic organelles at the edges of the laceration. Finally, idiopathic causes of cotton-wool spots have been described, but these cases are rare and always a diagnosis of exclusion.

Diagnostic Clues

Fortunately for the clinician, most patients who present with cotton-wool spots have other systemic or ocular findings that help narrow down their specific etiology.

It is, however, the discovery of cotton-wool spots in the otherwise healthy patient that usually brings with it considerable consternation for both the patient and the physician. Most of the etiologies described above can easily be removed from the differential diagnosis with a careful patient history, review of systems, blood-pressure measurement and ophthalmoscopic examination. Pay special attention to identifying subtle signs of hypertensive retinopathy such as A/V nicking and generalized arteriolar narrowing, or diabetic retinopathy such as aneurysmal capillary changes. Fluorescein angiography can be particularly helpful in identifying some of these changes as well as small macular branch retinal vascular occlusions.

The 'Healthy' Patient

A truly isolated cotton-wool spot in an otherwise healthy patient requires further investigation before ascribing it to idiopathic causes. First, the patient should be seen by his or her primary-care doctor for a complete history and physical examination, keeping in mind the differential diagnosis list described above. The primary-care physician should be aware of the possible etiologies associated with cotton-wool spots seen in Table 1. Again, the most common diagnosis, systemic hypertension and diabetes mellitus, warrants special attention.

Depending on the patient's cardiovascular risk factors, a more directed workup looking for cardiac valvular disease, carotid stenosis or deep venous sources of arterial emboli may be recommended. Though a complete blood count and platelet count are reasonable in most patients, a full anticoagulation workup usually is deferred in patients who do not have other clinical findings suggestive of hypercoagulable states. An erythrocyte sedimentation rate is advisable in any patient who may be at risk for temporal arteritis, regardless of the accompanying findings.

Further rheumatological testing such as antinuclear antibody titer or rheumatoid factor testing is reasonable in most patients and will help alert the physician to possible rheumatological disorders. Finally, if no underlying systemic cause for the cotton-wool spot is found, regular close follow-up of the patient is recommended to insure that no new clinical or retinal findings develop.

Dr. Arroyo is in the Retina Service at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Division of Ophthalmology, Shapiro-5th floor, 330 Brookline Ave., Boston, MA 02215. Contact him at (617) 667-3391; fax (617) 667-7092, or e-mail

[email protected].

1. Brown GC, Brown MM, Hiller T, Fischer D, Benson WE, Magargal LE. Cotton-wool spots. Retina 1985;5:206-14.

2. Arroyo JG, Irvine AR. Retinal distortion and cotton-wool spots associated with epiretinal membrane contraction. Ophthalmology 1995;102:662-8.

2. Arroyo JG, Irvine AR. Retinal distortion and cotton-wool spots associated with epiretinal membrane contraction. Ophthalmology 1995;102:662-8.