US Pharm. 2008;33(5)(Diabetes suppl):10-16.

According to the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, approximately 20.8 million people in the United

States--7% of the population--have diabetes mellitus.1

Worldwide, the World Health Organization estimates 180 million people have

diabetes, and this statistic will double by the year 2030.2

Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by

hyperglycemia, resulting from deficiencies in insulin production and/or

action. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) results from absolute insulin

deficiency and individuals require insulin via injection or pump; this

classification accounts for 5% to 10% of cases. Type 2 diabetes mellitus

(T2DM) accounts for 90% to 95% of diagnosed diabetes cases and results from

insulin resistance in which insulin is not properly utilized by the body's

cells. For most patients diagnosed with T2DM, treatment options will include

weight reduction, exercise programs, nutrition plans, and medications (i.e.,

oral medications and/or insulin therapy).3

Glycemic Control and

Clinical Evidence

Chronic

hyperglycemia can result in microvascular and macrovascular complications.

Microvascular refers to the small blood vessels and can damage the eyes,

kidneys, and nerves; whereas macrovascular refers to the larger

vessels, resulting in heart attack and/or stroke. The Diabetes Control and

Complication Trial (DCCT) and United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study

(UKPDS) concluded the benefits of attaining normal glucose concentrations in

patients with T1DM and T2DM, respectively.4-7 The DCCT demonstrated

a reduction in the development and progression of microvascular complications

by 50% to 75% among patients with T1DM.4,5 The UKPDS demonstrated a

reduction in the development of microvascular complications by 25% among

patients with T2DM.6,7

Based on the DCCT and UKPDS

trials, for every 1% decrease in glycated hemoglobin (A1C), there is a 21%

reduction in death related to diabetes and 25% to 37% reduction in

microvascular complications.4-7 In addition to long-term

complications, hyperglycemia can result in acute complications, poor wound

healing, infections, and symptoms. In order to achieve desired glycemic goals,

lifestyle modifications (i.e., weight reduction, exercise programs, nutrition

plans) and pharmacological therapy will be required. It is important for

patients to take an active role in their diabetes management by monitoring

glucose concentrations.

Self-Monitoring and

Glycemic Goals

The cornerstone of

an individual's diabetes management is glycemic control, including prevention

of hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic reactions. The two primary techniques

available for assessing glycemic control are self-monitoring of blood glucose

(SMBG) and A1C measurement. Overall, SMBG allows the patient to monitor

glycemic control on a "day-by-day" basis, while an A1C measurement is a blood

test determining the average blood glucose concentration over a two- to

three-month period.

SMBG has become the gold

standard for outpatient diabetes management and short-term assessment of

glycemic control. For most patients, it is important to obtain as many points

as possible to determine an individual's constant glycemic control, depending

upon glycemic goals and medication regimen. Self-monitoring allows for

immediate feedback to the patient and is essential to achieving glycemic goals

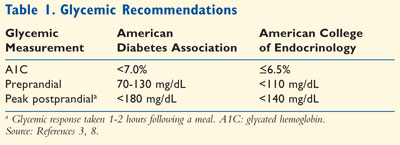

(Table 1).3,8 In addition, self-monitoring allows the

individual to play an integral role in his/her diabetes management. Health

care professionals can assess SMBG to determine if medication adjustments or

additional glycemic monitoring is necessary.

SMBG can determine if

preprandial (before a meal) or postprandial (after a meal) goals are met,

detect and prevent hypoglycemic reactions, and evaluate glycemic response to

food, physical activity, and medication changes. It is important to discuss

SMBG with all patients with either T1DM or T2DM. As a pharmacist, it is

essential to inform patients about the proper technique, interpretation of

data, and appropriate times to test glycemic response.

According to the ADA, the

following recommendations about SMBG are encouraged: 1) at least three or more

times per day among patients with T1DM, pregnant women, patients using

multiple insulin injections or insulin pump therapy; and 2) less frequently

among those on noninsulin therapy or medical nutrition therapy.3

The frequency of monitoring is determined by the needs and goals of the

patients; therefore, every patient is unique and will have a different regimen

for self-monitoring. For patients with T2DM not on insulin therapy, the

optimal frequency of SMBG is not known but should be sufficient to facilitate

reaching glucose goals.3 Certain situations may permit a patient to

monitor glycemic levels more frequently; these circumstances include

sensitivity to hypoglycemia, illness, medication changes, physical activity,

or dietary changes

Glucometers

The first blood

glucose meters (also known as glucometers) were marketed in 1971, but newer,

more sophisticated monitors have been developed. For example, the Accu-Chek

Voicemate has 20 audio features for patients with diabetes who are blind or

have visual impairment.9

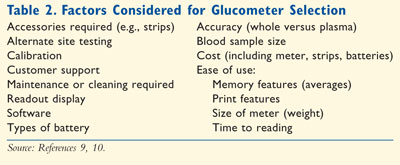

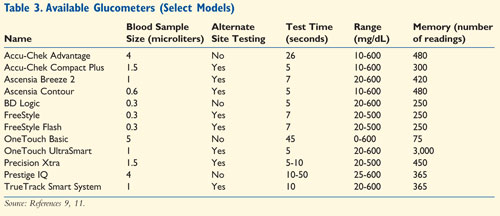

There are many factors to consider when assisting a patient in the selection of the right glucometer (Table 2 ). Depending on the retail pharmacy or store, the meter could range in price from $50 to $80.9,10 However, many manufacturers offer rebates and/or coupons. Table 3 lists some of the meters that are available in community pharmacies.9,11

