Presentation

A 27-year-old Chinese female was referred to the Wills Eye Emergency Room by an optometrist for evaluation of "papilledema." She complained of decreased vision in the left eye over the past two months. She denied any changes in the right eye.

Medical History

The patient's past ocular history was notable for myopia and amblyopia in the right eye, and an unknown eye infection in the left eye at age 3. The patient's past medial history was noncontributory. She denied having diabetes, hypertension or any other medical condition. She did not take any medicine on a regular basis. She had no known drug allergies. Family history was noncontributory. She denied smoking and the use of alcohol or intravenous drugs. Review of systems was unremarkable except for a frontal headache during the past week. She denied any numbness, tingling, weakness, meningismus or fever.

Examination

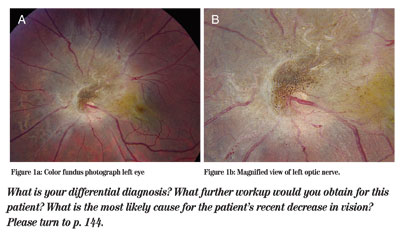

Examination revealed a spectacle corrected visual acuity of 20/400 in the right eye and 20/60 in the left eye. With pinhole, her visual acuity improved to 20/60 in the right eye and remained 20/60 in the left eye. Her pupils were pharmacologically dilated, but there was no subjective relative afferent defect and no red desaturation. Color plates were full and brisk in both eyes. Extraocular motility and confrontational visual fields were full in both eyes. Intraocular pressures by applanation tonometry were 19 mmHg in the right eye and 20 mmHg in the left eye. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy revealed quiet anterior segments bilaterally. Her dilated fundus examination was normal in the right eye. A color fundus photograph of the left eye is shown below (See Figures 1a & b).

Figure 1a (left): Color fundus photograph left eye.

Figure 1b (right): Magnified view of left optic nerve.

Diagnosis and Workup

The differential diagnosis of this pigmented juxtapapillary lesion includes a combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium, congenital simple hamartoma of the RPE, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, melanocytoma, malignant melanoma, astrocytoma, and RPE adenoma or adenocarcinoma. If the patient were a child, retinoblastoma, toxocara and persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous would also be included. In this case, the lesion is classic for a combined hamartoma of the retina and RPE.

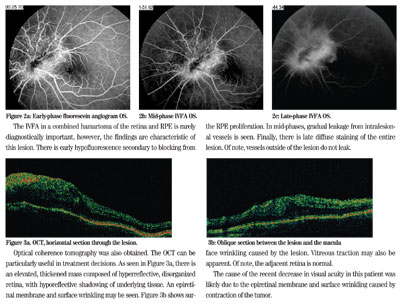

A fluorescein angiogram (IVFA) was obtained. Several images are shown below (See Figure 2).

The IVFA in a combined hamartoma of the retina and RPE is rarely diagnostically important, however, the findings are characteristic of this lesion. There is early hypofluorescence secondary to blocking from the RPE proliferation. In mid-phases, gradual leakage from intralesional vessels is seen. Finally, there is late diffuse staining of the entire lesion. Of note, vessels outside of the lesion do not leak.

Optical coherence tomography was also obtained. The OCT can be particularly useful in treatment decisions. As seen in Figure 3a, there is an elevated, thickened mass composed of hyperreflective, disorganized retina, with hyporeflective shadowing of underlying tissue. An epiretinal membrane and surface wrinkling may be seen. Figure 3b shows surface wrinkling caused by the lesion. Vitreous traction may also be apparent. Of note, the adjacent retina is normal.

Figure 2a: Early-phase fluorescein angiogram OS.

2b: Mid-phase IFVA OS.

c: Late-phase IFVA OS.

Figure 3a: OCT, horizontal section of the lesion.

b: Oblique section between the lesion and the macula.

The cause of the recent decrease in visual acuity in this patient was likely due to the epiretinal membrane and surface wrinkling caused by contraction of the tumor.

Discussion

Combined hamartoma of the retina and RPE was first described by J. Donald Gass, MD, in 1973. These congenital tumors are benign, unilateral and usually solitary. Patients with this tumor typically present in their late teenage years. Symptoms often include painless visual loss or strabismus. Acquired lesions are very rare, but have been reported following papilledema, prolonged exudative retinal detachment, and optic neuritis associated with meningoencephalitis.

Clinically, combined hamartomas of the retina and RPE are slightly elevated (80 percent) with variable pigmentation (87 percent hyperpigmented, usually black or charcoal grey). As the name implies, the lesions involve the retina and RPE. Thickened retinal and epi-retinal tissue in the central part of the lesion can cause vitreoretinal strands, though the vitreous is normally clear. Tortuous retinal vasculature within the lesion is common (90 percent). The tumors are most often juxtapapillary (76 percent), but may be macular (17 percent), or peripheral (7 percent). Contraction on the inner surface of the tumor causes displacement of the surrounding retina, which creates epiretinal membranes and may appear as retinal striae (78 percent).

These tumors do not change much over time. Growth and change in pigmentation are uncommon, but progressive distortion of the retina from contraction on the surface may cause a change in appearance. Complications resulting from this contraction include macular traction, macular holes, acquired retinoschisis, and a dragged disc in peripheral lesions. Neovascularization has been described, but is rare. Choroidal neovascular membranes may be secondary to ischemic retinal tissue peripheral to the hamartoma. Rarely, vitreous hemorrhage and exudation are seen. Of note, there is absence of direct choroidal involvement, retinal detachment and inflammation.

Combined hamartomas of the retina and RPE are most often managed by observation, since they are usually stable over time. If there is an epiretinal membrane or vitreoretinal traction present, pars plana vitrectomy with a membrane peel may be useful. This surgery is controversial, however, because if the membrane is intrinsic to the retina, peeling it could damage the nerve fiber layer or cause bleeding from traumatic peeling. In many cases, OCT may be useful to tell if vitreoretinal traction is playing a role and if there is potential plane of separation. Visual improvement postoperatively is variable as described by several case reports. In the rare case that a choroidal neovascular membrane is present, subretinal surgery, laser photocoagulation or anti-VEGF therapy may be useful.

There has been an association reported with combined hamartomas of the retina and RPE and neurofibromatosis. More commonly, they are reported with neurofibromatosis type 1, however, several case reports have described a relationship with neurofibromatosis type 2. Some advise screening patients with a combined hamartoma of the retina and RPE for neurofibromatosis. A thorough review of systems and family history should certainly be obtained.

Dr. DeCarlo is a second-year resident. She would like to thank Allen Ho, MD, who assisted with this case.