Calibration

: Each glucometer has specific manufacturer's instructions for calibration

and using control solutions. For calibration, glucometers may require

insertion of a strip or chip when the monitor is purchased; other glucometers

may require proper entry of codes based on the vial of strips. If a patient

suspects erroneous readings, then a control test should be performed to verify

the glucometer and test strips. In addition, the individual should clean the

glucometer periodically. When glucometers are used properly and calibrated

corrected, glycemic results may vary by 20% in accuracy; pharmacists should

inform patients how to interpret the results.9,10 Some newer models

(e.g., Accu-Chek Compact Plus, Ascensia Breeze 2, Ascensia Contour) do not

require calibration.

Test Strips:

Test strips should be stored at room temperature in their original vial or

container. The vial should not be exposed to extreme temperatures, humidity,

or light since this improper storage may affect the accuracy. If a patient

orders the strips via a mail-order pharmacy, then the order should not be left

in the mailbox for days. The individual should check the expiration date on

the vial of strips each time a new vial is opened. In addition, it is crucial

to code the glucometer for each new vial of strips in order to get accurate

readings.

Obtaining a Blood Sample:

Obtaining a blood sample

via fingerstick may be the most difficult task for some individuals. The

patient should clean the hand with warm soapy water to increase blood

circulation. An alcohol swap can be used, but the fingertip should dry for

approximately one minute to ensure the alcohol has completely evaporated. The

lancet device is used to ensure adequate sample size and can be adjusted for

puncture depth. The lancet device should be pointed to the side of the

"tested" fingertip. Finger pads should not be punctured since this particular

area has more nerve endings and would be more painful. To increase blood flow,

the "tested" finger can be hung below the heart or massaged from the wrist up

to the tested site. Once an adequate sample is obtained, the blood should be

quickly placed on the strip.

Plasma Versus Whole

Blood: Certain

glucometer may report either plasma or whole blood (capillary) glucose

concentrations. A majority of glucometers report the glucose values as plasma

concentrations, except for the OneTouch Basic and OneTouch SureStep. Plasma

concentrations are 10% to 15% higher than whole blood glucose concentrations.

9,10

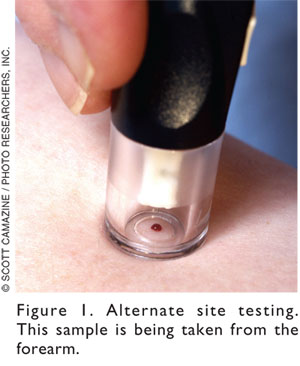

Alternate Site Testing:

Depending on the

individual's frequency of monitoring glycemic response, some patients may

complain of soreness in their fingertips and inquire about alternate site

testing. Alternate site testing (AST) is allowed at certain times and with

certain glucometers. As glucometers have become more advanced and

sophisticated, the amount of blood required has lessened. AST is less painful

due to fewer nerve endings and common sites include the palm, forearm, upper

arm, thigh, and calf (Figure 1).9,10,12 AST is reliable in a

fasting state, two hours after exercise, or two hours after meals. However,

AST locations have less capillary blood flow; therefore, these samples may not

be reflective of rapidly rising or declining glucose levels.9,10 At

any other time, the glucose levels may be rapidly fluctuating, in which

fingerstick readings would be more appropriate and reliable. When a patient

has selected a particular glucometer, it is essential to determine if the

monitor allows AST. For example, a patient can draw blood from the arm with a

OneTouch Ultra glucometer, but can check from the forearm, upper arm, thigh,

and calf with the Accu-Chek Active.9 Pharmacists have a significant

role in patient education regarding SMBG and AST.

Patient Education About

Glucometers

Pharmacists have an

integral role in educating patients about glucometers beyond calibration, test

strips, and AST. It is essential to discuss the sample size required, the time

to obtain results, memory manipulation, and replacement batteries. For

example, there are several Accu-Chek models, but each meter is not created

equal. All Accu-Chek glucometers allow AST except Accu-Chek Complete; however,

it has the largest memory capacity (i.e., holds 1,000 glucose readings) among

this manufacturer's products.9 There are many glucometers

available in community pharmacies; it is important for pharmacists in any

practice setting to remain knowledgeable about these diabetic devices.

Proper education is very

important for SMBG, especially since there are a variety of glucometers. It is

important for the patient to understand the importance of self-monitoring.

Recall demonstration by the patient would ensure understanding and allow the

pharmacist to correct any errors during this observation. Patients should be

instructed to record glucose concentrations in a logbook, with time of

medications, meals, physical activity, and any hypoglycemic reactions. This

information is valuable to the pharmacist and other health care professionals

in assessing current diabetes management and determining if a change is

necessary.

Continuous Glucose

Monitoring Systems

Over the past few

years, continuous glucose monitoring has become available as a new technology

for assessing glycemic control. The FDA has approved several continuous

glucose monitoring systems (CGMS) manufactured by Abbott Diabetes Care,

DexCom, and MiniMed; these devices continuously check interstitial glucose

concentrations throughout the day and night. CGMS does not replace the

glycemic information obtained from a standard glucometer. The CGMS has five

main components: 1) monitor, 2) glucose sensor, 3) connecting cable linking

the sensor and monitor, 4) docking station, and 5) test plug.13,14

The monitor resembles a pager

and collects the glucose information from the sensor. This component can be

attached to the patient's belt or waistline. The patient must calibrate the

monitor three to four times a day by performing fingersticks with a standard

glucometer taken at different times of the day. Special events (i.e.,

medication taken, exercise performed, or meals consumed) should be noted. For

showering, the patient may place a ShowerPak (a specially designed plastic

bag) over the monitor to prevent water damage as it is not waterproof. The

sensor consists of glucose-sensing electrodes on a polyurethane tube and rigid

introducer needle.14 The needle is inserted approximately 5

millimeters underneath the skin of the abdomen.14 The insertion of

the glucose sensor is quick and relatively painless. It is important to keep

the site of insertion sterile and the adhesive patch firmly placed to prevent

the sensor from moving. Depending on the manufacturer, measurements are

averaged every five minutes; this glucose information will be transmitted to

the monitor wirelessly.

After the glucose information

is collected (usually every three days), the sensor will be removed and the

information from the monitor will be downloaded into a computer. The monitor

is placed on a docking stand and downloaded on a standard computer using the

programmed software. A variety of graphs and charts can be printed, revealing

patterns of glucose fluctuations.

The main advantage of using

CGMS is to identify fluctuations and trends; for example, it can capture

unnoticed hypoglycemic reactions or episodes or elevated postprandial readings

in an individual. In addition, the pharmacist and other health care

professionals would be able to assess glucose concentrations in response to

dietary habits, exercise, and medications and make any necessary adjustments.

One study demonstrated the

advantage of using CGMS among patients with T1DM in detecting unrecognized

hypoglycemia.15 According to the ADA, CGMS serves as a supplemental

tool for detecting hypoglycemia unawareness, but there are no controlled

trials demonstrating improved long-term glycemic control.3 Poor

reimbursement has been the greatest barrier of the CGMS. Payers are reluctant

to provide reimbursement for patients while covering providers' time for

device application and education.13 Some insurance companies may

provide coverage or reimbursement, but certain criteria have to be met such as

unrecognized hypoglycemic reactions or suspected postprandial concentrations

with elevated A1C and normal fasting glucose concentrations.13

Continuous glucose monitoring can be reimbursed by Medicare and may be covered

by private insurance plans; inform patients to check with their insurance

carrier.

Conclusion

The prevalence of

diabetes mellitus continues to rise and is projected to increase over the next

several decades. There are a variety of agents available to health care

professional for diabetes management; it poses a challenge to pharmacists in

selecting and adjusting an individual's therapy in order to achieve short and

long-term glycemic levels. The cornerstone to diabetes management is glycemic

control. Pharmacists play an integral role in patient education regarding

glucometers. Returning to the basics by providing education about glycemic

goals, glucometers, self-monitoring techniques, and CGMS is very

important.

REFERENCES

1. Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National diabetes fact sheet: general

information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2005.

Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2005.

2. World Health Organization. Diabetes fact sheet. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/index.html. Accessed February 21, 2008.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;30(suppl 1):S12-S54.

4. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977-986.

5. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes four years after a trial of intensive therapy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:381-389.

6. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet. 1998;352:854-865.

7. UKPDS 33. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 1998;352:837-853.

8. American College of Endocrinologists. Medical guidelines for clinical practice for management of diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2007;13(suppl 1):1-66.

9. Assemi M, Morello CM. Chapter 47: Diabetes mellitus. In: Berardi RR, McDermott JH, Newton GD, et al, eds. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs: An Interactive Approach to Self-Care. 15th ed. Washington, DC: APhA; 2006.

10. O'Mara NM. Blood glucose meters. Pharmacist's/Prescriber's Letter. 2005;21:211208.

11. 2008 resource guide. Blood glucose monitoring and data management systems. Diabetes Forecast. 2008;61:RG31-RG48. www.diabetes.org/uedocuments/df-rg-monitors-0108.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2008.

12. Alternate site testing. www.abbottdiabetescare.com/static/content/image/asta_figure.gif. Accessed February 7, 2008.

13. Klonoff DC. A review of continuous glucose monitoring technology. Diabetes Technol Thera. 2005;7:770-775.

14. FDA. Continuous glucose monitoring system. www.fda.gov. Accessed February 20, 2008.

15. Chico A, Rio-Vidal P, Subira M,

Novials A. The continuous glucose monitoring system is useful for detecting

unrecognized hypoglycemias in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes but is

not better than frequent capillary glucose measurements for improving

metabolic control. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1153-1157.

To comment on this article,

contact [email protected].